Mar 16 JDN 2460751

I’m still reeling from the fact that Donald Trump was re-elected President. He seemed obviously horrible at the time, and he still seems horrible now, for many of the same reasons as before (we all knew the tariffs were coming, and I think deep down we knew he would sell out Ukraine because he loves Putin), as well as some brand new ones (I did not predict DOGE would gain access to all the government payment systems, nor that Trump would want to start a “crypto fund”). Kamala Harris was not an ideal candidate, but she was a good candidate, and the comparison between the two could not have been starker.

Now that the dust has cleared and we have good data on voting patterns, I am now less convinced than I was that racism and sexism were decisive against Harris. I think they probably hurt her some, but given that she actually lost the most ground among men of color, racism seems like it really couldn’t have been a big factor. Sexism seems more likely to be a significant factor, but the fact that Harris greatly underperformed Hillary Clinton among Latina women at least complicates that view.

A lot of voters insisted that they voted on “inflation” or “the economy”. Setting aside for a moment how absurd it was—even at the time—to think that Trump (he of the tariffs and mass deportations!) was going to do anything beneficial for the economy, I would like to better understand how people could be so insistent that the economy was bad even though standard statistical measures said it was doing fine.

Krugman believes it was a “vibecession”, where people thought the economy was bad even though it wasn’t. I think there may be some truth to this.

But today I’d like to evaluate another possibility, that what people were really reacting against was not inflation per se but necessitization.

I first wrote about necessitization in 2020; as far as I know, the term is my own coinage. The basic notion is that while prices overall may not have risen all that much, prices of necessities have risen much faster, and the result is that people feel squeezed by the economy even as CPI growth remains low.

In this post I’d like to more directly evaluate that notion, by constructing an index of necessary expenditure (INE).

The core idea here is this:

What would you continue to buy, in roughly the same amounts, even if it doubled in price, because you simply can’t do without it?

For example, this is clearly true of housing: You can rent or you can own, but can’t not have a house. And nor are most families going to buy multiple houses—and they can’t buy partial houses.

It’s also true of healthcare: You need whatever healthcare you need. Yes, depending on your conditions, you maybe could go without, but not without suffering, potentially greatly. Nor are you going to go out and buy a bunch of extra healthcare just because it’s cheap. You need what you need.

I think it’s largely true of education as well: You want your kids to go to college. If college gets more expensive, you might—of necessity—send them to a worse school or not allow them to complete their degree, but this would feel like a great hardship for your family. And in today’s economy you can’t not send your kids to college.

But this is not true of technology: While there is a case to be made that in today’s society you need a laptop in the house, the fact is that people didn’t used to have those not that long ago, and if they suddenly got a lot cheaper you very well might buy another one.

