Aug 3 JDN 2460891

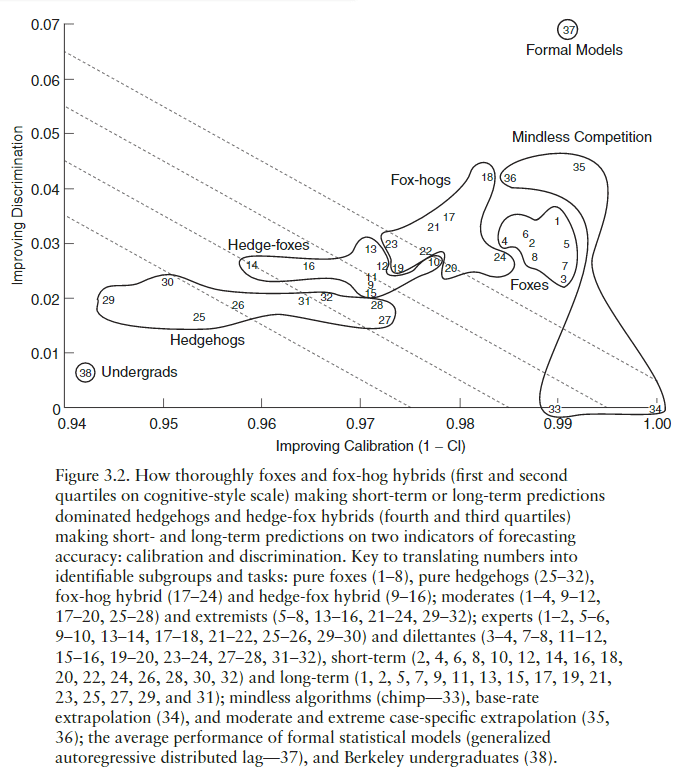

In last week’s post I described Philip E. Tetlock’s experiment showing that “foxes” (people who are open-minded and willing to consider alternative views) make more accurate predictions than “hedgehogs” (people who are dogmatic and conform strictly to a single ideology).

As I explained at the end of the post, he, uh, hedges on this point quite a bit, coming up with various ways that the hedgehogs might be able to redeem themselves, but still concluding that in most circumstances, the foxes seem to be more accurate.

Here are my thoughts on this:

I think he went too easy on the hedgehogs.

I consider myself very much a fox, and I honestly would never assign a probability of 0% or 100% to any physically possible event. Honestly I consider it a flaw in Tetlock’s design that he included those as options but didn’t include probabilities I would assign, like 1%, 0.1%, or 0.01%.

He only let people assign probabilities in 10% increments. So I guess if you thought something was 3% likely, you’re supposed to round to 0%? That still feels terrible. I’d probably still write 10%. There weren’t any questions like “Aliens from the Andromeda Galaxy arrive to conquer our planet, thus rendering all previous political conflicts moot”, but man, had there been, I’d still be tempted to not put 0%. I guess I would put 0% for that though? Because in 99.999999% of cases, I’d get it right—it wouldn’t happen—and I’d get more points. But man, even single-digit percentages? I’d mash the 10% button. I am pretty much allergic to overconfidence.

In fact, I think in my mind I basically try to use a logarithmic score, which unlike a Brier score, severely (technically, infinitely) punishes you for saying that something impossible happened or something inevitable didn’t. Like, really, if you’re doing it right, that should never, ever happen to you. If you assert that something has 0% probability and it happens, you have just conclusively disproven your worldview. (Admittedly it’s possible you could fix it with small changes—but a full discussion of that would get us philosophically too far afield. “outside the scope of this paper”.)

So honestly I think he was too lenient on overconfidence by using a Brier score, which does penalize this kind of catastrophic overconfidence, but only by a moderate amount. If you say that something has a 0% chance and then it happens, you get a Brier score of -1. But if you say that something has a 50% chance and then it happens (which it would, you know, 50% of the time), you’d get a Brier score of -0.25. So even absurd overconfidence isn’t really penalized that badly.

