Aug 3 JDN 2460891

Today I finally got around to reading Expert Political Judgment by Philip E. Tetlock, more or less in a single sitting because I’ve been sick the last week with some pretty tight limits on what activities I can do. (It’s mostly been reading, watching TV, or playing video games that don’t require intense focus.)

It’s really an excellent book, and I now both understand why it came so highly recommended to me, and now pass on that recommendation to you: Read it.

The central thesis of the book really boils down to three propositions:

- Human beings, even experts, are very bad at predicting political outcomes.

- Some people, who use an open-minded strategy (called “foxes”), perform substantially better than other people, who use a more dogmatic strategy (called “hedgehogs”).

- When rewarding predictors with money, power, fame, prestige, and status, human beings systematically favor (over)confident “hedgehogs” over (correctly) humble “foxes”.

I decided I didn’t want to make this post about current events, but I think you’ll probably agree with me when I say:

That explains a lot.

How did Tetlock determine this?

Well, he studies the issue several different ways, but the core experiment that drives his account is actually a rather simple one:

- He gathered a large group of subject-matter experts: Economists, political scientists, historians, and area-studies professors.

- He came up with a large set of questions about politics, economics, and similar topics, which could all be formulated as a set of probabilities: “How likely is this to get better/get worse/stay the same?” (For example, this was in the 1980s, so he asked about the fate of the Soviet Union: “By 1990, will they become democratic, remain as they are, or collapse and fragment?”)

- Each respondent answered a subset of the questions, some about their own particular field, some about another, more distant field; they assigned probabilities on an 11-point scale, from 0% to 100% in increments of 10%.

- A few years later, he compared the predictions to the actual results, scoring them using a Brier score, which penalizes you for assigning high probability to things that didn’t happen or low probability to things that did happen.

- He compared the resulting scores between people with different backgrounds, on different topics, with different thinking styles, and a variety of other variables. He also benchmarked them using some automated algorithms like “always say 33%” and “always give ‘stay the same’ 100%”.

I’ll show you the key results of that analysis momentarily, but to help it make more sense to you, let me elaborate a bit more on the “foxes” and “hedgehogs”. The notion is was first popularized by Isaiah Berlin in an essay called, simply, The Hedgehog and the Fox.

“The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one very big thing.”

That is, someone who reasons as a “fox” combines ideas from many different sources and perspective, and tries to weigh them all together into some sort of synthesis that then yields a final answer. This process is messy and complicated, and rarely yields high confidence about anything.

Whereas, someone who reasons as a “hedgehog” has a comprehensive theory of the world, an ideology, that provides clear answers to almost any possible question, with the surely minor, insubstantial flaw that those answers are not particularly likely to be correct.

He also considered “hedge-foxes” (people who are mostly fox but also a little bit hedgehog) and “fox-hogs” (people who are mostly hedgehog but also a little bit fox).

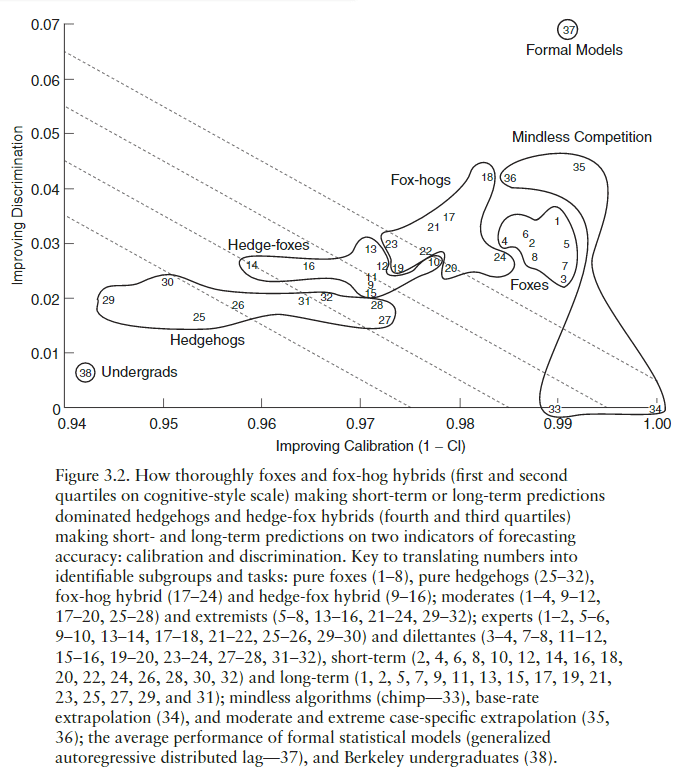

Tetlock has decomposed the scores into two components: calibration and discrimination. (Both very overloaded words, but they are standard in the literature.)