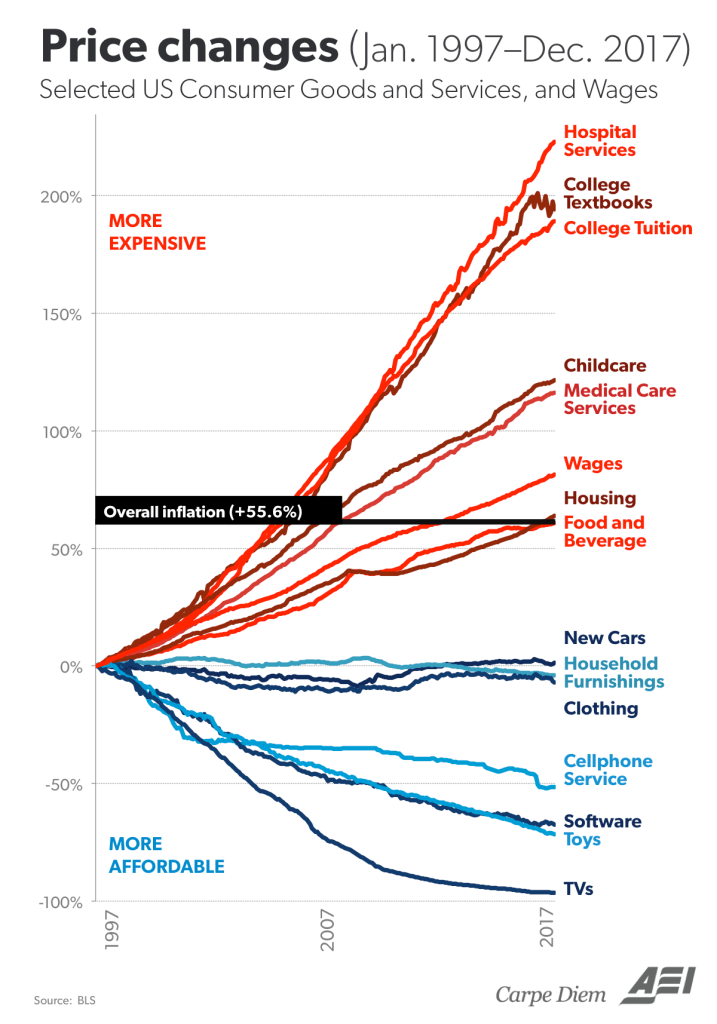

Well, it just so happens that housing, healthcare, and education have all gotten radically more expensive over time, while technology has gotten radically cheaper. So prima facie, this is looking pretty plausible.

But I wanted to get more precise about it. So here is the index I have constructed. I consider a family of four, two adults, two kids, making the median household income.

To get the median income, I’ll use this FRED series for median household income, then use this table of median federal tax burden to get an after-tax wage. (State taxes vary too much for me to usefully include them.) Since the tax table ends in 2020 which was anomalous, I’m going to extrapolate that 2021-2024 should be about the same as 2019.

I assume the kids go to public school, but the parents are saving up for college; to make the math simple, I’ll assume the family is saving enough for each kid to graduate from with a four-year degree from a public university, and that saving is spread over 16 years of the child’s life. 2*4/16 = 0.5; this means that each year the family needs to come up with 0.5 years of cost of attendance. (I had to get the last few years from here, but the numbers are comparable.)

I assume the family owns two cars—both working full time, they kinda have to—which I amortize over 10 year lifetimes; 2*1/10 = 0.2, so each year the family pays 0.2 times the value of an average midsize car. (The current average new car price is $33226; I then use the CPI for cars to figure out what it was in previous years.)

I assume they pay a 30-year mortgage on the median home; they would pay interest on this mortgage, so I need to factor that in. I’ll assume they pay the average mortgage rate in that year, but I don’t want to have to do a full mortgage calculation (including PMI, points, down payment etc.) for each year, so I’ll say that they amount they pay is (1/30 + 0.5 (interest rate))*(home value) per year, which seems to be a reasonable approximation over the relevant range.

I assume that both adults have a 15-mile commute (this seems roughly commensurate with the current mean commute time of 26 minutes), both adults work 5 days per week, 50 weeks per year, and their cars get the median level of gas mileage. This means that they consume 2*15*2*5*50/(median MPG) = 15000/(median MPG) gallons of gasoline per year. I’ll use this BTS data for gas mileage. I’m intentionally not using median gasoline consumption, because when gas is cheap, people might take more road trips, which is consumption that could be avoided without great hardship when gas gets expensive. I will also assume that the kids take the bus to school, so that doesn’t contribute to the gasoline cost.

That I will multiply by the average price of gasoline in June of that year, which I have from the EIA since 1993. (I’ll extrapolate 1990-1992 as the same as 1993, which is conservative.)

I will assume that the family owns 2 cell phones, 1 computer, and 1 television. This is tricky, because the quality of these tech items has dramatically increased over time.

