JDN 2457166 EDT 17:53.

I just got back from watching Tomorrowland, which is oddly appropriate since I had already planned this topic in advance. How do we, as they say in the film, “fix the world”?

I can’t find it at the moment, but I vaguely remember some radio segment on which a couple of neoclassical economists were interviewed and asked what sort of career can change the world, and they answered something like, “Go into finance, make a lot of money, and then donate it to charity.”

In a slightly more nuanced form this strategy is called earning to give, and frankly I think it’s pretty awful. Most of the damage that is done to the world is done in the name of maximizing profits, and basically what you end up doing is stealing people’s money and then claiming you are a great altruist for giving some of it back. I guess if you can make enormous amounts of money doing something that isn’t inherently bad and then donate that—like what Bill Gates did—it seems better. But realistically your potential income is probably not actually raised that much by working in finance, sales, or oil production; you could have made the same income as a college professor or a software engineer and not be actively stripping the world of its prosperity. If we actually had the sort of ideal policies that would internalize all externalities, this dilemma wouldn’t arise; but we’re nowhere near that, and if we did have that system, the only billionaires would be Nobel laureate scientists. Albert Einstein was a million times more productive than the average person. Steve Jobs was just a million times luckier. Even then, there is the very serious question of whether it makes sense to give all the fruits of genius to the geniuses themselves, who very quickly find they have all they need while others starve. It was certainly Jonas Salk’s view that his work should only profit him modestly and its benefits should be shared with as many people as possible. So really, in an ideal world there might be no billionaires at all.

Here I would like to present an alternative. If you are an intelligent, hard-working person with a lot of talent and the dream of changing the world, what should you be doing with your time? I’ve given this a great deal of thought in planning my own life, and here are the criteria I came up with:

- You must be willing and able to commit to doing it despite great obstacles. This is another reason why earning to give doesn’t actually make sense; your heart (or rather, limbic system) won’t be in it. You’ll be miserable, you’ll become discouraged and demoralized by obstacles, and others will surpass you. In principle Wall Street quantitative analysts who make $10 million a year could donate 90% to UNICEF, but they don’t, and you know why? Because the kind of person who is willing and able to exploit and backstab their way to that position is the kind of person who doesn’t give money to UNICEF.

- There must be important tasks to be achieved in that discipline. This one is relatively easy to satisfy; I’ll give you a list in a moment of things that could be contributed by a wide variety of fields. Still, it does place some limitations: For one, it rules out the simplest form of earning to give (a more nuanced form might cause you to choose quantum physics over social work because it pays better and is just as productive—but you’re not simply maximizing income to donate). For another, it rules out routine, ordinary jobs that the world needs but don’t make significant breakthroughs. The world needs truck drivers (until robot trucks take off), but there will never be a great world-changing truck driver, because even the world’s greatest truck driver can only carry so much stuff so fast. There are no world-famous secretaries or plumbers. People like to say that these sorts of jobs “change the world in their own way”, which is a nice sentiment, but ultimately it just doesn’t get things done. We didn’t lift ourselves into the Industrial Age by people being really fantastic blacksmiths; we did it by inventing machines that make blacksmiths obsolete. We didn’t rise to the Information Age by people being really good slide-rule calculators; we did it by inventing computers that work a million times as fast as any slide-rule. Maybe not everyone can have this kind of grand world-changing impact; and I certainly agree that you shouldn’t have to in order to live a good life in peace and happiness. But if that’s what you’re hoping to do with your life, there are certain professions that give you a chance of doing so—and certain professions that don’t.

- The important tasks must be currently underinvested. There are a lot of very big problems that many people are already working on. If you work on the problems that are trendy, the ones everyone is talking about, your marginal contribution may be very small. On the other hand, you can’t just pick problems at random; many problems are not invested in precisely because they aren’t that important. You need to find problems people aren’t working on but should be—problems that should be the focus of our attention but for one reason or another get ignored. A good example here is to work on pancreatic cancer instead of breast cancer; breast cancer research is drowning in money and really doesn’t need any more; pancreatic cancer kills 2/3 as many people but receives less than 1/6 as much funding. If you want to do cancer research, you should probably be doing pancreatic cancer.

