Apr 13 JDN 2460779

On the one hand, I’m sure every economics blog on the Internet is already talking about this, including Paul Krugman who knows the subject way better than I ever will (and literally won a Nobel Prize for his work on it). And I have other things I’d rather be writing about, like the Index of Necessary Expenditure. But on the other hand, when something this big happens in economics, it just feels like there’s really no alternative: I have to talk about tariffs right now.

What is a tariff, anyway?

This feels like a really basic question, but it also seems like a lot of people don’t really understand tariffs, or didn’t when they voted for Trump.

A tariff, quite simply, is an import tax. It’s a tax that you impose on imported goods (either a particular kind, or from a particular country, or just across the board). On paper, it is generally paid by the company importing the goods, but as I wrote about in my sequence on tax incidence, that doesn’t matter. What matters is how prices change in response to the tax, and this means that in real terms, prices will go up.

In fact, in some sense that’s the goal of a protectionist tariff, because you’re trying to fix the fact that local producers can’t compete on the global market. So you compensate by making international firms pay higher taxes, so that the local producers can charge higher prices and still compete. So anyone who is saying that tariffs won’t raise prices is either ignorant or lying: Raising prices is what tariffs do.

Why are people so surprised?

The thing that surprises me about all this, (a bit ironically) is how surprised people seem to be. Trump ran his whole campaign promising two things: Deport all the immigrants, and massive tariffs on all trade. Most of his messaging was bizarre and incoherent, but on those two topics he was very consistent. So why in the world are people—including stock traders, who are supposedly savvy on these things—so utterly shocked that he has actually done precisely what he promised he would do?

What did people think Trump meant when he said these things? Did they assume he was bluffing? Did they think cooler heads in his administration would prevail (if so, whose?)?

But I will admit that even I am surprised at just how big the tariffs are. I knew they would be big, but I did not expect them to be this big.

How big?

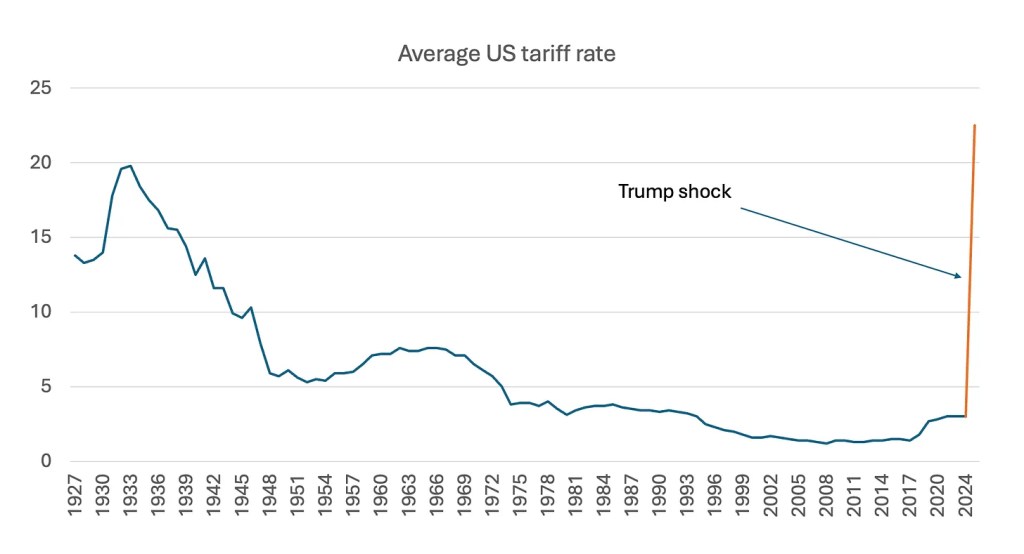

Well, take a look at this graph:

The average tariff rate on US imports will now be higher than it was at the peak in 1930 with the Smoot-Hawley Act. Moreover, Smoot-Hawley was passed during a time when protectionist tariffs were already in place, while Trump’s tariffs come at a time when tariffs had previously been near zero—so the change is dramatically more sudden.

This is worse than Smoot-Hawley.

For the uninitiated, Smoot-Hawley was a disaster. Several countries retaliated with their own tariffs, and the resulting trade war clearly exacerbated the Great Depression, not only in the US but around the world. World trade dropped by an astonishing 66% over the next few years. It’s still debated as to how much of the depression was caused by the tariffs; most economists believe that the gold standard was the bigger culprit. But it definitely made it worse.

Politically, the aftermath cost the Republicans (including Smoot and Hawley themselves) several seats in Congress. (I guess maybe the silver lining here is we can hope this will do the same?)

And I would now like to remind you that these tariffs are bigger than Smoot-Hawley’s and were implemented more suddenly.

Unlike in 1930, we are not currently in a depression—though nor is our economy as hunky-dory as a lot of pundits seem to think, once we consider things like the Index of Necessary Expenditure. But stock markets do seem to be crashing, and if trade drops as much as it did in the 1930s—and why wouldn’t it?—we may very well end up in another depression.

And it’s not as if we didn’t warn you all. Economists across the political spectrum have been speaking out against Trump’s tariffs from the beginning, and nobody listened to us.

So basically the mood of all economists right now is: