Dec 10 JDN 2460290

I don’t think most Americans realize just how much more the US spends on healthcare than other countries. This is true not simply in absolute terms—of course it is, the US is rich and huge—but in relative terms: As a portion of GDP, our healthcare spending is a major outlier.

Here’s a really nice graph from Healthsystemtracker.org that illustrates it quite nicely: Almost all other First World countries share a simple linear relationship between their per-capita GDP and their per-capita healthcare spending. But one of these things is not like the other ones….

The outlier in the other direction is Ireland, but that’s because their GDP is wildly inflated by Leprechaun Economics. (Notice that it looks like Ireland is by far the richest country in the sample! This is clearly not the case in reality.) With a corrected estimate of their true economic output, they are also quite close to the line.

Since US GDP per capita ($70,181) is in between that of Denmark ($64,898) and Norway ($80,496) both of which have very good healthcare systems (#ScandinaviaIsBetter), we would expect that US spending on healthcare would similarly be in between. But while Denmark spends $6,384 per person per year on healthcare and Norway spends $7,065 per person per year, the US spends $12,914.

That is, the US spends nearly twice as much as it should on healthcare.

The absolute difference between what we should spend and what we actually spend is nearly $6,000 per person per year. Multiply that out by the 330 million people in the US, and…

The US overspends on healthcare by nearly $2 trillion per year.

This might be worth it, if health in the US were dramatically better than health in other countries. (In that case I’d be saying that other countries spend too little.) But plainly it is not.

Probably the simplest and most comparable measure of health across countries is life expectancy. US life expectancy is 76 years, and has increased over time. But if you look at the list of countries by life expectancy, the US is not even in the top 50. Our life expectancy looks more like middle-income countries such as Algeria, Brazil, and China than it does like Norway or Sweden, who should be our economic peers.

There are of course many things that factor into life expectancy aside from healthcare: poverty and homicide are both much worse in the US than in Scandinavia. But then again, poverty is much worse in Algeria, and homicide is much worse in Brazil, and yet they somehow manage to nearly match the US in life expectancy (actually exceeding it in some recent years).

The US somehow manages to spend more on healthcare than everyone else, while getting outcomes that are worse than any country of comparable wealth—and even some that are far poorer.

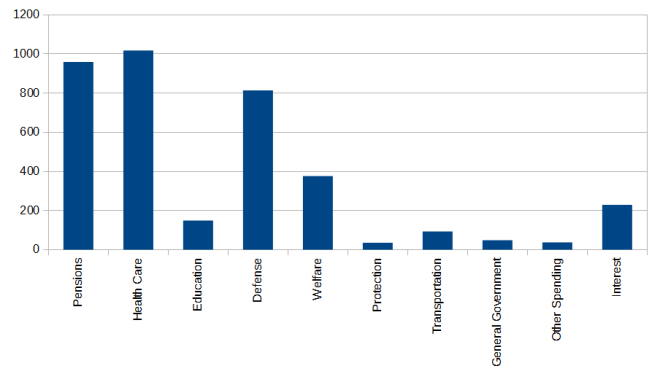

This is largely why there is a so-called “entitlements crisis” (as many a libertarian think tank is fond of calling it). Since libertarians want to cut Social Security most of all, they like to lump it in with Medicare and Medicaid as an “entitlement” in “crisis”; but in fact we only need a few minor adjustments to the tax code to make sure that Social Security remains solvent for decades to come. It’s healthcare spending that’s out of control.

Here, take a look.

This is the ratio of Social Security spending to GDP from 1966 to the present. Notice how it has been mostly flat since the 1980s, other than a slight increase in the Great Recession.

This is the ratio of Medicare spending to GDP over the same period. Even ignoring the first few years while it was ramping up, it rose from about 0.6% in the 1970s to almost 4% in 2020, and only started to decline in the last few years (and it’s probably too early to say whether that will continue).

Medicaid has a similar pattern: It rose steadily from 0.2% in 1966 to over 3% today—and actually doesn’t even show any signs of leveling off.

If you look at Medicare and Medicaid together, they surged from just over 1% of GDP in 1970 to nearly 7% today:

Put another way: in 1982, Social Security was 4.8% of GDP while Medicare and Medicaid combined were 2.4% of GDP. Today, Social Security is 4.9% of GDP while Medicare and Medicaid are 6.8% of GDP.

Social Security spending barely changed at all; healthcare spending more than doubled. If we reduced our Medicare and Medicaid spending as a portion of GDP back to what it was in 1982, we would save 4.4% of GDP—that is, 4.4% of over $25 trillion per year, so $1.1 trillion per year.

Of course, we can’t simply do that; if we cut benefits that much, millions of people would suddenly lose access to healthcare they need.

The problem is not that we are spending frivolously, wasting the money on treatments no one needs. On the contrary, both Medicare and Medicaid carefully vet what medical services they are willing to cover, and if anything probably deny services more often than they should.

No, the problem runs deeper than this.

Healthcare is too expensive in the United States.