Calibration is how well your stated probabilities matched up with the actual probabilities; that is, if you predicted 10% probability on 20 different events, you have very good calibration if precisely 2 of those events occurred, and very poor calibration if 18 of those events occurred.

Discrimination more or less describes how useful your predictions are, what information they contain above and beyond the simple base rate. If you just assign equal probability to all events, you probably will have reasonably good calibration, but you’ll have zero discrimination; whereas if you somehow managed to assign 100% to everything that happened and 0% to everything that didn’t, your discrimination would be perfect (and we would have to find out how you cheated, or else declare you clairvoyant).

For both measures, higher is better. The ideal for each is 100%, but it’s virtually impossible to get 100% discrimination and actually not that hard to get 100% calibration if you just use the base rates for everything.

There is a bit of a tradeoff between these two: It’s not too hard to get reasonably good calibration if you just never go out on a limb, but then your predictions aren’t as useful; we could have mostly just guessed them from the base rates.

On the graph, you’ll see downward-sloping lines that are meant to represent this tradeoff: Two prediction methods that would yield the same overall score but different levels of calibration and discrimination will be on the same line. In a sense, two points on the same line are equally good methods that prioritize usefulness over accuracy differently.

All right, let’s see the graph at last:

The pattern is quite clear: The more foxy you are, the better you do, and the more hedgehoggy you are, the worse you do.

I’d also like to point out the other two regions here: “Mindless competition” and “Formal models”.

The former includes really simple algorithms like “always return 33%” or “always give ‘stay the same’ 100%”. These perform shockingly well. The most sophisticated of these, “case-specific extrapolation” (35 and 36 on the graph, which basically assumes that each country will continue doing what it’s been doing) actually performs as well if not better than even the foxes.

And what’s that at the upper-right corner, absolutely dominating the graph? That’s “Formal models”. This describes basically taking all the variables you can find and shoving them into a gigantic logit model, and then outputting the result. It’s computationally intensive and requires a lot of data (hence why he didn’t feel like it deserved to be called “mindless”), but it’s really not very complicated, and it’s the best prediction method, in every way, by far.

This has made me feel quite vindicated about a weird nerd thing I do: When I have a big decision to make (especially a financial decision), I create a spreadsheet and assemble a linear utility model to determine which choice will maximize my utility, under different parameterizations based on my past experiences. Whichever result seems to win the most robustly, I choose. This is fundamentally similar to the “formal models” prediction method, where the thing I’m trying to predict is my own happiness. (It’s a bit less formal, actually, since I don’t have detailed happiness data to feed into the regression.) And it has worked for me, astonishingly well. It definitely beats going by my own gut. I highly recommend it.

What does this mean?

Well first of all, it means humans suck at predicting things. At least for this data set, even our experts don’t perform substantially better than mindless models like “always assume the base rate”.

Nor do experts perform much better in their own fields than in other fields; they do all perform better than undergrads or random people (who somehow perform worse than the “mindless” models)

But Tetlock also investigates further, trying to better understand this “fox/hedgehog” distinction and why it yields different performance. He really bends over backwards to try to redeem the hedgehogs, in the following ways:

- He allows them to make post-hoc corrections to their scores, based on “value adjustments” (assigning higher probability to events that would be really important) and “difficulty adjustments” (assigning higher scores to questions where the three outcomes were close to equally probable) and “fuzzy sets” (giving some leeway on things that almost happened or things that might still happen later).

- He demonstrates a different, related experiment, in which certain manipulations can cause foxes to perform a lot worse than they normally would, and even yield really crazy results like probabilities that add up to 200%.

- He has a whole chapter that is a Socratic dialogue (seriously!) between four voices: A “hardline neopositivist”, a “moderate neopositivist”, a “reasonable relativist”, and an “unrelenting relativist”; and all but the “hardline neopositivist” agree that there is some legitimate place for the sort of post hoc corrections that the hedgehogs make to keep themselves from looking so bad.

This post is already getting a bit long, so that will conclude part I. Stay tuned for part II, next week!