JDN 2456984 PST 12:20.

The deficit! It’s big and scary! And our national debt is rising by the second, says a “debt clock” that is literally just linearly extrapolating the trend. You don’t actually think that there are economists marking down every single dollar the government spends and uploading it immediately, do you? We’ve got better things to do. Conservatives will froth at the mouth over how Obama is the “biggest government spender in world history“, which is true if you just look at the dollar amounts, but of course it is; Obama is the president of the richest country in world history. If the government continues to tax at the same rate and spend what it taxes, government spending will be a constant proportion of GDP (which isn’t quite true, but it’s pretty close; there are ups and downs but for the last 40 years or so federal spending is generally in the range 30% to 35% of GDP), and the GDP of the United States is huge, and far beyond that of any other nation not only today, but ever. This is particularly true if you use nominal dollars, but it’s even true if you use inflation-adjusted real GDP. No other nation even gets close to US GDP, which is about to reach $17 trillion a year (unless you count the whole European Union as a nation, in which case it’s a dead heat).

China recently passed us if you use purchasing-power-parity, but that really doesn’t mean much, because purchasing-power-parity, or PPP, is a measure of standard of living, not a measure of a nation’s total economic power. If you want to know how well people in a country live, you use GDP per capita (that is, per person) PPP. But if you want to know a country’s capacity to influence the world economy, what matters is so-called real GDP, which is adjusted for inflation and international exchange rates. The difference is that PPP will tell you how many apples a person can buy, but real GDP will tell you how many aircraft carriers a government can build. The US is still doing quite well in that department, thank you; we have 10 of the world’s 20 active aircraft carriers, which is to say as many as everyone else combined. The US has 4% of the world’s population and 24% of the world’s economic output.