- You must have something about you that gives you a comparative—and preferably, absolute—advantage in that field. This is the hardest one to achieve, and it is in fact the reason why most people can’t make world-changing breakthroughs. It is in fact so hard to achieve that it’s difficult to even say you have until you’ve already done something world-changing. You must have something special about you that lets you achieve what others have failed. You must be one of the best in the world. Even as you stand on the shoulders of giants, you must see further—for millions of others stand on those same shoulders and see nothing. If you believe that you have what it takes, you will be called arrogant and naïve; and in many cases you will be. But in a few cases—maybe 1 in 100, maybe even 1 in 1000, you’ll actually be right. Not everyone who believes they can change the world does so, but everyone who changes the world believed they could.

Now, what sort of careers might satisfy all these requirements?

Well, basically any kind of scientific research:

Mathematicians could work on network theory, or nonlinear dynamics (the first step: separating “nonlinear dynamics” into the dozen or so subfields it should actually comprise—as has been remarked, “nonlinear” is a bit like “non-elephant”), or data processing algorithms for our ever-growing morasses of unprocessed computer data.

Physicists could be working on fusion power, or ways to neutralize radioactive waste, or fundamental physics that could one day unlock technologies as exotic as teleportation and faster-than-light travel. They could work on quantum encryption and quantum computing. Or if those are still too applied for your taste, you could work in cosmology and seek to answer some of the deepest, most fundamental questions in human existence.

Chemists could be working on stronger or cheaper materials for infrastructure—the extreme example being space elevators—or technologies to clean up landfills and oceanic pollution. They could work on improved batteries for solar and wind power, or nanotechnology to revolutionize manufacturing.

Biologists could work on any number of diseases, from cancer and diabetes to malaria and antibiotic-resistant tuberculosis. They could work on stem-cell research and regenerative medicine, or genetic engineering and body enhancement, or on gerontology and age reversal. Biology is a field with so many important unsolved problems that if you have the stomach for it and the interest in some biological problem, you can’t really go wrong.

Electrical engineers can obviously work on improving the power and performance of computer systems, though I think over the last 20 years or so the marginal benefits of that kind of research have begun to wane. Efforts might be better spent in cybernetics, control systems, or network theory, where considerably more is left uncharted; or in artificial intelligence, where computing power is only the first step.

Mechanical engineers could work on making vehicles safer and cheaper, or building reusable spacecraft, or designing self-constructing or self-repairing infrastructure. They could work on 3D printing and just-in-time manufacturing, scaling it up for whole factories and down for home appliances.

Aerospace engineers could link the world with hypersonic travel, build satellites to provide Internet service to the farthest reaches of the globe, or create interplanetary rockets to colonize Mars and the moons of Jupiter and Saturn. They could mine asteroids and make previously rare metals ubiquitous. They could build aerial drones for delivery of goods and revolutionize logistics.

Agronomists could work on sustainable farming methods (hint: stop farming meat), invent new strains of crops that are hardier against pests, more nutritious, or higher-yielding; on the other hand a lot of this is already being done, so maybe it’s time to think outside the box and consider what we might do to make our food system more robust against climate change or other catastrophes.

Ecologists will obviously be working on predicting and mitigating the effects of global climate change, but there are a wide variety of ways of doing so. You could focus on ocean acidification, or on desertification, or on fishery depletion, or on carbon emissions. You could work on getting the climate models so precise that they become completely undeniable to anyone but the most dogmatically opposed. You could focus on endangered species and habitat disruption. Ecology is in general so underfunded and undersupported that basically anything you could do in ecology would be beneficial.

