Apr 14 JDN 2460416

We are living in a very weird time, economically. The COVID pandemic created huge disruptions throughout our economy, from retail shops closing to shortages in shipping containers. The result was a severe recession with the worst unemployment since the Great Depression.

Now, a few years later, we have fully recovered.

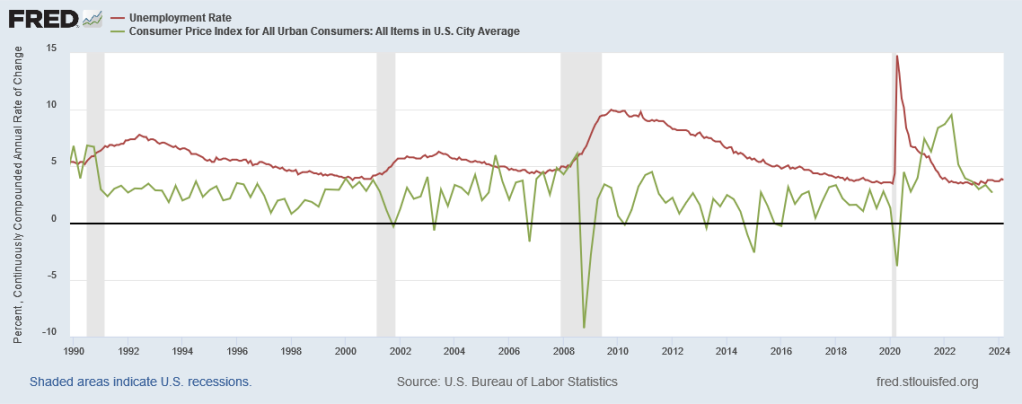

Here’s a graph from FRED showing our unemployment and inflation rates since 1990 [technical note: I’m using the urban CPI; there are a few other inflation measures you could use instead, but they look much the same]:

Inflation fluctuates pretty quickly, while unemployment moves much slower.

There are a lot of things we can learn from this graph:

- Before COVID, we had pretty low inflation; from 1990 to 2019, inflation averaged about 2.4%, just over the Fed’s 2% target.

- Before COVID, we had moderate to high unemployment; it rarely went below 5% and and for several years after the 2008 crash it was over 7%—which is why we called it the Great Recession.

- The only times we actually had negative inflation—deflation—were during recessions, and coincided with high unemployment; so, no, we really don’t want prices to come down.

- During COVID, we had a massive spike in unemployment up to almost 15%, but then it came back down much more rapidly than it had in the Great Recession.

- After COVID, there was a surge in inflation, peaking at almost 10%.

- That inflation surge was short-lived; by the end of 2022 inflation was back down to 4%.

- Unemployment now stands at 3.8% while inflation is at 2.7%.

What I really want to emphasize right now is point 7, so let me repeat it:

Unemployment now stands at 3.8% while inflation is at 2.7%.

Yes, technically, 2.7% is above our inflation target. But honestly, I’m not sure it should be. I don’t see any particular reason to think that 2% is optimal, and based on what we’ve learned from the Great Recession, I actually think 3% or even 4% would be perfectly reasonable inflation targets. No, we don’t want to be going into double-digits (and we certainly don’t want true hyperinflation); but 4% inflation really isn’t a disaster, and we should stop treating it like it is.

2.7% inflation is actually pretty close to the 2.4% inflation we’d been averaging from 1990 to 2019. So I think it’s fair to say that inflation is back to normal.

But the really wild thing is that unemployment isn’t back to normal: It’s much better than that.

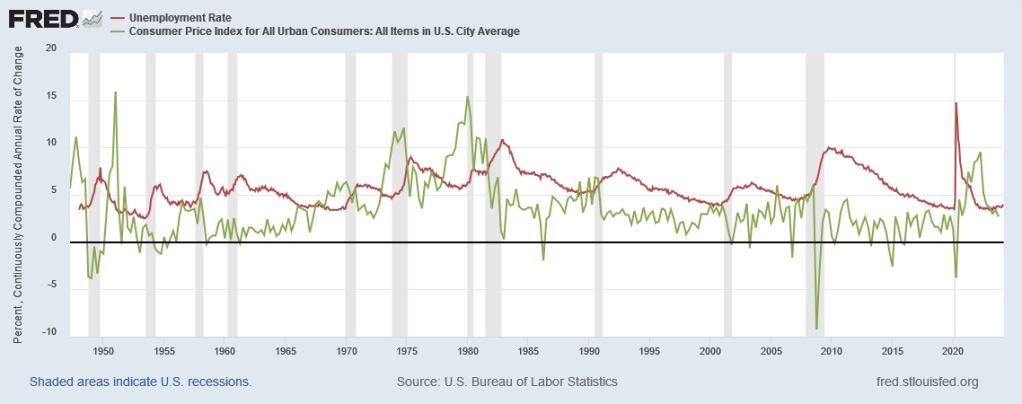

To get some more perspective on this, let’s extend our graph backward all the way to 1950:

Inflation has been much higher than it is now. In the late 1970s, it was consistently as high as it got during the post-COVID surge. But it has never been substantially lower than it is now; a little above the 2% target really seems to be what stable, normal inflation looks like in the United States.