If you try to measure with equivalent buying power (e.g. a 1 MHz computer, a 20-inch CRT TV), then you’ll find that these items have gotten radically cheaper; $1000 in 1950 would only buy as much TV as $7 today, and a $50 Raspberry Pi‘s 2.4 GHz processor is 150 times faster than the 16 MHz offered by an Apple Powerbook in 1991—despite the latter selling for $2500 nominally. So in dollars per gigahertz, the price of computers has fallen by an astonishing 7,500 times just since 1990.

But I think that’s an unrealistic comparison. The standards for what was considered necessary have also increased over time. I actually think it’s quite fair to assume that people have spent a roughly constant nominal amount on these items: about $500 for a TV, $1000 for a computer, and $500 for a cell phone. I’ll also assume that the TV and phones are good for 5 years while the computer is good for 2 years, which makes the total annual expenditure for 2 phones, a TV, and a computer equal to 2/5*500 + 1/5*500 + 1/2*1000 = 800. This is about what a family must spend every year to feel like they have an adequate amount of digital technology.

I will also assume that the family buys clothes with this equivalent purchasing power, with an index that goes from 166 in 1990 to 177 in 2024—also nearly constant in nominal terms. I’ll multiply that index by $10 because the average annual household spending on clothes is about $1700 today.

I will assume that the family buys the equivalent of five months of infant care per year; they surely spend more than this (in either time or money) when they have actual infants, but less as the kids grow. This amounts to about $5000 today, but was only $1600 in 1990—a 214% increase, or 3.42% per year.

For food expenditure, I’m going to use the USDA’s thrifty plan for June of that year. I’ll use the figures assuming that one child is 6 and the other is 9. I don’t have data before 1994, so I’ll extrapolate that with the average growth rate of 3.2%.

Food expenditures have been at a fairly consistent 11% of disposable income since 1990; so I’m going to include them as 2*11%*40*50*(after-tax median wage) = 440*(after-tax median wage).

The figures I had the hardest time getting were for utilities. It’s also difficult to know what to include: Is Internet access a necessity? Probably, nowadays—but not in 1990. Should I separate electric and natural gas, even though they are partial substitutes? But using these figures I estimate that utility costs rise at about 0.8% per year in CPI-adjusted terms, so what I’ll do is benchmark to $3800 in 2016 and assume that utility costs have risen by (0.8% + inflation rate) per year each year.

Healthcare is also a tough one; pardon the heteronormativity, but for simplicity I’m going to use the mean personal healthcare expenditures for one man and woman (aged 19-44) and one boy and one girl (aged 0-18). Unfortunately I was only able to find that for two-year intervals in the range from 2002 to 2020, so I interpolated and extrapolated both directions assuming the same average growth rate of 3.5%.

So let’s summarize what all is included here:

- Estimated payment on a mortgage

- 0.5 years of college tuition

- amortized cost of 2 cars

- 7500/(median MPG) gallons of gasoline

- amortized cost of 2 phones, 1 computer, and 1 television

- average spending on clothes

- 11% of income on food

- Estimated utilities spending

- Estimated childcare equivalent to five months of infant care

- Healthcare for one man, one woman, one boy, one girl

There are obviously many criticisms you could make of these choices. If I were writing a proper paper, I would search harder for better data and run robustness checks over the various estimation and extrapolation assumptions. But for these purposes I really just want a ballpark figure, something that will give me a sense of what rising cost of living feels like to most people.