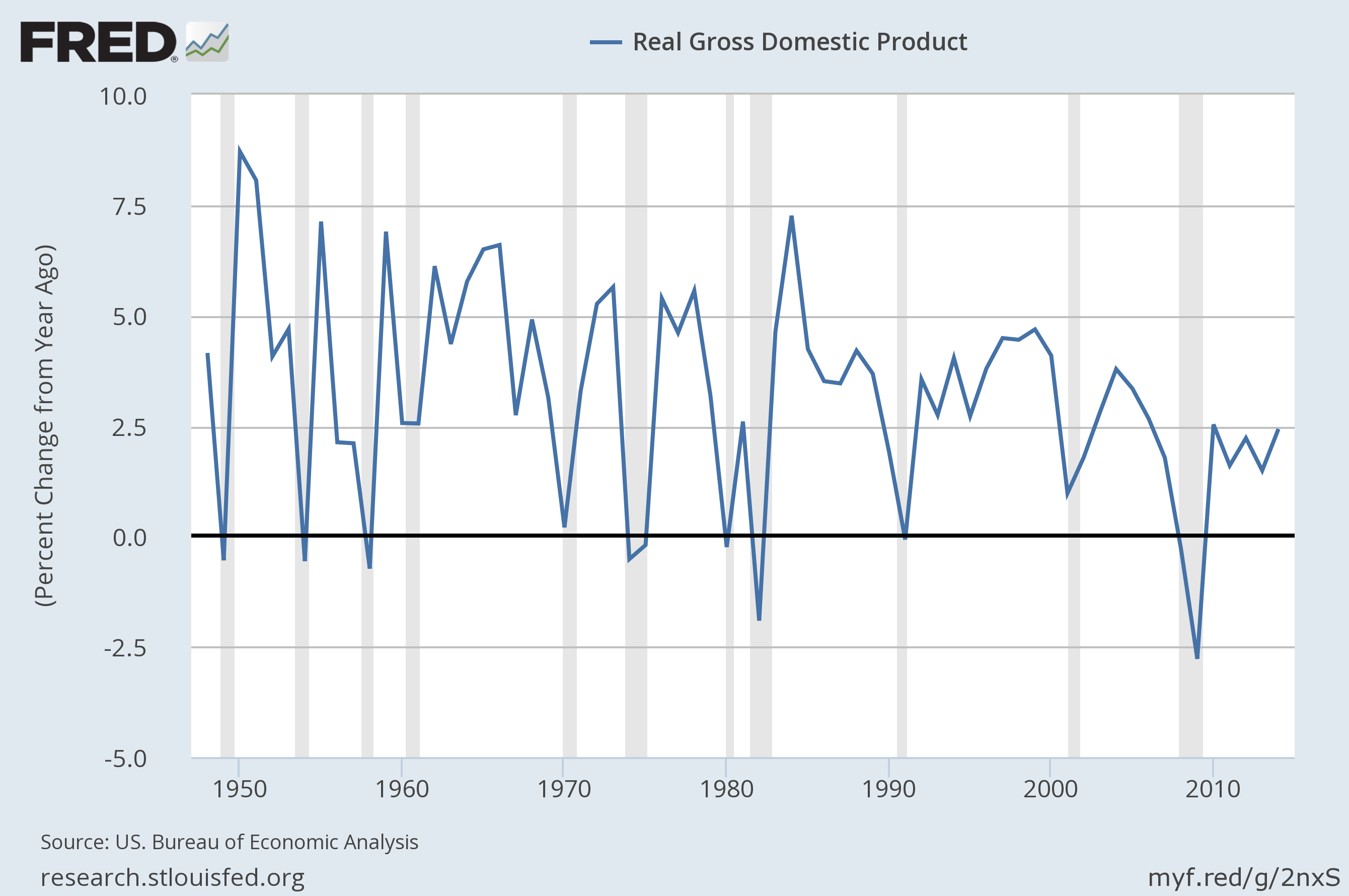

In particular, GDP in the US has been growing rather steadily since the Great Recession, and we are now almost recovered from the Second Depression and back to our equilibrium level of unemployment and economic growth. As the economy grows, government spending grows alongside it. Obama has actually presided over a decrease in the proportion of government spending relative to GDP, largely because of all this political pressure to reduce the deficit and stop the growth of the national debt. Under Obama the deficit has dropped dramatically.

But what is the deficit, anyway? And how can the deficit be decreasing if the debt clock keeps ticking up?

The government deficit is simply the difference between total government spending and total government revenue. If the government spends $3.90 trillion and takes in $3.30 trillion, the deficit is going to be $0.60 trillion, or $600 billion. In the rare case that you take in more than you spend, the deficit would be negative; we call that a surplus instead. (This almost never happens.)

Because of the way the US government is financed, the deficit corresponds directly to the national debt, which is the sum of all outstanding loans to the government. Every time the government spends more than it takes in, it makes up the difference by taking out a loan, in the form of a Treasury bond. As long as the deficit is larger than zero, the debt will increase. Think of the debt as where you are, and the deficit as how fast you’re going; you can be slowing down, but you’ll continue to move forward as long as you have some forward momentum.

Who is giving us these loans? You can look at the distribution of bondholders here. About a third of the debt is owned by the federal government itself, which makes it a very bizarre notion of “debt” indeed. Of the rest, 21% is owned by states or the Federal Reserve, so that’s also a pretty weird kind of debt. Only 55% of the total debt is owned by the public, and of those 39% are people and corporations within the United States. That means that only 33% of the national debt is actually owned by foreign people, corporations, or governments. What we actually owe to China is about $1.4 trillion. That’s a lot of money (it’s literally enough to make an endowment that would end world hunger forever), but our total debt is almost $18 trillion, so that’s only 8%.

When most people see these huge figures they panic: “Oh my god, we owe $18 trillion! How will we ever repay that!” Well, first of all, our GDP is $17 trillion, so we only owe a little over one year of income. (I wish I only owed one year of income in student loans….)

But in fact we don’t really owe it at all, and we don’t need to ever repay it. Chop off everything that’s owned by US government institutions (including the Federal Reserve, which is only “quasi-governmental”), and the figure drops down to $9.9 trillion. If by we you mean American individuals and corporations, then obviously we don’t owe back the debt that’s owned by ourselves, so take that off; now you’re looking at $6 trillion. That’s only about 4 months of total US economic output, or less than two years of government revenue.