Compare this to a logarithmic rule: Say 0% and it happens, and you get negative infinity. You lose. You fail. Go home. Your worldview is bad and you should feel bad. This should never happen to you if you have a coherent worldview (modulo the fact that he didn’t let you say 0.01%).

So if I had designed this experiment, I would have given finer-grained options at the extremes, and then brought the hammer down on anybody who actually asserted a 0% chance of an event that actually occurred. (There’s no need for the finer-grained options elsewhere; over millennia of history, the difference between 0% and 0.1% is whether it won’t happen or it will—quite relevant for, say, full-scale nuclear war—while the difference between 40% and 42.1% is whether it’ll happen every 2 to 3 years or… every 2 to 3 years.)

But okay, let’s say we stick with the Brier score, because infinity is scary.

- About the adjustments:

- The “value adjustments” are just absolute nonsense. Those would be reasons to adjust your policy response, via your utility function—they are not a reason to adjust your probability. Yes, a nuclear terrorist attack would be a really big deal if it happened and we should definitely be taking steps to prevent that; but that doesn’t change the fact that the probability of one happening is something like 0.1% per year and none have ever happened. Predicting things that don’t happen is bad forecasting, even if the things you are predicting would be very important if they happened.

- The “difficulty adjustments” are sort of like applying a different scoring rule, so that I’m more okay with; but that wasn’t enough to make the hedgehogs look better than the foxes.

- The “fuzzy set” adjustments could be legitimate, but only under particular circumstances. Being “almost right” is only valid if you clearly showed that the result was anomalous because of some other unlikely event, and—because the timeframe was clearly specified in the questions—“might still happen” should still get fewer points than accurately predicting that it hasn’t happened yet. Moreover, it was very clear that people only ever applied these sort of changes when they got things wrong; they rarely if ever said things like “Oh, wow, I said that would happen and it did, but for completely different reasons that I didn’t expect—I was almost wrong there.” (Crazy example, but if the Soviet Union had been taken over by aliens, “the Soviet Union will fall” would be correct—but I don’t think you could really attribute that to good political prediction.)

- The second exercise shows that even the foxes are not great Bayesians, and that some manipulations can make people even more inaccurate than before; but the hedgehogs also perform worse and also make some of the same crazy mistakes and still perform worse overall than the foxes, even in that experiment.

- I guess he’d call me a “hardline neopositivist”? Because I think that your experiment asking people to predict things should require people to, um, actually predict things? The task was not to get the predictions wrong but be able to come up with clever excuses for why they were wrong that don’t challenge their worldview. The task was to not get the predictions wrong. Apparently this very basic level of scientific objectivity is now considered “hardline neopositivism”.

I guess we can reasonably acknowledge that making policy is about more than just prediction, and indeed maybe being consistent and decisive is advantageous in a game-theoretic sense (in much the same way that the way to win a game of Chicken is to very visibly throw away your steering wheel). So you could still make a case for why hedgehogs are good decision-makers or good leaders.

But I really don’t see how you weasel out of the fact that hedgehogs are really bad predictors. If I were running a corporation, or a government department, or an intelligence agency, I would want accurate predictions. I would not be interested in clever excuses or rich narratives. Maybe as leaders one must assemble such narratives in order to motivate people; so be it, there’s a division of labor there. Maybe I’d have a separate team of narrative-constructing hedgehogs to help me with PR or something. But the people who are actually analyzing the data should be people who are good at making accurate predictions, full stop.

And in fact, I don’t think hedgehogs are good decision-makers or good leaders. I think they are good politicians. I think they are good at getting people to follow them and believe what they say. But I do not think they are actually good at making the decisions that would be the best for society.

Indeed, I think this is a very serious problem.