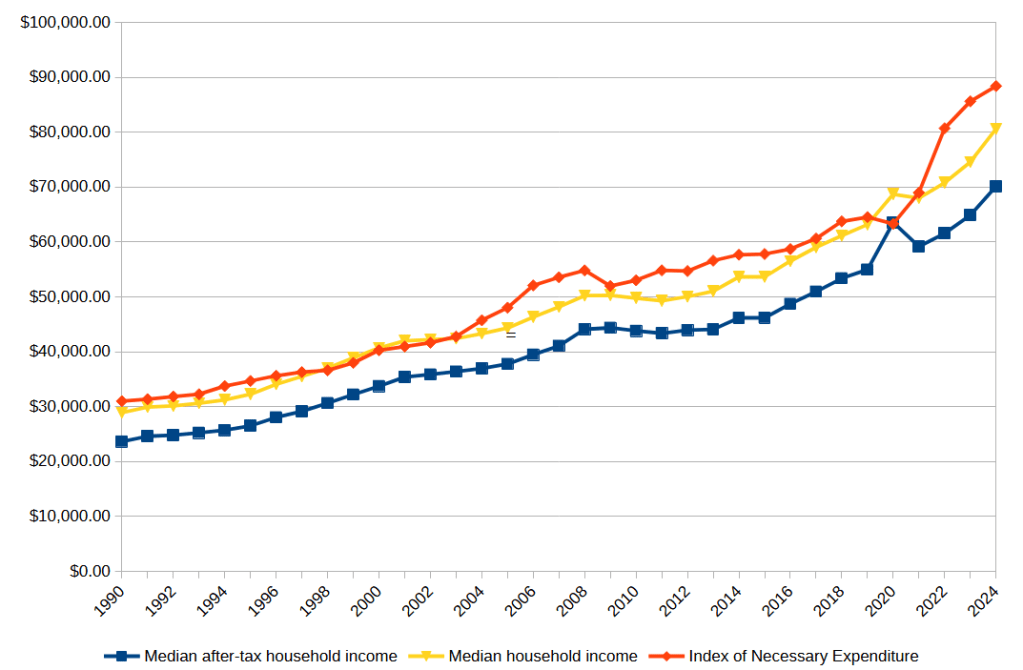

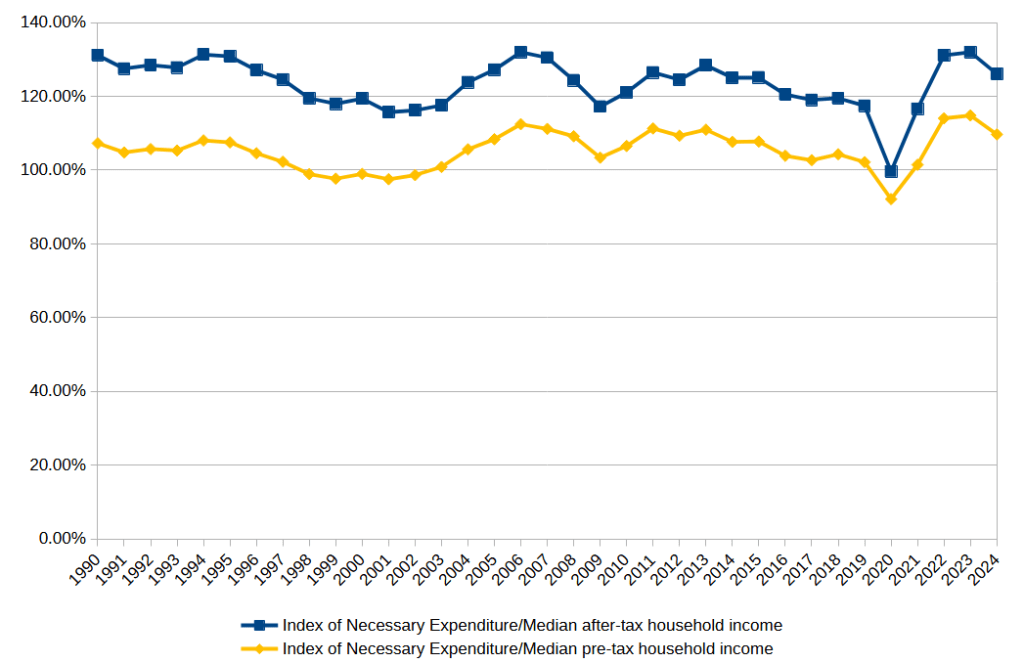

What I found absolutely floored me. Over the range from 1990 to 2024:

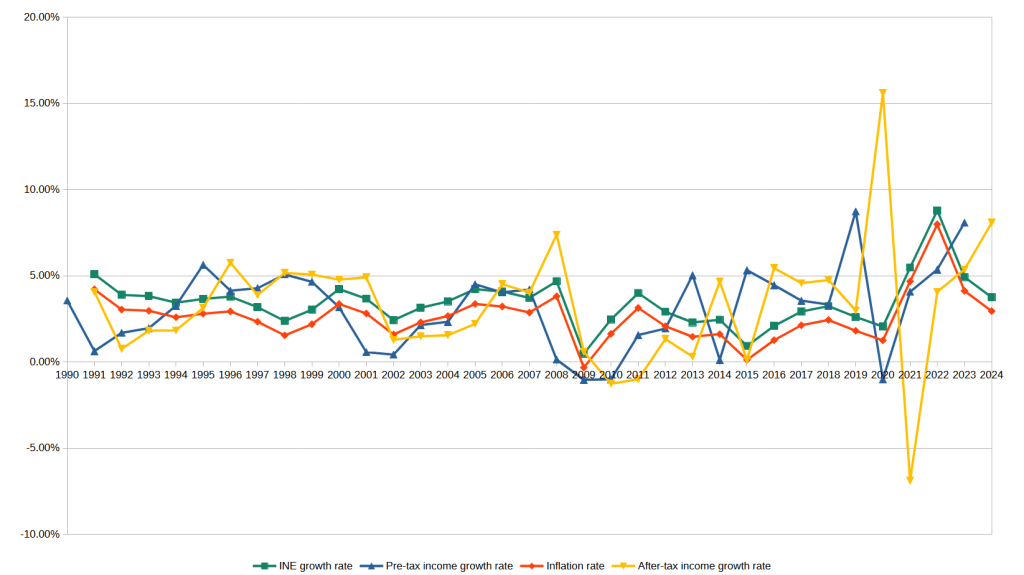

- The Index of Necessary Expenditure rose by an average of 3.45% per year, almost a full percentage point higher than the average CPI inflation of 2.62% per year.

- Over the same period, after-tax income rose at a rate of 3.31%, faster than CPI inflation, but slightly slower than the growth rate of INE.

- The Index of Necessary Expenditure was over 100% of median after-tax household income every year except 2020.

- Since 2021, the Index of Necessary Expenditure has risen at an average rate of 5.74%, compared to CPI inflation of only 2.66%. In that same time, after-tax income has only grown at a rate of 4.94%.

Point 3 is the one that really stunned me. The only time in the last 34 years that a family of four has been able to actually pay for all necessities—just necessities—on a typical household income was during the COVID pandemic, and that in turn was only because the federal tax burden had been radically reduced in response to the crisis. This means that every single year, a typical American family has been either going further and further into debt, or scrimping on something really important—like healthcare or education.

No wonder people feel like the economy is failing them! It is!

In fact, I can even make sense now of how Trump could convince people with “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” in 2024 looking back at 2020—while the pandemic was horrific and the disruption to the economy was massive, thanks to the US government finally actually being generous to its citizens for once, people could just about actually make ends meet. That one year. In my entire life.

This is why people felt betrayed by Biden’s economy. For the first time most of us could remember, we actually had this brief moment when we could pay for everything we needed and still have money left over. And then, when things went back to “normal”, it was taken away from us. We were back to no longer making ends meet.

When I went into this, I expected to see that the INE had risen faster than both inflation and income, which was indeed the case. But I expected to find that INE was a large but manageable proportion of household income—maybe 70% or 80%—and slowly growing. Instead, I found that INE was greater than 100% of income in every year but one.

And the truth is, I’m not sure I’ve adequately covered all necessary spending! My figures for childcare and utilities are the most uncertain; those could easily go up or down by quite a bit. But even if I exclude them completely, the reduced INE is still greater than income in most years.

Suddenly the way people feel about the economy makes a lot more sense to me.