Nov 30 JDN 2461010

This post has been written before, but will go live after, Thanksgiving.

Thanksgiving is honestly a very ambivalent holiday.

The particular event it celebrates don’t seem quite so charming in their historical context: Rather than finding peace and harmony with all Native Americans, the Pilgrims in fact allied with the Wampanoag against the Narragansett, though they did later join forces with the Narragansett in order to conquer the Pequot. And of course we all know how things went for most Native American nations in the long run.

Moreover, even the gathering of family comes with some major downsides, especially in a time of extreme political polarization such as this one. I won’t be joining any of my Trump-supporting relatives for dinner this year (and they probably wouldn’t have invited me anyway), but the fact that this means becoming that much more detached from a substantial part of my extended family is itself a tragedy.

This year in particular, US policy has gotten so utterly horrific that it often feels like we have nothing to be thankful for at all, that all we thought was good and just in the world could simply be torn away at a moment’s notice by raving madmen. It isn’t really quite that bad—but it feels that way sometimes.

It also felt a bit uncanny celebrating Thanksgiving a few years ago when we were living in Scotland, for the UK does not celebrate Thanksgiving, but absolutely does celebrate Black Friday: Holidays may be local, but capitalism is global.

But fall feasts of giving thanks are far more ancient than that particular event in 1621 that we have mythologized to oblivion. They appear in numerous cultures across the globe—indeed their very ubiquity may be why the Wampanoag were so willing to share one with the Pilgrims despite their cultures having diverged something like 40,000 years prior.

And I think that it is by seeing ourselves in that context—as part of the whole of humanity—that we can best appreciate what we truly do have to be thankful for, and what we truly do have to look forward to in the future.

Above all, medicine.

We have actual treatments for some diseases, even actual cures for some. By no means all, of course—and it often feels like we are fighting an endless battle even against what we can treat.

But it is worth reflecting on the fact that aside from the last few centuries, this has simply not been the case. There were no actual treatments. There was no real medicine.

Oh, sure, there were attempts at medicine; and there was certainly what we would think of as more like “first aid”: bandaging wounds, setting broken bones. Even amputation and surgery were done sometimes. But most medical treatment was useless or even outright harmful—not least because for most of history, most of it was done without anesthetic or even antiseptic!

There were various herbal remedies for various ailments, some of which even have happened to work: Willow bark genuinely helps with pain, St. John’s wort is a real antidepressant, and some traditional burn creams are surprisingly effective.

But there was no system in place for testing medicine, no way of evaluating what remedies worked and what didn’t. And thus, for every remedy that worked as advertised, there were a hundred more that did absolutely nothing, or even made things worse.

Today, it can feel like we are all chronically ill, because so many of us take so many different pills and supplements. But this is not a sign that we are ill—it is a sign that we can be treated. The pills are new, yes—but the illnesses they treat were here all along.

I don’t see any particular reason to think that Roman plebs or Medieval peasants were any less likely to get migraines than we are; but they certainly didn’t have access to sumatriptan or rimegepant. Maybe they were less likely to get diabetes, but mainly because they were much more likely to be malnourished. (Well, okay, also because they got more exercise, which we surely could stand to.) And they only reason they didn’t get Alzheimer’s was that they usually didn’t live long enough.

Looking further back, before civilization, human health actually does seem to have been better: Foragers were rarely malnourished, weren’t exposed to as many infectious pathogens, and certainly got plenty of exercise. But should a pathogen like smallpox or influenza make it to a forager tribe, the results were often utterly catastrophic.

Today, we don’t really have the sort of plague that human beings used to deal with. We have pandemics, which are also horrible, but far less so. We were horrified by losing 0.3% of our population to COVID; a society that had only suffered 0.3%—or even ten times that, 3%—losses from the Black Death would have been hailed as a miracle, for a more typical rate was 30%.

At 0.3%, most of us knew somebody, or knew somebody who knew somebody, who died from COVID. At 3%, nearly everyone would know somebody, and most would know several. At 30%, nearly everyone would have close family and friends who died.

Then there is infant mortality.

As recently as 1950—this is living memory—the global infant mortality rate was 14.6%. This is about half what it had been historically; for most of human history, roughly a third of all children died between birth and the age of 5.

Today, it is 2.5%.

Where our distant ancestors expected two out of three of their children to survive and our own great-grandparents expected five out of six can now safely expect thirty-nine out of forty to live. This is the difference between “nearly every family has lost a child” and “most families have not lost a child”.

And this is worldwide; in highly-developed countries it’s even better. The US has a relatively high infant mortality rate by the standards of highly-developed countries (indeed, are we even highly-developed, or are we becoming like Saudi Arabia, extremely rich but so unequal that it doesn’t really mean anything to most of our people?). Yet even for us, the infant mortality rate is 0.5%—so we can expect one-hundred-ninety-nine out of two-hundred to survive. This is at the level of “most families don’t even know someone who has lost a child.”

Poverty is a bit harder to measure.

I am increasingly dubious of conventional measures of poverty; ever since compiling my Index of Necessary Expenditure, I am convinced that economists in general, and perhaps US economists in particular, are systematically underestimating the cost of living and thereby underestimating the prevalence of poverty. (I don’t think this is intentional, mind you; I just think it’s a result of using convenient but simplistic measures and not looking too closely into the details.) I think not being able to sustainably afford a roof over your head constitutes being poor—and that applies to a lot of people.