We simply pay more for just about everything, and especially for specialist doctors and hospitals.

In most other countries, doctors are paid like any other white-collar profession. They are well off, comfortable, certainly, but few of them are truly rich. But in the US, we think of doctors as an upper-class profession, and expect them to be rich.

Median doctor salaries are $98,000 in France and $138,000 in the UK—but a whopping $316,000 in the US. Germany and Canada are somewhere in between, at $183,000 and $195,000 respectively.

Nurses, on the other hand, are paid only a little more in the US than in Western Europe. This means that the pay difference between doctors and nurses is much higher in the US than most other countries.

US prices on brand-name medication are frankly absurd. Our generic medications are typically cheaper than other countries, but our brand name pills often cost twice as much. I noticed this immediately on moving to the UK: I had always been getting generics before, because the brand name pills cost ten times as much, but when I moved here, suddenly I started getting all brand-name medications (at no cost to me), because the NHS was willing to buy the actual brand name products, and didn’t have to pay through the nose to do so.

But the really staggering differences are in hospitals.

Let’s compare the prices of a few inpatient procedures between the US and Switzerland. Switzerland, you should note, is a very rich country that spends a lot on healthcare and has nearly the world’s highest life expectancy. So it’s not like they are skimping on care. (Nor is it that prices in general are lower in Switzerland; on the contrary, they are generally higher.)

A coronary bypass in Switzerland costs about $33,000. In the US, it costs $76,000.

A spinal fusion in Switzerland costs about $21,000. In the US? $52,000.

Angioplasty in Switzerland: $9.000. In the US? $32,000.

Hip replacement: Switzerland? $16,000. The US? $28,000.

Knee replacement: Switzerland? $19,000. The US? $27,000.

Cholecystectomy: Switzerland? $8,000. The US? $16,000.

Appendectomy: Switzerland? $7,000. The US? $13,000.

Caesarian section: Switzerland? $8,000. The US? $11,000.

Hospital prices are even lower in Germany and Spain, whose life expectancies are not as high as Switzerland—but still higher than the US.

These prices are so much lower that in fact if you were considering getting surgery for a chronic condition in the US, don’t. Buy plane tickets to Europe and get the procedure done there. Spend an extra few thousand dollars on a nice European vacation and you’d still end up saving money. (Obviously if you need it urgently you have no choice but to use your nearest hospital.) I know that if I ever need a knee replacement (which, frankly, is likely, given my height), I’m gonna go to Spain and thereby save $22,000 relative to what it would cost in the US. That’s a difference of a car.

Combine this with the fact that the US is the only First World country without universal healthcare, and maybe you can see why we’re also the only country in the world where people are afraid to call an ambulance because they don’t think they can afford it. We are also the only country in the world with a medical debt crisis.

Where is all this extra money going?

Well, a lot of it goes to those doctors who are paid three times as much as in France. That, at least, seems defensible: If we want the best doctors in the world maybe we need to pay for them. (Then again, do we have the best doctors in the world? If so, why is our life expectancy so mediocre?)

But a significant portion is going to shareholders.

You probably already knew that there are pharmaceutical companies that rake in huge profits on those overpriced brand-name medications. The top five US pharma companies took in net earnings of nearly $82 billion last year. Pharmaceutical companies typically take in much higher profit margins than other companies: a typical corporation makes about 8% of its revenue in profit, while pharmaceutical companies average nearly 14%.

But you may not have realized that a surprisingly large proportion of hospitals are for-profit businesses—even though they make most of their revenue from Medicare and Medicaid.

I was surprised to find that the US is not unusual in that; in fact, for-profit hospitals exist in dozens of countries, and the fraction of US hospital capacity that is for-profit isn’t even particularly high by world standards.

What is especially large is the profits of US hospitals. 7 healthcare corporations in the US all posted net incomes over $1 billion in 2021.

Even nonprofit US hospitals are tremendously profitable—as oxymoronic as that may sound. In fact, mean operating profit is higher among nonprofit hospitals in the US than for-profit hospitals. So even the hospitals that aren’t supposed to be run for profit… pretty much still are. They get tax deductions as if they were charities—but they really don’t act like charities.

They are basically nonprofit in name only.

So fixing this will not be as simple as making all hospitals nonprofit. We must also restructure the institutions so that nonprofit hospitals are genuinely nonprofit, and no longer nonprofit in name only. It’s normal for a nonprofit to have a little bit of profit or loss—nobody can make everything always balance perfectly—but these hospitals have been raking in huge profits and keeping it all in cash instead of using it to reduce prices or improve services. In the study I linked above, those 2,219 “nonprofit” hospitals took in operating profits averaging $43 million each—for a total of $95 billion.

Between pharmaceutical companies and hospitals, that’s a total of over $170 billion per year just in profit. (That’s more than we spend on food stamps, even after surge due to COVID.) This is pure grift. It must be stopped.

But that still doesn’t explain why we’re spending $2 trillion more than we should! So after all, I must leave you with a question:

What is America doing wrong? Why is our healthcare so expensive?