JDN 2457180 EDT 08:49

Welcome to the second installment in my series, “Top 10 Things to Know About Economics.” The first was not all that well-received, because it turns it out it was just too dense with equations (it didn’t help that the equation formatting was a pain.) Fortunately I think I can explain monopoly and oligopoly with far fewer equations—which I will represent as PNG for your convenience.

You probably already know at least in basic terms how a monopoly works: When there is only one seller of a product, that seller can charge higher prices. But did you ever stop and think about why they can charge higher prices—or why they’d want to?

The latter question is not as trivial as it sounds; higher prices don’t necessarily mean higher profits. By the Law of Demand (which, like the Pirate Code, is really more like a guideline), raising the price of a product will result in fewer being sold. There are two countervailing effects: Raising the price raises the profits from selling each item, but reduces the number of items sold. The optimal price, therefore, is the one that balances these two effects, maximizing price times quantity.

A monopoly can actually set this optimal price (provided that they can figure out what it is, of course; but let’s assume they can). They therefore solve this maximization problem for price P(Q) a function of quantity sold, quantity Q, and cost C(Q) a function of quantity produced (which at the optimum is equal to quantity sold; no sense making them if you won’t sell them!):

As you may remember if you’ve studied calculus, the maximum is achieved at the point where the derivative is zero. If you haven’t studied calculus, the basic intuition here is that you move along the curve seeing whether the profits go up or down with each small change, and when you reach the very top—the maximum—you’ll be at a point where you switch from going up to going down, and at that exact point a small change will move neither up nor down. The derivative is really just a fancy term for the slope of the curve at each point; at a maximum this slope changes from positive to negative, and at the exact point it is zero.

This is a general solution, but it’s easier to understand if we use something more specific. As usual, let’s make things simpler by assuming everything is linear; we’ll assume that demand starts at a maximum price of P0 and then decreases at a rate 1/e. This is the demand curve.

Then, we’ll assume that the marginal cost of production C'(Q) is also linear, increasing at a rate 1/n. This is the supply curve.

Now we can graph the supply and demand curves from these equations. But the monopoly doesn’t simply set supply equal to demand; instead, they set supply equal to marginal revenue, which takes into account the fact that selling more items requires lowering the price on all of them. Marginal revenue is this term:

This is strictly less than the actual price, because increasing the quantity sold requires decreasing the price—which means that P'(Q) < 0. They set the quantity by setting marginal revenue equal to marginal cost. Then they set the price by substituting that quantity back into the demand equation.

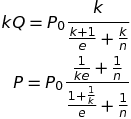

Thus, the monopoly should set this quantity:

They would then charge this price (substitute back into the demand equation):

On a graph, there are the supply and demand curves, and then below the demand curve, the marginal revenue curve; it’s the intersection of that curve with the supply curve that the monopoly uses to set its quantity, and then it substitutes that quantity into the demand curve to get the price:

Now I’ll show that this is higher than the price in a perfectly competitive market. In a competitive market, competitive companies can’t do anything to change the price, so from their perspective P'(Q) = 0. They can only control the quantity they produce and sell; they keep producing more as long as they receive more money for each one than it cost to produce it. By the Law of Diminishing Returns (again more like a guideline) the cost will increase as they produce more, until finally the last one they sell cost just as much to make as they made from selling it. (Why bother selling that last one, you ask? You’re right; they’d actually sell one less than this, but if we assume that we’re talking about thousands of products sold, one shouldn’t make much difference.)

Price is simply equal to marginal cost:

In our specific linear case that comes out to this quantity:

Therefore, they charge this price (you can substitute into either the supply or demand equations, because in a competitive market supply equals demand):

Subtract the two, and you can see that monopoly price is higher than the competitive price by this amount:

Notice that the monopoly price will always be larger than the competitive price, so long as e > 0 and n > 0, meaning that increasing the quantity sold requires decreasing the price, but increasing the cost of production. A monopoly has an incentive to raise the price higher than the competitive price, but not too much higher—they still want to make sure they sell enough products.

Monopolies introduce deadweight loss, because in order to hold the price up they don’t produce as many products as people actually want. More precisely, each new product produced would add overall value to the economy, but the monopoly stops producing them anyway because it wouldn’t add to their own profits.

One “solution” to this problem is to let the monopoly actually take those profits; they can do this if they price-discriminate, charging a higher price for some customers than others. In the best-case scenario (for them), they charge each customer a price that they are just barely willing to pay, and thus produce until no customer is willing to pay more than the product costs to make. That final product sold also has price equal to marginal cost, so the total quantity sold is the same under competition. It is, in that sense, “efficient”.

What many neoclassical economists seem to forget about price-discriminating monopolies is that they appropriate the entire surplus value of the product—the customers are only just barely willing to buy; they get no surplus value from doing so.

In reality, very few monopolies can price-discriminate that precisely; instead, they put customers into broad categories and then try to optimize the price for each of those categories. Credit ratings, student discounts, veteran discounts, even happy hours are all forms of this categorical price discrimination. If the company cares even a little bit about what sort of customer you are rather than how much money you’re paying, they are price-discriminating.

