Jun 18 JDN 2460114

A review of The Darker Angels of Our Nature

(I apologize for not releasing this on Sunday; I’ve been traveling lately and haven’t found much time to write.)

Since its release, I have considered Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of our Nature among a small elite category of truly great books—not simply good because enjoyable, informative, or well-written, but great in its potential impact on humanity’s future. Others include The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, On the Origin of Species, and Animal Liberation.

But I also try to expose myself as much as I can to alternative views. I am quite fearful of the echo chambers that social media puts us in, where dissent is quietly hidden from view and groupthink prevails.

So when I saw that a group of historians had written a scathing critique of The Better Angels, I decided I surely must read it and get its point of view. This book is The Darker Angels of Our Nature.

The Darker Angels is written by a large number of different historians, and it shows. It’s an extremely disjointed book; it does not present any particular overall argument, various sections differ wildly in scope and tone, and sometimes they even contradict each other. It really isn’t a book in the usual sense; it’s a collection of essays whose only common theme is that they disagree with Steven Pinker.

In fact, even that isn’t quite true, as some of the best essays in The Darker Angels are actually the ones that don’t fundamentally challenge Pinker’s contention that global violence has been on a long-term decline for centuries and is now near its lowest in human history. These essays instead offer interesting insights into particular historical eras, such as medieval Europe, early modern Russia, and shogunate Japan, or they add additional nuances to the overall pattern, like the fact that, compared to medieval times, violence in Europe seems to have been less in the Pax Romana (before) and greater in the early modern period (after), showing that the decline in violence was not simple or steady, but went through fluctuations and reversals as societies and institutions changed. (At this point I feel I should note that Pinker clearly would not disagree with this—several of the authors seem to think he would, which makes me wonder if they even read The Better Angels.)

Others point out that the scale of civilization seems to matter, that more is different, and larger societies and armies more or less automatically seem to result in lower fatality rates by some sort of scaling or centralization effect, almost like the square-cube law. That’s very interesting if true; it would suggest that in order to reduce violence, you don’t really need any particular mode of government, you just need something that unites as many people as possible under one banner. The evidence presented for it was too weak for me to say whether it’s really true, however, and there was really no theoretical mechanism proposed whatsoever.

Some of the essays correct genuine errors Pinker made, some of which look rather sloppy. Pinker clearly overestimated the death tolls of the An Lushan Rebellion, the Spanish Inquisition, and Aztec ritual executions, probably by using outdated or biased sources. (Though they were all still extremely violent!) His depiction of indigenous cultures does paint with a very broad brush, and fails to recognize that some indigenous societies seem to have been quite peaceful (though others absolutely were tremendously violent).

One of the best essays is about Pinker’s cavalier attitude toward mass incarceration, which I absolutely do consider a deep flaw in Pinker’s view. Pinker presents increased incarceration rates along with decreased crime rates as if they were an unalloyed good, while I can at best be ambivalent about whether the benefit of decreasing crime is worth the cost of greater incarceration. Pinker seems to take for granted that these incarcerations are fair and impartial, when we have a great deal of evidence that they are strongly biased against poor people and people of color.

There’s another good essay about the Enlightenment, which Pinker seems to idealize a little too much (especially in his other book Enlightenment Now). There was no sudden triumph of reason that instantly changed the world. Human knowledge and rationality gradually improved over a very long period of time, with no obvious turning point and many cases of backsliding. The scientific method isn’t a simple, infallible algorithm that suddenly appeared in the brain of Galileo or Bayes, but a whole constellation of methods and concepts of rationality that took centuries to develop and is in fact still developing. (Much as the Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao, the scientific method that can be written in a textbook is not the true scientific method.)

Several of the essays point out the limitations of historical and (especially) archaeological records, making it difficult to draw any useful inferences about rates of violence in the past. I agree that Pinker seems a little too cavalier about this; the records really are quite sparse and it’s not easy to fill in the gaps. Very small samples can easily distort homicide rates; since only about 1% of deaths worldwide are homicide, if you find 20 bodies, whether or not one of them was murdered is the difference between peaceful Japan and war-torn Colombia.