And it gets better! The government doesn’t need to somehow come up with that money; they don’t even have to raise it in taxes. They can print that money, because the US government has a sovereign currency and the authority to print as much as we want. Really, we have the sovereign currency, because the US dollar is the international reserve currency, the currency that other nations hold in order to make exchanges in foreign markets. Other countries buy our money because it’s a better store of value than their own. Much better, in fact; the US has the most stable inflation rate in the world, and has literally never undergone hyperinflation. Better yet, the last time we had prolonged deflation was the Great Depression. This system is self-perpetuating, because being the international reserve currency also stabilizes the value of your money.

This is why it’s so aggravating to me when people say things like “the government can’t afford that” or “the government is broke” or “that money needs to come from somewhere”. No, the government can’t be broke! No, the money doesn’t have to come from somewhere! The US government is the somewhere from which the world’s money comes. If there is one institution in the world that can never, ever be broke, it is the US government. This gives our government an incredible amount of power—combine that with our aforementioned enormous GDP and fleet of aircraft carriers, and you begin to see why the US is considered a global hegemon.

To be clear: I’m not suggesting we eliminate all taxes and just start printing money to pay for everything. Taxes are useful, and we should continue to have them—ideally we would make them more progressive than they presently are. But it’s important to understand why taxes are useful; it’s really not that they are “paying for” government services. It’s actually more that they are controlling the money supply. The government creates money by spending, then removes money by taxing; in this way we maintain a stable growth of the money supply that allows us to keep the economy running smoothly and maintain inflation at a comfortable level. Taxes also allow the government to redistribute income from those who have it and save it to those who need it and will spend it—which is all the more reason for them to be progressive. But in theory we could eliminate all taxes without eliminating government services; it’s just that this would cause a surge in inflation. It’s a bad idea, but by no means impossible.

When we have a deficit, the national debt increases. This is not a bad thing. This is a fundamental misconception that I hope to disabuse you of: Government debt is not like household debt or corporate debt. When people say things like “we need to stop spending outside our means” or “we shouldn’t put wars on the credit card”, they are displaying a fundamental misunderstanding of what government debt is. The government simply does not operate under the same kind of credit constraints as you and I.

First, the government controls its own interest rates, and they are always very low—typically the lowest in the entire economy. That already gives it a lot more power over its debt than you or I have over our own.

Second, the government has no reason to default, because they can always print more money. That’s probably why bondholders tolerate the fact that the government sets its own interest rates; sure, it only pays 0.5%, but it definitely pays that 0.5%.

Third, government debt plays a role in the functioning of global markets; one of the reasons why China is buying up so much of our debt is so that they can keep the dollar high in value and thus maintain their trade surplus. (This is why whenever someone says something like, “The government needs to stop going further into debt, just like how I tightened my belt and paid off my mortgage!” I generally reply, “So when was the last time someone bought your debt in order to prop up your currency?”) This is also why we can’t get rid of our trade deficit and maintain a “strong dollar” at the same time; anyone who wants to do that may feel patriotic, but they are literally talking nonsense. The stronger the dollar, the higher the trade deficit.

Fourth, as I already hinted at above, the government doesn’t actually need debt at all. Government debt, like taxation, is not actually a source of funding; it is a tool of monetary policy. (If you’re going to quote one sentence from this post, it should be the previous; that basically sums up what I’m saying.) Even without raising taxes or cutting spending, the government could choose not to issue bonds, and instead print cash. You could make a sophisticated economic argument for how this is really somehow “issuing debt with indefinite maturity at 0% interest”; okay, fine. But it’s not what most people think of when they think of debt. (In fact, sophisticated economic arguments can go quite the opposite way: there’s a professor at Harvard I may end up working with—if I get into Harvard for my PhD of course—who argues that the federal debt and deficit are literally meaningless because they can be set arbitrarily by policy. I think he goes too far, but I see his point.) This is why many economists were suggesting that in order to get around ridiculous debt-ceiling intransigence Obama could simply Mint the Coin.