On the other hand, unemployment is almost never this low. It was for a few years in the early 1950s and the late 1960s; but otherwise, it has always been higher—and sometimes much higher. It did not dip below 5% for the entire period from 1971 to 1994.

They hammer into us in our intro macroeconomics courses the Phillips Curve, which supposedly says that unemployment is inversely related to inflation, so that it’s impossible to have both low inflation and low unemployment.

But we’re looking at it, right now. It’s here, right in front of us. What wasn’t supposed to be possible has now been achieved. E pur si muove.

There was supposed to be this terrible trade-off between inflation and unemployment, leaving our government with the stark dilemma of either letting prices surge or letting millions remain out of work. I had always been on the “inflation” side: I thought that rising prices were far less of a problem than poeple out of work.

But we just learned that the entire premise was wrong.

You can have both. You don’t have to choose.

Right here, right now, we have both. All we need to do is keep doing whatever we’re doing.

One response might be: what if we can’t? What if this is unsustainable? (Then again, conservatives never seemed terribly concerned about sustainability before….)

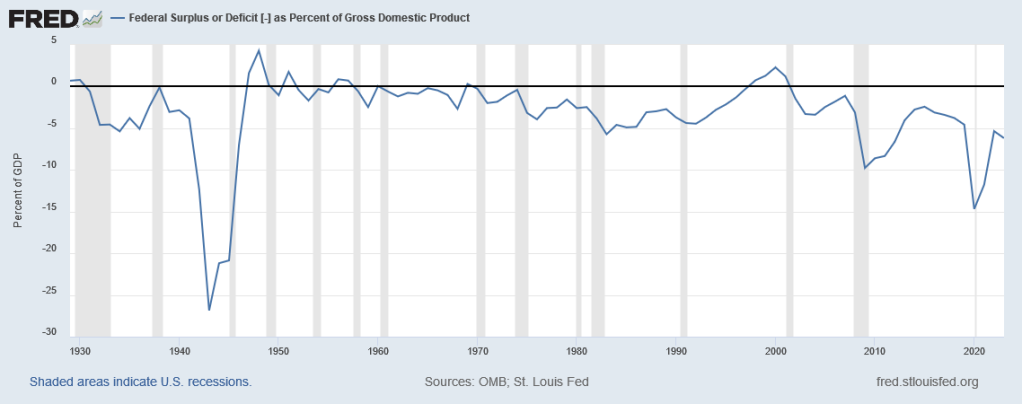

It’s worth considering. One thing that doesn’t look so great now is the federal deficit. It got extremely high during COVID, and it’s still pretty high now. But as a proportion of GDP, it isn’t anywhere near as high as it was during WW2, and we certainly made it through that all right:

So, yeah, we should probably see if we can bring the budget back to balanced—probably by raising taxes. But this isn’t an urgent problem. We have time to sort it out. 15% unemployment was an urgent problem—and we fixed it.

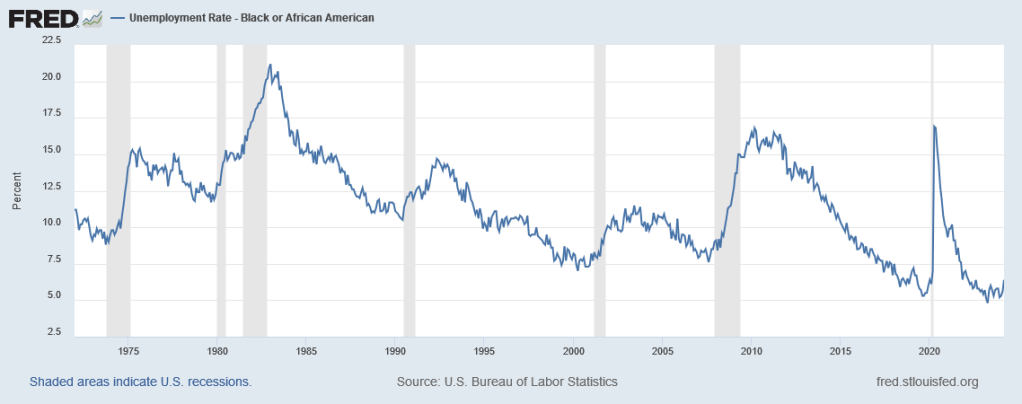

In fact in some ways the economy is even doing better now than it looks. Unemployment for Black people has never been this low, since we’ve been keeping track of it:

Black people had basically learned to live with 8% or 9% unemployment as if it were normal; but now, for the first time ever—ever—their unemployment rate is down to only 5%.