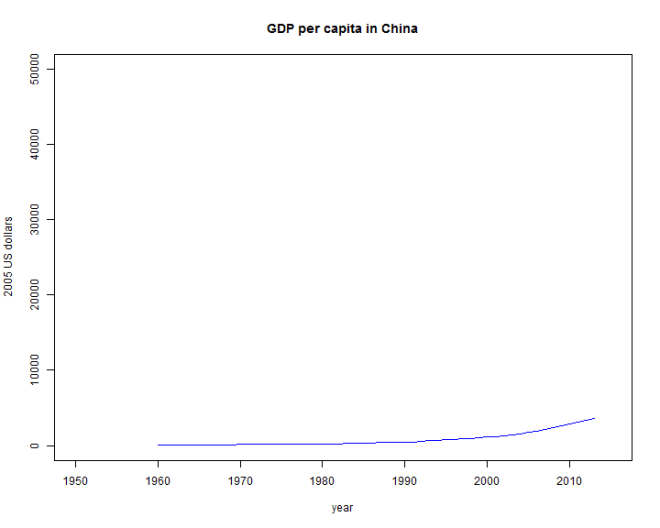

On the other hand, all we really can do is make the best inferences we have with the available data, and for the time periods in which we do have detailed records—surely true since at least the 19th century—the pattern of declining violence is very clear, and even the World Wars look like brief fluctuations rather than fundamental reversals. Contrary to popular belief, the World Wars do not appear to have been especially deadly on a per-capita basis, compared to various historic wars. The primary reason so many people died in the World Wars was really that there just were more people in the world. A few of the authors don’t seem to consider this an adequate reason, but ask yourself this: Would you rather live in a society of 100 in which 10 people are killed, or a society of 1 billion in which 1 million are killed? In the former case your chances of being killed are 10%; in the latter, 0.1%. Clearly, per-capita measures of violence are the correct ones.

Some essays seem a bit beside the point, like one on “environmental violence” which quite aptly details the ongoing—terrifying—degradation of our global ecology, but somehow seems to think that this constitutes violence when it obviously doesn’t. There is widespread violence against animals, certainly; slaughterhouses are the obvious example—and unlike most people, I do not consider them some kind of exception we can simply ignore. We do in fact accept levels of cruelty to pigs and cows that we would never accept against dogs or horses—even the law makes such exceptions. Moreover, plenty of habitat destruction is accompanied by killing of the animals who lived in that habitat. But ecological degradation is not equivalent to violence. (Nor is it clear to me that our treatment of animals is more violent overall today than in the past; I guess life is probably worse for a beef cow today than it was in the medieval era, but either way, she was going to be killed and eaten. And at least we no longer do cat-burning.) Drilling for oil can be harmful, but it is not violent. We can acknowledge that life is more peaceful now than in the past without claiming that everything is better now—in fact, one could even say that overall life isn’t better, but I think they’d be hard-pressed to argue that.

These are the relatively good essays, which correct minor errors or add interesting nuances. There are also some really awful essays in the mix.

A common theme of several of the essays seems to be “there are still bad things, so we can’t say anything is getting better”; they will point out various forms of violence that undeniably still exist, and treat this as a conclusive argument against the claim that violence has declined. Yes, modern slavery does exist, and it is a very serious problem; but it clearly is not the same kind of atrocity that the Atlantic slave trade was. Yes, there are still murders. Yes, there are still wars. Probably these things will always be with us to some extent; but there is a very clear difference between 500 homicides per million people per year and 50—and it would be better still if we could bring it down to 5.

There’s one essay about sexual violence that doesn’t present any evidence whatsoever to contradict the claim that rates of sexual violence have been declining while rates of reporting and prosecution have been increasing. (These two trends together often result in reported rapes going up, but most experts agree that actual rapes are going down.) The entire essay is based on anecdote, innuendo, and righteous anger.

There are several essays that spend their whole time denouncing neoliberal capitalism (not even presenting any particularly good arguments against it, though such arguments do exist), seeming to equate Pinker’s view with some kind of Rothbardian anarcho-capitalism when in fact Pinker is explictly in favor of Nordic-style social democracy. (One literally dismisses his support for universal healthcare as “Well, he is Canadian”.) But Pinker has on occasion said good things about capitalism, so clearly, he is an irredeemable monster.

Right in the introduction—which almost made me put the book down—is an astonishingly ludicrous argument, which I must quote in full to show you that it is not out of context:

What actually is violence (nowhere posed or answered in The Better Angels)? How do people perceive it in different time-place settings? What is its purpose and function? What were contemporary attitudes toward violence and how did sensibilities shift over time? Is violence always ‘bad’ or can there be ‘good’ violence, violence that is regenerative and creative?

The Darker Angels of Our Nature, p.16

Yes, the scare quotes on ‘good’ and ‘bad’ are in the original. (Also the baffling jargon “time-place settings” as opposed to, say, “times and places”.) This was clearly written by a moral relativist. Aside from questioning whether we can say anything about anything, the argument seems to be that Pinker’s argument is invalid because he didn’t precisely define every single relevant concept, even though it’s honestly pretty obvious what the world “violence” means and how he is using it. (If anything, it’s these authors who don’t seem to understand what the word means; they keep calling things “violence” that are indeed bad, but obviously aren’t violence—like pollution and cyberbullying. At least talk of incarceration as “structural violence” isn’t obvious nonsense—though it is still clearly distinct from murder rates.)

But it was by reading the worst essays that I think I gained the most insight into what this debate is really about. Several of the essays in The Darker Angels thoroughly and unquestioningly share the following inference: if a culture is superior, then that culture has a right to impose itself on others by force. On this, they seem to agree with the imperialists: If you’re better, that gives you a right to dominate everyone else. They rightly reject the claim that cultures have a right to imperialistically dominate others, but they cannot deny the inference, and so they are forced to deny that any culture can ever be superior to another. The result is that they tie themselves in knots trying to justify how greater wealth, greater happiness, less violence, and babies not dying aren’t actually good things. They end up talking nonsense about “violence that is regenerative and creative”.

