May 18 JDN 2460814

These are dark times indeed. ICE is now arresting people without warrants, uniforms or badges and detaining them in camps without lawyers or trials. That is, we now have secret police who are putting people in concentration camps. Don’t mince words here; these are not “arrests” or “deportations”, because those actions would require warrants and due process of law.

Fascism has arrived in America, and, just as predicted, it is indeed wrapped in the flag.

I don’t really have anything to say to console you about this. It’s absolutely horrific, and the endless parade of ever more insane acts and violations of civil rights under Trump’s regime has been seriously detrimental to my own mental health and that of nearly everyone I know.

But there is something I do want to say:

I believe the United States of America is worth saving.

I don’t think we need to burn it all down and start with something new. I think we actually had something pretty good here, and once Trump is finally gone and we manage to fix some of the tremendous damage he has done, I believe that we can put better safeguards in place to stop something like this from happening again.

Of course there are many, many ways that the United States could be made better—even before Trump took the reins and started wrecking everything. But when we consider what we might have had instead, the United States turns out looking a lot better than most of the alternatives.

Is the United States especially evil?

Every nation in the world has darkness in its history. The United States is assuredly no exception: Genocide against Native Americans, slavery, Jim Crow, and the Japanese internment to name a few. (I could easily name many more, but I think you get the point.) This country is certainly responsible for a great deal of evil.

But unlike a lot of people on the left, I don’t think the United States is uniquely or especially evil. In fact, I think we have quite compelling reasons to think that the United States overall has been especially good, and could be again.

How can I say such a thing about a country that has massacred natives, enslaved millions, and launched a staggering number of coups?

Well, here’s the thing:

Every country’s history is like that.

Some are better or worse than others, but it’s basically impossible to find a nation on Earth that hasn’t massacred, enslaved, or conquered another group—and often all three. I guess maybe some of the very youngest countries might count, those that were founded by overthrowing colonial rule within living memory. But certainly those regions and cultures all had similarly dark pasts.

So what actually makes the United States different?

What is distinctive about the United States, relative to other countries? It’s large, it’s wealthy, it’s powerful; that is certainly all true. But other nations and empires have been like that—Rome once was, and China has gained and lost such status multiple times throughout its long history.

Is it especially corrupt? No, its corruption ratings are on a par with other First World countries.

Is it especially unequal? Compared to the rest of the First World, certainly; but by world standards, not really. (The world is a very unequal place.)

But there are two things about the United States that really do seem unique.

The first is how the United States was founded.

Some countries just sort of organically emerged. They were originally tribes that lived in that area since time immemorial, and nobody really knows when they came about; they just sort of happened.

Most countries were created by conquering or overthrowing some other country. Usually one king wanted some territory that was held by another king, so he gathered an army and took over that territory and said it was his now. Or someone who wasn’t a king really wanted to become one, so he killed the current king and took his place on the throne.

And indeed, for most of history, most nations have been some variant of authoritarianism. Monarchy was probably the most common, but there were also various kinds of oligarchy, and sometimes military dictatorship. Even Athens, the oldest recorded “democracy”, was really an oligarchy of Greek male property owners. (Granted, the US also started out pretty much the same way.)

I’m glossing over a huge amount of variation and history here, of course. But what I really want to get at is just how special the founding of the United States was.

The United States of America was the first country on Earth to be designed.

Up until that point, countries just sort of emerged, or they governed however their kings wanted, or they sort of evolved over time as different interest groups jockeyed for control of the oligarchy.

But the Constitution of the United States was something fundamentally new. A bunch of very smart, well-read, well-educated people (okay, mostly White male property owners, with a few exceptions) gathered together to ask the bold question: “What is the best way to run a country?”

And they discussed and argued and debated over this, sometimes finding agreement, other times reaching awkward compromises that no one was really satisfied with. But when the dust finally settled, they had a blueprint for a better kind of nation. And then they built it.

This was a turning point in human history.

Since then, hundreds of constitutions have been written, and most nations on Earth have one of some sort (and many have gone through several). We now think of writing a constitution as what you do to make a country. But before the United States, it wasn’t! A king just took charge and did whatever he wanted! There were no rules; there was no document telling him what he could and couldn’t do.

Most countries for most of history really only had one rule:

Yes, there was some precedent for a constitution, even going all the way back to the Magna Carta; but that wasn’t created when England was founded, it was foisted upon the king after England had already been around for centuries. And it was honestly still pretty limited in how it restricted the king.

Now, it turns out that the Founding Fathers made a lot of mistakes in designing the Constitution; but I think this is quite forgivable, for two reasons:

- They were doing this for the first time. Nobody had ever written a constitution before! Nobody had governed a democracy (even of the White male property-owner oligarchy sort) in centuries!

- They knew they would make mistakes—and they included in the Constitution itself a mechanism for amending it to correct those mistakes.

And amend it we have, 27 times so far, most importantly the Bill of Rights and the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments, which together finally created true universal suffrage—a real democracy. And even in 1920 when the Nineteenth Amendment was passed, this was an extremely rare thing. Many countries had followed the example of the United States by now, but only a handful of them granted voting rights to women.

The United States really was a role model for modern democracy. It showed the world that a nation governed by its own people could be prosperous and powerful.

The second is how the United States expanded its influence.