Government bonds aren’t really for the benefit of the government, they’re for the benefit of society. They allow the government to ensure that there is always a perfectly safe investment that people can buy into which will anchor interest rates for the rest of the economy. If we ever did actually pay off all the Treasury bonds, the consequences could be disastrous.

Fifth, the government does not have a credit limit; they can always issue more debt (unless Congress is filled with idiots who won’t raise the debt ceiling!). The US government is the closest example in the world to what neoclassical economists call a perfect credit market. A perfect credit market is like an ideal rational agent; these sort of things only exist in an imaginary world of infinite identical psychopaths. A perfect credit market would have perfect information, zero transaction cost, zero default risk, and an unlimited quantity of debt; with no effort at all you could take out as much debt as you want and everyone would know that you are always guaranteed to pay it back. This is in most cases an utterly absurd notion—but in the case of the US government it’s actually pretty close.

Okay, now that I’ve deluged you with reasons why the national debt is fundamentally different from a household mortgage or corporate bond, let’s get back to talking about the deficit. As I mentioned earlier, the deficit is almost always positive; the government is almost always spending more money than it takes in. Most people think that is a bad thing; it is not.

It would be bad for a corporation to always run a deficit, because then it would never make a profit. But the government is not a for-profit corporation. It would be bad for an individual to always run a deficit, because eventually they would go bankrupt. But the government is not an individual.

In fact, the government running a deficit is necessary for both corporations to make profits and individuals to gain net wealth! The government is the reason why our monetary system is nonzero-sum.

This is actually so easy to see that most people who learn about it react with shock, assuming that it can’t be right. There can’t be some simple and uncontroversial equation that shows that government deficits are necessary for profits and savings. Actually, there is; and the fact that we don’t talk about this more should tell you something about the level of sophistication in our economic discourse.

Individuals do work, get paid wages W. (This also includes salaries and bonuses; it’s all forms of labor income.) They also get paid by government spending, G, and pay taxes, T. Let’s pretend that all taxing and spending goes to people and not corporations. This is pretty close to true, especially since corporations as big as Boeing frequently pay nothing in taxes. Corporate subsidies, while ridiculous, are also a small portion of spending—no credible estimate is above $300 billion a year, or less than 10% of the budget. (Without that assumption the equation has a couple more terms, but the basic argument doesn’t change.) People use their money to buy consumption goods, C. What they don’t spend they save, S.

S = (W + G – T) – C

I’m going to rearrange this for reasons that will soon become clear:

S = (W – C) + (G – T)

I’ll also subtract investment I from both sides, again for reasons that will become clear:

S – I = (W – C – I) + (G – T)

Corporations hire workers and pay them W. They make consumption goods which are then sold for C. They also sell to foreign companies and buy from foreign companies, exporting X and importing M. Since we have a trade deficit, this means that X < M. Finally, they receive investment I that comes in the form of banks creating money through loans (yes, banks can create money). Most of our monetary policy is in the form of trying to get banks to create more money by changing interest rates. Only when desperate do we actually create the money directly (I’m not sure why we do it this way). In any case, this yields a total net profit P.

P = C + I – W + (X – M)

Now, if the economy is functioning well, we want profits and savings to both be positive—both people and corporations will have more money on average next year then they had this year. This means that S > 0 and P > 0. We also don’t want the banks loaning out more money than people save—otherwise people go ever further into debt—so we actually want S > I, or S – I > 0. If S – I > 0, people are paying down their debts and gaining net wealth. If S – I < 0, people are going further into debt and losing net wealth. In a well-functioning economy we want people to be gaining net wealth.

In order to have P > 0, because X – M < 0 we need to have C + I > W. People have to spend more on consumption and investment than they are paid in wages—have to, absolutely have to, as a mathematical law—in order for corporations to make a profit.

But then if C + I > W, W – C – I < 0, which means that the first term of the savings equation is negative. In order for savings to be positive, it must be—again as a mathematical law—that G – T > 0, which means that government spending exceeds taxes. In order for both corporations to profit and individuals to save at the same time, the government must run a deficit.