It’s so ubiquitous I’m actually having trouble finding a good example of a product that doesn’t have categorical price discrimination. I was thinking maybe computers? Nope, student discounts. Cars? No, employee discounts and credit ratings. Refrigerators, maybe? Well, unless there are coupons (coupons price discriminate against people who don’t want to bother clipping them). Certainly not cocktails (happy hour) or haircuts (discrimination by sex, the audacity!); and don’t even get me started on software.

I introduced price-discrimination in the context of monopoly, which is usually how it’s done; but one thing you’ll notice about all the markets I just indicated is that they aren’t monopolies, yet they still exhibit price discrimination. Cars, computers, refrigerators, and software are made under oligopoly, a system in which a handful of companies control the majority of the market. As you might imagine, an oligopoly tends to act somewhere in between a monopoly and a competitive market—but there are some very interesting wrinkles I’ll get to in a moment.

Cocktails and haircuts are sold in a different but still quite interesting system called monopolistic competition; indeed, I’m not convinced that there is any other form of competition in the real world. True perfectly-competitive markets just don’t seem to actually exist. Under monopolistic competition, there are many companies that don’t have much control over price in the overall market, but the products they sell aren’t quite the same—they’re close, but not equivalent. Some barbers are just better at cutting hair, and some bars are more fun than others. More importantly, they aren’t the same for everyone. They have different customer bases, which may overlap but still aren’t the same. You don’t just want a barber who is good, you want one who works close to where you live. You don’t just want a bar that’s fun; you want one that you can stop by after work. Even if you are quite discerning and sensitive to price, you’re not going to drive from Ann Arbor to Cleveland to get your hair cut—it would cost more for the gasoline than the difference. And someone is Cleveland isn’t going to drive all the way to Ann Arbor, either! Hence, barbers in Ann Arbor have something like a monopoly (or oligopoly) over Ann Arbor haircuts, and barbers in Cleveland have something like a monopoly over Cleveland haircuts. That’s monopolistic competition.

Supposedly monopolistic competition drives profits to zero in the long run, but I’ve yet to see this happen in any real market. Maybe the problem is that conceit “the long run”; as Keynes said, “in the long run we are all dead.” Sometimes the argument is made that it has driven real economic profits to zero, because you’ve got to take into account the cost of entry, the normal profit. But of course, that’s extremely difficult to measure, so how do we know whether profits have been driven to normal profit? Moreover, the cost of entry isn’t the same for everyone, so people with lower cost of entry are still going to make real economic profits. This means that the majority of companies are going to still make some real economic profit, and only the ones that had the hardest time entering will actually see their profits driven to zero.

Monopolistic competition is relatively simple. Oligopoly, on the other hand, is fiercely complicated. Why? Because under oligopoly, you actually have to treat human beings as human beings.

What I mean by that is that under perfect competition or even monopolistic competition, the economic incentives are so powerful that people basically have to behave according to the neoclassical rational agent model, or they’re going to go out of business. There is very little room for errors or even altruistic acts, because your profit margin is so tight. In perfect competition, there is literally zero room; in monopolistic competition, the only room for individual behavior is provided by the degree of monopoly, which in most industries is fairly small. One person’s actions are unable to shift the direction of the overall market, so the market as a system has ultimate power.

Under oligopoly, on the other hand, there are a handful of companies, and people know their names. You as a CEO have a reputation with customers—and perhaps more importantly, a reputation with other companies. Individual decision-makers matter, and one person’s decision depends on their prediction of other people’s decision. That means we need game theory.

The simplest case is that of duopoly, where there are only two major companies. Not many industries are like this, but I can think of three: soft drinks (Coke and Pepsi), commercial airliners (Boeing and Airbus), and home-user operating systems (Microsoft and Apple). In all three cases, there is also some monopolistic element, because the products they sell are not exactly the same; but for now let’s ignore that and suppose they are close enough that nobody cares.

Imagine yourself in the position of, say, Boeing: How much should you charge for an airplane?

If Airbus didn’t exist, it’s simple; you’d charge the monopoly price. But since they do exist, the price you charge must depend not only on the conditions of the market, but also what you think Airbus is likely to do—and what they are likely to do depends in turn on what they think you are likely to do.

If you think Airbus is going to charge the monopoly price, what should you do? You could charge the monopoly price as well, which is called collusion. It’s illegal to actually sign a contract with Airbus to charge that price (though this doesn’t seem to stop cable companies or banks—probably has something to do with the fact that we never punish them for doing it), and let’s suppose you as the CEO of Boeing are an honest and law-abiding citizen (I know, it’s pretty fanciful; I’m having trouble keeping a straight face myself) and aren’t going to violate the antitrust laws. You can still engage in tacit collusion, in which you both charge the monopoly price and take your half of the very high monopoly profits.