Many have characterized the United States as an empire, because its influence is so strongly felt around the world. It is undeniably a hegemon, at least.

The US military is the world’s most powerful, accounting for by far the highest spending (more than the next 9 countries combined!) and 20 of the world’s 51 aircraft carriers (China has 5—and they’re much smaller). (The US military is arguably not the largest since China has more soldiers and more ships. But US soldiers are much better trained and equipped, and the US Navy has far greater tonnage.) Most of the world’s currency exchange is done in dollars. Nearly all the world’s air traffic control is done in English. The English-language Internet is by far the largest, forming nearly the majority of all pages by itself. Basically every computer in the world either runs as its operating system Windows, Mac, or Linux—all of which were created in the United States. And since the US attained its hegemony after World War 2, the world has enjoyed a long period of relative peace not seen in centuries, sometimes referred to as the Pax Americana. These all sound like characteristics of an empire.

Yet if it is an empire, the United States is a very unusual one.

Most empires are formed by conquest: Rome created an empire by conquering most of Europe and North Africa. Britain created an empire by colonizing and conquering natives all around the globe.

Yet aside from the Native Americans (which, I admit, is a big thing to discount) and a few other exceptions, the United States engaged in remarkably little conquest. Its influence is felt as surely across the globe as Britain’s was at the height of the British Empire, yet where under Britain all those countries were considered holdings of the Crown (until they all revolted), under the Pax Americana they all have their own autonomous governments, most of them democracies (albeit most of them significantly flawed—including the US itself, these days).

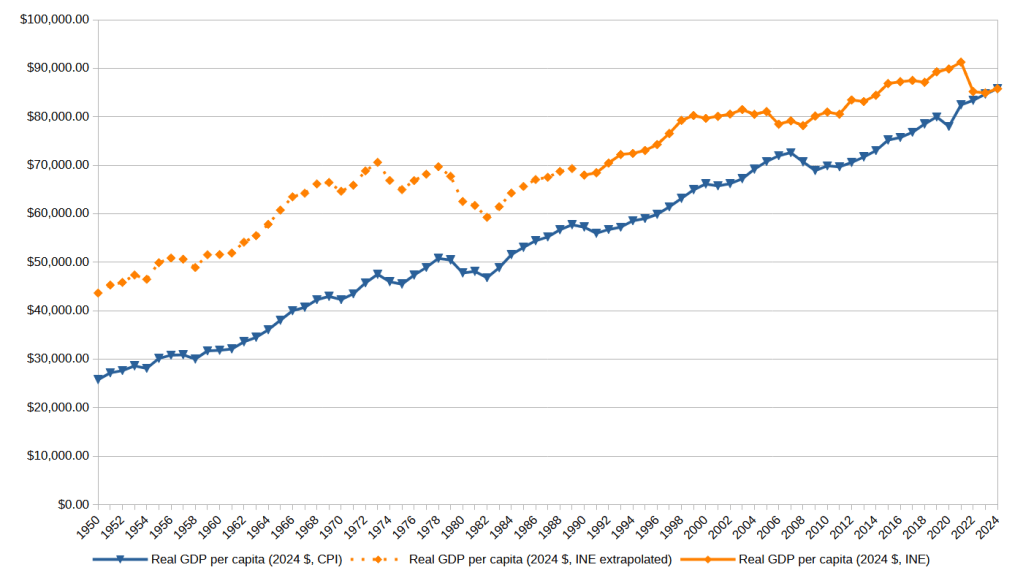

That is, the United States does not primarily spread its influence by conquering other nations. It primarily spreads its influence through diplomacy and trade. Its primary methods are peaceful and mutually-beneficial. And the world has become tremendously wealthier, more peaceful, and all around better off because of this.

Yes, there are some nuances here: The US certainly has engaged in a large number of coups intended to decide what sort of government other countries would have, especially in Latin America. Some of these coups were in favor of democratic governments, which might be justifiable; but many were in favor of authoritarian governments that were simply more capitalist, which is awful. (Then again, while the US was instrumental in supporting authoritarian capitalist regimes in Chile and South Korea, those two countries did ultimately turn into prosperous democracies—especially South Korea.)

So it still remains true that the United States is guilty of many horrible crimes; I’m not disputing that. What I’m saying is that if any other nation had been in its place, things would most like have been worse. This is even true of Britain or France, which are close allies of the US and quite similar; both of these countries, when they had a chance at empire, took it by brutal force. Even Norway once had an empire built by conquest—though I’ll admit, that was a very long time ago.

I admit, it’s depressing that this is what a good nation looks like.

I think part of the reason why so many on the left imagine the United States to be uniquely evil is that they want to think that somewhere out there is a country that’s better than this, a country that doesn’t have staggering amounts of blood on its hands.

But no, this is pretty much as good as it gets. While there are a few countries with a legitimate claim to being better (mostly #ScandinaviaIsBetter), the vast majority of nations on Earth are not better than the United States; they are worse.

Humans have a long history of doing terrible things to other humans. Some say it’s in our nature. Others believe that it is the fault of culture or institutions. Likely both are true to some extent. But if you look closely into the history of just about anywhere on Earth, you will find violence and horror there.

What you won’t always find is a nation that marks a turning point toward global democracy, or a nation that establishes its global hegemony through peaceful and mutually-beneficial means. Those nations are few and far between, and indeed are best exemplified by the United States of America.