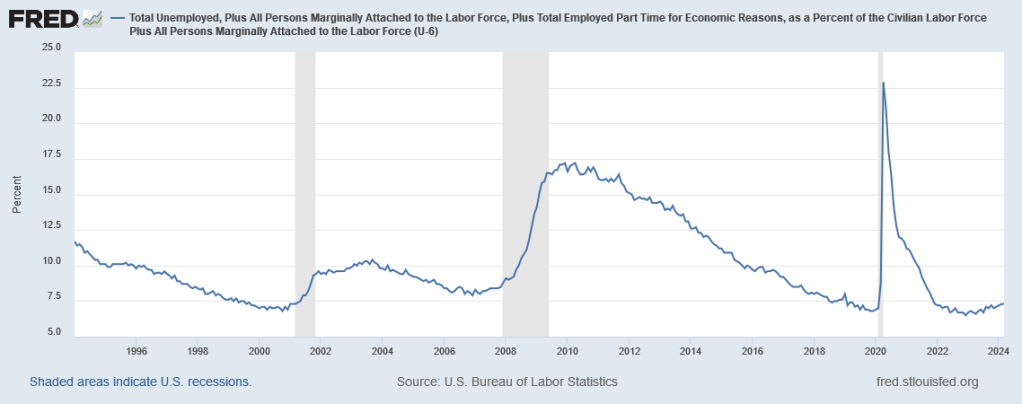

This isn’t because people are dropping out of the labor force. Broad unemployment, which includes people marginally attached to the labor force, people employed part-time not by choice, and people who gave up looking for work, is also at historic lows, despite surging to almost 23% during COVID:

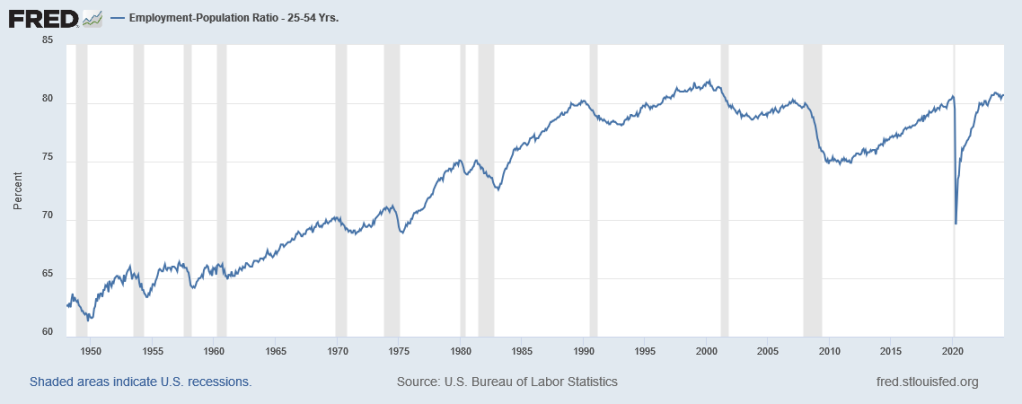

In fact, overall employment among people 25-54 years old (considered “prime age”—old enough to not be students, young enough to not be retired) is nearly the highest it has ever been, and radically higher than it was before the 1980s (because women entered the workforce):

So this is not an illusion: More Americans really are working now. And employment has become more inclusive of women and minorities.

I really don’t understand why President Biden isn’t more popular. Biden inherited the worst unemployment since the Great Depression, and turned it around into an economic situation so good that most economists thought it was impossible. A 39% approval rating does not seem consistent with that kind of staggering economic improvement.

And yes, there are a lot of other factors involved aside from the President; but for once I think he really does deserve a lot of the credit here. Programs he enacted to respond to COVID brought us back to work quicker than many thought possible. Then, the Inflation Reduction Act made historic progress at fighting climate change—and also, lo and behold, reduced inflation.

He’s not a particularly charismatic figure. He is getting pretty old for this job (or any job, really). But Biden’s economic policy has been amazing, and deserves more credit for that.