Neuroscientists have plenty of things to do as well: Understanding vision, memory, motor control, facial recognition, emotion, decision-making and so on. But one topic in particular is lacking in researchers, and that is the fundamental Hard Problem of consciousness. This one is going to be an uphill battle, and will require a special level of tenacity and perseverance. The problem is so poorly understood it’s difficult to even state clearly, let alone solve. But if you could do it—if you could even make a significant step toward it—it could literally be the greatest achievement in the history of humanity. It is one of the fundamental questions of our existence, the very thing that separates us from inanimate matter, the very thing that makes questions possible in the first place. Understand consciousness and you understand the very thing that makes us human. That achievement is so enormous that it seems almost petty to point out that the revolutionary effects of artificial intelligence would also fall into your lap.

The arts and humanities also have a great deal to contribute, and are woefully underappreciated.

Artists, authors, and musicians all have the potential to make us rethink our place in the world, reconsider and reimagine what we believe and strive for. If physics and engineering can make us better at winning wars, art and literature and remind us why we should never fight them in the first place. The greatest works of art can remind us of our shared humanity, link us all together in a grander civilization that transcends the petty boundaries of culture, geography, or religion. Art can also be timeless in a way nothing else can; most of Aristotle’s science is long-since refuted, but even the Great Pyramid thousands of years before him continues to awe us. (Aristotle is about equidistant chronologically between us and the Great Pyramid.)

Philosophers may not seem like they have much to add—and to be fair, a great deal of what goes on today in metaethics and epistemology doesn’t add much to civilization—but in fact it was Enlightenment philosophy that brought us democracy, the scientific method, and market economics. Today there are still major unsolved problems in ethics—particularly bioethics—that are in need of philosophical research. Technologies like nanotechnology and genetic engineering offer us the promise of enormous benefits, but also the risk of enormous harms; we need philosophers to help us decide how to use these technologies to make our lives better instead of worse. We need to know where to draw the lines between life and death, between justice and cruelty. Literally nothing could be more important than knowing right from wrong.

Now that I have sung the praises of the natural sciences and the humanities, let me now explain why I am a social scientist, and why you probably should be as well.

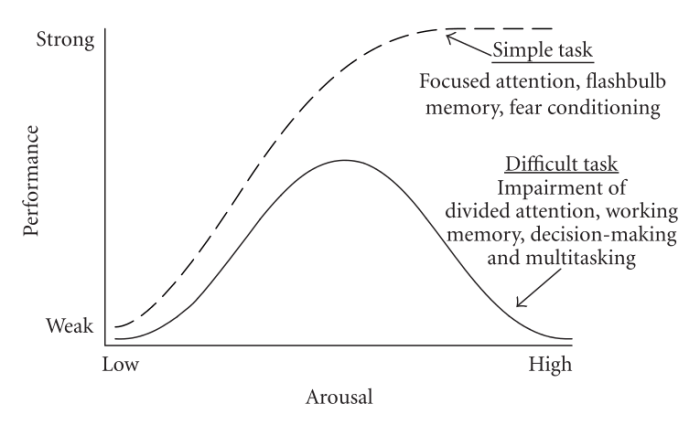

Psychologists and cognitive scientists obviously have a great deal to give us in the study of mental illness, but they may actually have more to contribute in the study of mental health—in understanding not just what makes us depressed or schizophrenic, but what makes us happy or intelligent. The 21st century may not simply see the end of mental illness, but the rise of a new level of mental prosperity, where being happy, focused, and motivated are matters of course. The revolution that biology has brought to our lives may pale in comparison to the revolution that psychology will bring. On the more social side of things, psychology may allow us to understand nationalism, sectarianism, and the tribal instinct in general, and allow us to finally learn to undermine fanaticism, encourage critical thought, and make people more rational. The benefits of this are almost impossible to overstate: It is our own limited, broken, 90%-or-so heuristic rationality that has brought us from simians to Shakespeare, from gorillas to Godel. To raise that figure to 95% or 99% or 99.9% could be as revolutionary as was whatever evolutionary change first brought us out of the savannah as Australopithecus africanus.