I think we systematically elect people to higher office—and hire them for jobs, and approve them for tenure, and so on—because they express confidence rather than competence. We pick the people who believe in themselves the most, who (by regression to the mean if nothing else) are almost certainly the people who are most over-confident in themselves.

Given that confidence is easier to measure than competence in most areas, it might still make sense to choose confident people if confidence were really positively correlated with competence, but I’m not convinced that it is. I think part of what Tetlock is showing us is that the kind of cognitive style that yields high confidence—a hedgehog—simply is not the kind of cognitive style that yields accurate beliefs—a fox. People who are really good at their jobs are constantly questioning themselves, always open to new ideas and new evidence; but that also means that they hedge their bets, say “on the other hand” a lot, and often suffer from Impostor Syndrome. (Honestly, testing someone for Impostor Syndrome might be a better measure of competence than a traditional job interview! Then again, Goodhart’s Law.)

Indeed, I even see this effect within academic science; the best scientists I know are foxes through and through, but they’re never the ones getting published in top journals and invited to give keynote speeches at conferences. The “big names” are always hedgehog blowhards with some pet theory they developed in the 1980s that has failed to replicate but somehow still won’t die.

Moreover, I would guess that trustworthiness is actually pretty strongly inversely correlated to confidence—“con artist” is short for “confidence artist”, after all.

Then again, I tried to find rigorous research comparing openness (roughly speaking “fox-ness”) or humility to honesty, and it was surprisingly hard to find. Actually maybe the latter is just considered an obvious consensus in the literature, because there is a widely-used construct called honesty-humility. (In which case, yeah, my thinking on trustworthiness and confidence is an accepted fact among professional psychologists—but then, why don’t more people know that?)

But that still doesn’t tell me if there is any correlation between honesty-humility and openness.

I did find these studies showing that both honesty-humility and openness are both positively correlated with well-being, both positively correlated with cooperation in experimental games, and both positively correlated with being left-wing; but that doesn’t actually prove they are positively correlated with each other. I guess it provides weak evidence in that direction, but only weak evidence. It’s entirely possible for A to be positively correlated with both B and C but B and C are uncorrelated or negatively correlated. (Living in Chicago is positively correlated with being a White Sox fan and positively correlated with being a Cubs fan, but being a White Sox fan is not positively correlated with being a Cubs fan!)

I also found studies showing that higher openness predicts less right-wing authoritarianism and higher honesty predicts less social conformity; but that wasn’t the question either.

Here’s a factor analysis specifically arguing for designing measures of honesty-humility so that they don’t correlate with other personality traits, so it can be seen as its own independent personality trait. There are some uncomfortable degrees of freedom in designing new personality metrics, which may make this sort of thing possible; and then by construction honesty-humility and openness would be uncorrelated, because any shared components were parceled out to one trait or the other.

So, I guess I can’t really confirm my suspicion here; maybe people who think like hedgehogs aren’t any less honest, or are even more honest, than people who think like foxes. But I’d still bet otherwise. My own life experience has been that foxes are honest and humble while hedgehogs are deceitful and arrogant.

Indeed, I believe that in systematically choosing confident hedgehogs as leaders, the world economy loses tens of trillions of dollars a year in inefficiencies. In fact, I think that we could probably end world hunger if we only ever put leaders in charge who were both competent and trustworthy.

Of course, in some sense that’s a pipe dream; we’re never going to get all good leaders, just as we’ll never get zero death or zero crime.

But based on how otherwise-similar countries have taken wildly different trajectories based on differences in leadership, I suspect that even relatively small changes in that direction could have quite large impacts on a society’s outcomes: South Korea isn’t perfect at picking its leaders; but surely it’s better than North Korea, and indeed that seems like one of the primary things that differentiates the two countries. Botswana is not a utopian paradise, but it’s a much nicer place to live than Nigeria, and a lot of the difference seems to come down to who is in charge, or who has been in charge for the last few decades.

And I could put in a jab here about the current state of the United States, but I’ll resist. If you read my blog, you already know my opinions on this matter.