There is one other way, actually, and that’s for X – M to be positive, meaning you run a trade surplus. But right now we don’t, and moreover, the world as a whole necessarily cannot. For the world as a whole, X = M. This will remain true at least until we colonize other planets. This means that in order for both corporate profits and individual savings to be positive worldwide, overall governments worldwide must spend more than they take in. It has to be that way, otherwise the equations simply don’t balance.

You can also look at it another way by adding the equations for S – I and P:

S – I + P = (G – T) + (X – M)

Finally, you can also derive this a third way. This is your total GDP which we usually call Y (“yield”, I think?); it’s equal to consumption plus investment plus government spending, plus net exports:

Y = C + I + G + (X – M)

It’s also equal to consumption plus profit plus saving plus taxes:

Y = C + P + S + T

So those two things must be the same:

C + S + T + P = C + I + G + (X – M)

Canceling and rearranging we get:

(S – I) + P = (G – T) + (X – M)

The sum of saving minus investment (which we can sort of think of as “net saving”) plus profit is equal to the sum of the government deficit and the trade surplus. (Usually you don’t see P in this sectoral balances equation because no distinction is made between consumers and corporations and P is absorbed into S.)

From the profit equation:

W = C + I + (X – M) – P

Put that back into our GDP equation:

Y = W + P + G

GDP is wages plus profits plus government spending.

That’s a lot of equations; simple equations, but yes, equations. Lots of people are scared by equations. So here, let me try to boil it down to a verbal argument. When people save and corporations make profits, money gets taken out of circulation. If no new money is added, the money supply will decrease as a result; this shrinks the economy (mathematically it must absolutely shrink it in nominal terms; theoretically it could cause deflation and not reduce real output, but in practice real output always goes down because deflation causes its own set of problems). New money can be created by banks, but the mechanism of creation requires that people go further into debt. This is unstable, and eventually people can’t borrow anymore and the whole financial system comes crashing down. The better way, then, is for the government to create new money. Yes, as we currently do things, this means the government will go further into debt; but that’s all right, because the government can continue to increase its debt indefinitely without having to worry about hitting a ceiling and making everything fall apart. We could also just print money instead, and in fact I think in many cases this is what we should do—but for whatever reason people always freak out when you suggest such a thing, invariably mentioning Zimbabwe. (And yes, Zimbabwe is in awful shape; but they didn’t just print money to cover a reasonable amount of deficit spending. They printed money to line their own pockets, and it was thousands of times more than what I’m suggesting. Also Zimbabwe has a much smaller economy; $1 trillion is 5% of US GDP, but it’s 8,000% of Zimbabwe’s. I’m suggesting we print maybe 4% of GDP; at the peak of the hyperinflation they printed something more like 100,000%.)

One last thing before I go. If investment suddenly drops, net saving will go up. If the government deficit and trade deficit remain constant, profits must go down. This drives firms into bankruptcy, driving wages down as well. This makes GDP fall—and you get a recession. A similar effect would occur if consumption suddenly drops. In both cases people will be trying to increase their net wealth, but in fact they won’t be able to—this is what’s called the paradox of thrift. You actually want to increase the government deficit under these circumstances, because then you will both add to GDP directly and allow profits and wages to go back up and raise GDP even further. Because GDP has gone down, tax income will go down, so if you insist on balancing the budget, you’ll cut spending and only make things worse.

Raising the government deficit generally increases economic growth. From these simple equations it looks like you could raise GDP indefinitely, but these are nominal figures—actual dollar amounts—so after a certain point all you’d be doing is creating inflation. Where exactly that point is depends on how your economy is performing relative to its potential capacity. In a recession you are far below capacity, so that’s just the time to spend. You’d only want a budget surplus if you actually thought you were above long-run capacity, because you’re depleting natural resources or causing too much inflation or something like that. And indeed, we hardly ever see budget surpluses.

So that, my dear reader, is why we don’t need to fear the deficit. Government debt is nothing like other forms of debt; profits and savings depend upon the government spending more than it takes in; deficits are highly beneficial during recessions; and the US government is actually in a unique position to never worry about defaulting on its debt.