The housing affordability crisis in one graph

Mar 8 JDN 2461108

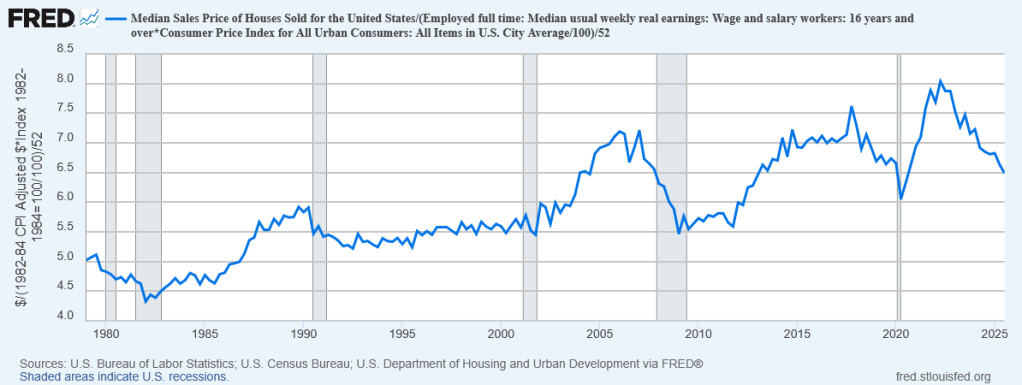

The graph below, constructed from FRED data, provides a simple measure of housing affordability: How many years of median earnings does it take to afford the median home?

From a low of 4.4 in 1982, this rose to about 5.5 and was relatively stable in the 1990s. Then in the 2000s, it began to rise, peaked at 7.2 just before the housing crisis, and then rapidly dropped to back to 5.5 again.

Then in the 2010s it began to rise again, peaked even higher at 7.6 in 2017, and then dropped down to 6.0 in 2020 before beginning to rise anew. In 2023 it reached a yet higher peak of 8.0, and then has been slowly declining ever since—but is still about 6.5, well above its 1990s level.

I honestly expected worse than this, but I think part of what’s happening is that new homes have gotten a bit smaller in the past few years: median square footage of homes sold has fallen from a peak of 1997 in 2019 to 1788 today. (Unfortunately, FRED doesn’t have this data series going back any earlier than 2016.)

If we adjust for that, the price a typical 2019 home today would be about 7.2 years of median earnings, which is about what it was at the peak of the housing crisis in 2007.

Note of course this isn’t actually how many years you need to save up to buy a house. You clearly can’t save your entire earnings, but you also don’t need to come up with the full price, only the down payment. And what you can afford also depends upon interest rates and such. But still, it’s a pretty clear sign that housing is radically more expensive now than it was in the 1980s or even 1990s.

In my view, this is the affordability crisis.

Gas prices really aren’t that important. Car prices are relatively stable. Food prices are volatile but don’t have a bad long-term trend. We do still have serious problems with affordability in education and healthcare, but we have obvious solutions available (that several other countries are already doing successfully); we’re just not doing them because Republicans don’t like them. But housing? We have no clear solutions on the table, certainly not anything that would be politically viable. Fundamentally, we need to build more housing in places people want to live—a lot more housing—and force the price of housing down.

And with our society structured the way it is, when you price people out of housing, you price them out of adulthood. Millennials are not having kids at anywhere near the rate of previous generations, because raising kids requires living space. Especially with immigration collapsing after Trump, this housing affordability crisis is going to turn into a population crisis.

I guess what I’m hoping for at the moment is just consciousness-raising, making people see that this is actually a problem. For some reason, everyone agrees that rising prices of goods are a bad thing, except when it comes to housing.

Inflation in food? An urgent crisis that must be immediately resolved.

Inflation in gas prices? So terrible it’s worth invading other countries over.

Inflation in housing? No, somehow that’s good actually, because it makes homeowners feel richer (even though they actually owe more in property taxes). We treat housing like an asset instead of a good, which is something we should absolutely never, ever do with a good that people need to live.