Sociologists and anthropologists will also have a great deal to contribute to this process, as they approach the tribal instinct from the top down. They may be able to tell us how nations are formed and undermined, why some cultures assimilate and others collide. They can work to understand combat bigotry in all its forms, racism, sexism, ethnocentrism. These could be the fields that finally end war, by understanding and correcting the imbalances in human societies that give rise to violent conflict.

Political scientists and public policy researchers can allow us to understand and restructure governments, undermining corruption, reducing inequality, making voting systems more expressive and more transparent. They can search for the keystones of different political systems, finding the weaknesses in democracy to shore up and the weaknesses in autocracy to exploit. They can work toward a true international government, representative of all the world’s people and with the authority and capability to enforce global peace. If the sociologists don’t end war and genocide, perhaps the political scientists can—or more likely they can do it together.

And then, at last, we come to economists. While I certainly work with a lot of ideas from psychology, sociology, and political science, I primarily consider myself an economist. Why is that? Why do I think the most important problems for me—and perhaps everyone—to be working on are fundamentally economic?

Because, above all, economics is broken. The other social sciences are basically on the right track; their theories are still very limited, their models are not very precise, and there are decades of work left to be done, but the core principles upon which they operate are correct. Economics is the field to work in because of criterion 3: Almost all the important problems in economics are underinvested.

Macroeconomics is where we are doing relatively well, and yet the Keynesian models that allowed us to reduce the damage of the Second Depression nonetheless had no power to predict its arrival. While inflation has been at least somewhat tamed, the far worse problem of unemployment has not been resolved or even really understood.

When we get to microeconomics, the neoclassical models are totally defective. Their core assumptions of total rationality and total selfishness are embarrassingly wrong. We have no idea what controls assets prices, or decides credit constraints, or motivates investment decisions. Our models of how people respond to risk are all wrong. We have no formal account of altruism or its limitations. As manufacturing is increasingly automated and work shifts into services, most economic models make no distinction between the two sectors. While finance takes over more and more of our society’s wealth, most formal models of the economy don’t even include a financial sector.

Economic forecasting is no better than chance. The most widely-used asset-pricing model, CAPM, fails completely in empirical tests; its defenders concede this and then have the audacity to declare that it doesn’t matter because the mathematics works. The Black-Scholes derivative-pricing model that caused the Second Depression could easily have been predicted to do so, because it contains a term that assumes normal distributions when we know for a fact that financial markets are fat-tailed; simply put, it claims certain events will never happen that actually occur several times a year.

Worst of all, economics is the field that people listen to. When a psychologist or sociologist says something on television, people say that it sounds interesting and basically ignore it. When an economist says something on television, national policies are shifted accordingly. Austerity exists as national policy in part due to a spreadsheet error by two famous economists.

Keynes already knew this in 1936: “The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.”

Meanwhile, the problems that economics deals with have a direct influence on the lives of millions of people. Bad economics gives us recessions and depressions; it cripples our industries and siphons off wealth to an increasingly corrupt elite. Bad economics literally starves people: It is because of bad economics that there is still such a thing as world hunger. We have enough food, we have the technology to distribute it—but we don’t have the economic policy to lift people out of poverty so that they can afford to buy it. Bad economics is why we don’t have the funding to cure diabetes or colonize Mars (but we have the funding for oil fracking and aircraft carriers, don’t we?). All of that other scientific research that needs done probably could be done, if the resources of our society were properly distributed and utilized.

This combination of both overwhelming influence, overwhelming importance and overwhelming error makes economics the low-hanging fruit; you don’t even have to be particularly brilliant to have better ideas than most economists (though no doubt it helps if you are). Economics is where we have a whole bunch of important questions that are unanswered—or the answers we have are wrong. (As Will Rogers said, “It isn’t what we don’t know that gives us trouble, it’s what we know that ain’t so.”)

Thus, rather than tell you go into finance and earn to give, those economists could simply have said: “You should become an economist. You could hardly do worse than we have.”