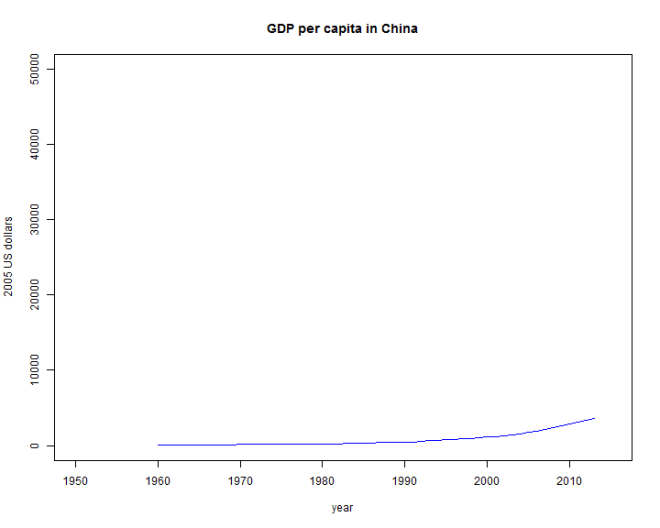

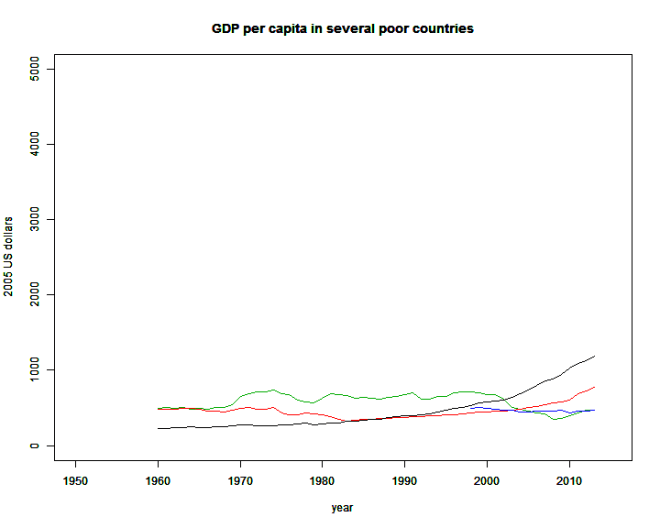

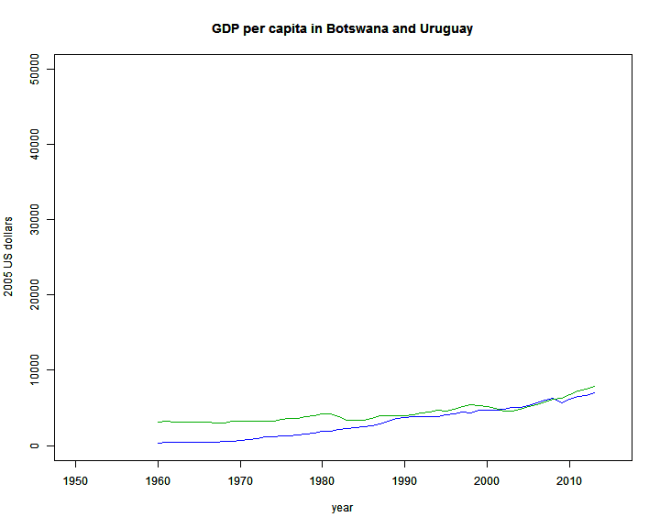

Yet even with that caveat in mind, it’s quite clear that global poverty has greatly declined in the long run.

At the “extreme poverty” level, currently defined as consuming $1.90 at purchasing power parity per day—that’s just under $700 per year, less than 2% of the median personal income in the United States—the number of people has fallen from 1.9 billion in 1990 to about 700 million today. That’s from 36% of the world’s population to under 9% today.

Now, there are good reasons to doubt that “purchasing power parity” really can be estimated as accurately as we would like, and thus it’s not entirely clear that people living on “$2 per day PPP” are really living at less than 2% the standard of living of a typical American (honestly to me that just sounds like… dead); but they are definitely living at a much worse standard of living, and there are a lot fewer people living at such low standard of living today than there used to be not all that long ago. These are people who don’t have reliable food, clean water, or even basic medicine—and that used to include over a third of humanity and does no longer. (And I would like to note that actually finding such a person and giving them a few hundred dollars absolutely would change their life, and this is the sort of thing GiveDirectly does. We may not know exactly how to evaluate their standard of living, but we do know that the actual amount of money they have access to is very, very small.)

There are many ways in which the world could be better than it is.

Indeed, part of the deep, overwhelming outrage I feel pretty much all the time lies in the fact that it would be so easy to make things so much better for so many people, if there weren’t so many psychopaths in charge of everything.

Increased foreign aid is one avenue by which that could be achieved—so, naturally, Trump cut it tremendously. More progressive taxation is another—so, of course, we get tax cuts for the rich.

Just think about the fact that there are families with starving children for whom a $500 check could change their lives; but nobody is writing that check, because Elon Musk needs to become a literal trillionaire.

There are so many water lines and railroad tracks and bridges and hospitals and schools not being built because the money that would have paid for them is tied up in making already unfathomably-rich people even richer.

But even despite all that, things are getting better. Not every day, not every month, not even every year—this past year was genuinely, on net, a bad one. But nearly every decade, every generation, and certainly every century (for at least the last few), humanity has fared better than we did the last.

As long as we can keep that up, we still have much to hope for—and much to be thankful for.