There’s a temptation not to collude, however, which the airlines who buy your planes are very much hoping you’ll succumb to. Suppose Airbus is selling their A350-100 for $341 million. You could sell the comparable 777-300ER for $330 million and basically collude, or you could cut the price and draw in more buyers. Say you cut it to $250 million; it probably only costs $150 million to make, so you’re still making a profit on each one; but where you sold say 150 planes a year and profited $180 million on each (a total profit of $27 billion), you could instead capture the whole market and sell 300 planes a year and profit $100 million on each (a total profit of $30 billion). That’s a 10% higher profit and $3 billion a year for your shareholders; why wouldn’t you do that?

Well, think about what will happen when Airbus releases next year’s price list. You cut the price to $250 million, so they retaliate by cutting their price to $200 million. Next thing you know, you’re cutting your own price to $150.1 million just to stay in the market, and they’re doing the same. When the dust settles, you still only control half the market, but now you profit a mere $100,000 per airplane, making your total profits a measly $15 million instead of $27 billion—that’s $27,000 million. (I looked it up, and as it turns out, Boeing’s actual gross profit is about $14 billion, so I underestimated the real cost of each airplane—but they’re clearly still colluding.) For a gain of 10% in one year you’ve paid a loss of 99.95% indefinitely. The airlines will be thrilled, and they’ll likely pass on much of those savings to their customers, who will fly more often, engage in more tourism, and improve the economy in tourism-dependent countries like France and Greece, so the world may well be better off. But you as CEO of Boeing don’t care about the world; you care about the shareholders of Boeing—and the shareholders of Boeing just got hosed. Don’t expect to keep your seat in the next election.

But now, suppose you think that Airbus is planning on setting a price of $250 million next year anyway. They should know you’ll retaliate, but maybe their current CEO is retiring next year and doesn’t care what happens to the company after that or something. Or maybe they’re just stupid or reckless. In any case, your sources (which, as an upstanding citizen, obviously wouldn’t include any industrial espionage!) tell you that Airbus is going to charge $250 million next year.

Well, in that case there’s no point in you charging $330 million; you’ll lose the market and look like a sucker. You could drop to $250 million and try to set up a new, lower collusive equilibrium; but really what you want to do is punish them severely for backstabbing you. (After all, human beings are particularly quick to anger when we perceive betrayal. So maybe you’ll charge $200 million and beat them at their own conniving game.

The next year, Airbus has a choice. They could raise back to $341 million and give you another year of big profits to atone for their reckless actions, or they could cut down to $180 million and keep the price war going. You might think that they should continue the war, but that’s short-term thinking; in the long run their best strategy is to atone for their actions and work to restore the collusion. In response, Boeing’s best strategy is to punish them when they break the collusion, but not hold a grudge; if they go back to the high price, Boeing should as well. This very simple strategy is called tit-for-tat, and it is utterly dominant in every simulation we’ve ever tried of this situation, which is technically called an iterated prisoner’s dilemma.

What if there are more than two companies involved? Then things get even more complicated, because now we’re dealing with things like what A’s prediction of what B predicts that C will predict A will do. In general this is a situation we only barely understand, and I think it is a topic that needs considerably more research than it has received.

There is an interesting simple model that actually seems to capture a lot about how oligopolies work, but no one can quite figure out why it works. That model is called Cournot competition. It assumes that companies take prices and fixed and compete by selecting the quantity they produce at each cycle. That’s incredibly bizarre; it seems much more realistic to say that they compete by setting prices. But if you do that, you get Bertrand competition, which requires us to go through that whole game-theory analysis—but now with three, or four, or ten companies!

Under Cournot competition, you decide how much to produce Q1 by monopolizing what’s left over after the other companies have produced their quantities Q2, Q3, and so on. If there are k companies, you optimize under the constraint that (k-1)Q2 has already been produced.

Let’s use our linear models again. Here, the quantity that goes into figuring the price is the total quantity, which is Q1+(k-1)Q2; while the quantity you sell is just Q1. But then, another weird part is that for the marginal cost function we use the whole market—maybe you’re limited by some natural resource, like oil or lithium?

It’s not as important for you to follow along with the algebra, though here you go if you want:

Then the key point is that the situation is symmetric, so Q1 = Q2 = Q3 = Q. Then the total quantity produced, which is what consumers care about, is kQ. That’s what sets the actual price as well.

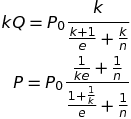

The two equations to focus on are these ones:

If you plug in k=1, you get a monopoly. If you take the limit as k approaches infinity, you get perfect competition. And in between, you actually get a fairly accurate representation of how the number of companies in an industry affects the price and quantity sold! From some really bizarre assumptions about how competition works! The best explanation I’ve seen of why this might happen is this 1983 paper showing that price competition can behave like Cournot competition if companies have to first commit to producing a certain quantity before naming their prices.

But of course, it doesn’t always give an accurate representation of oligopoly, and for that we’ll probably need a much more sophisticated multiplayer game theory analysis which has yet to be done.

And that, dear readers, is how monopoly and oligopoly raise prices.