But we can believe in civilization without believing in colonialism. And indeed that is precisely what I (along with Pinker) believe: That democracy is better than autocracy, that free speech is better than censorship, that health is better than illness, that prosperity is better than poverty, that peace is better than war—and therefore that Western civilization is doing a better job than the rest. I do not believe that this justifies the long history of Western colonial imperialism. Governing your own country well doesn’t give you the right to invade and dominate other countries. Indeed, part of what makes colonial imperialism so terrible is that it makes a mockery of the very ideals of peace, justice, and freedom that the West is supposed to represent.

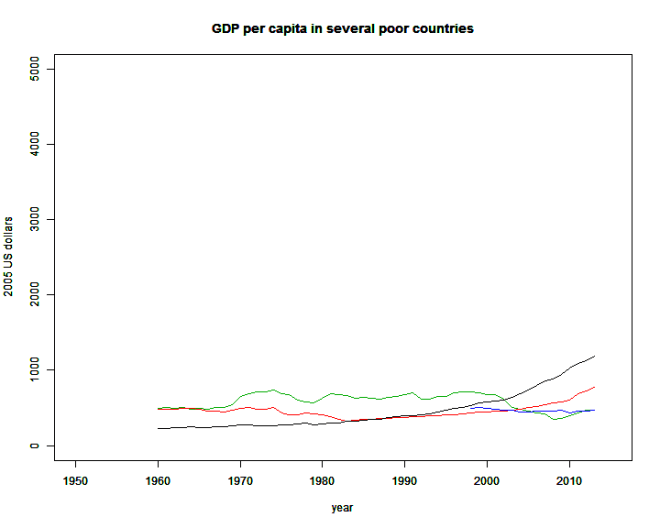

I think part of the problem is that many people see the world in zero-sum terms, and believe that the West’s prosperity could only be purchased by the rest of the world’s poverty. But this is untrue. The world is nonzero-sum. My happiness does not come from your sadness, and my wealth does not come from your poverty. In fact, even the West was poor for most of history, and we are far more prosperous now that we have largely abandoned colonial imperialism than we ever were in imperialism’s heyday. (I do occasionally encounter British people who seem vaguely nostalgic for the days of the empire, but real median income in the UK has doubled just since 1977. Inequality has also increased during that time, which is definitely a problem; but the UK is undeniably richer now than it ever was at the peak of the empire.)

In fact it could be that the West is richer now because of colonalism than it would have been without it. I don’t know whether or not this is true. I suspect it isn’t, but I really don’t know for sure. My guess would be that colonized countries are poorer, but colonizer countries are not richer—that is, colonialism is purely destructive. Certain individuals clearly got richer by such depredation (Leopold II, anyone?), but I’m not convinced many countries did.

Yet even if colonialism did make the West richer, it clearly cannot explain most of the wealth of Western civilization—for that wealth simply did not exist in the world before. All these bridges and power plants, laptops and airplanes weren’t lying around waiting to be stolen. Surely, some of the ingredients were stolen—not least, the land. Had they been bought at fair prices, the result might have been less wealth for us (then again it might not, for wealthier trade partners yield greater exports). But this does not mean that the products themselves constitute theft, nor that the wealth they provide is meaningless. Perhaps we should find some way to pay reparations; undeniably, we should work toward greater justice in the future. But we do not need to give up all we have in order to achieve that justice.

There is a law of conservation of energy. It is impossible to create energy in one place without removing it from another. There is no law of conservation of prosperity. Making the world better in one place does not require making it worse in another.

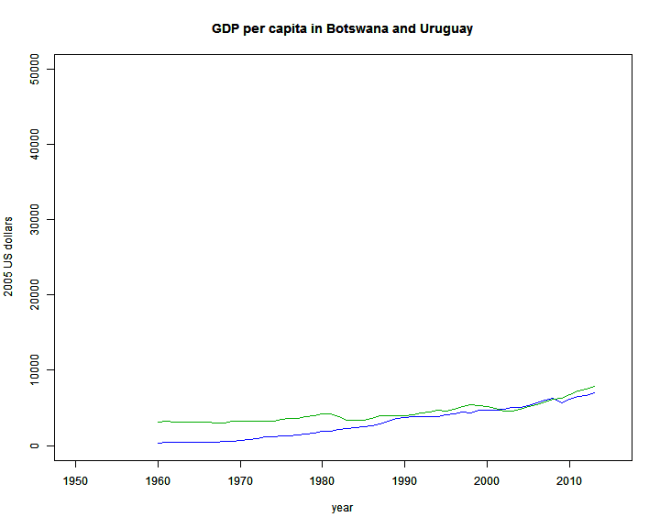

Progress is real. Yes, it is flawed, uneven, and it has costs of its own; but it is real. If we want to have more of it, we best continue to believe in it. And The Better Angels of Our Nature does have some notable flaws, but it still retains its place among truly great books.