Mar 26, JDN 2457839

Recently President Trump (that phrase may never quite feel right) began presenting his new tax plan. To be honest, it’s not as ridiculous as I had imagined it might be. I mean, it’s still not very good, but it’s probably better than Reagan’s tax plan his last year in office, and it’s not nearly as absurd as the half-baked plan Trump originally proposed during the campaign.

But it got me thinking about the incredible untapped potential of our tax system—the things we could achieve as a nation, if we were willing to really commit to them and raise taxes accordingly.

A few years back I proposed a progressive tax system based upon logarithmic utility. I now have a catchy name for that tax proposal; I call it the logtax. It depends on two parameters—a poverty level, at which the tax rate goes to zero; and what I like to call a metarate—the fundamental rate that sets all the actual tax rates by the formula.

For the poverty level, I suggest we use the highest 2-household poverty level set by the Department of Health and Human Services: Because of Alaska’s high prices, that’s the Alaska poverty level, and the resulting figure is $20,290—let’s round to $20,000.

I would actually prefer to calculate taxes on an individual basis—I see no reason to incentivize particular household arrangements—but as current taxes are calculated on a household basis, I’m going to use that for now.

The metarate can be varied, and in the plans below I will compare different options for the metarate.

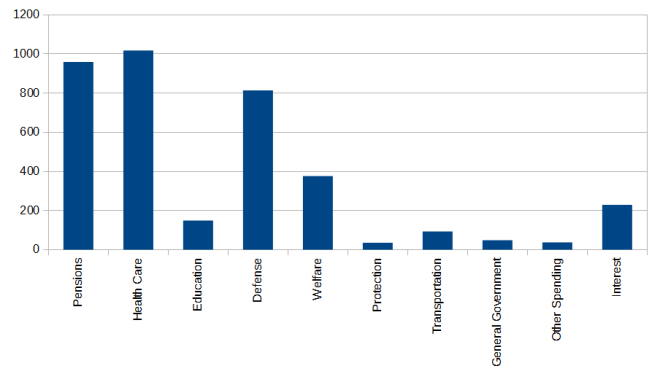

I will compare six different tax plans:

- Our existing tax plan, set under the Obama administration

- Trump’s proposed tax plan

- A flat rate of 30% with a basic income of $12,000, replacing welfare programs and Medicaid

- A flat rate of 40% with a basic income of $15,000, replacing welfare programs and Medicaid

- A logtax with a metarate of 20%, all spending intact

- A logtax with a metarate of 25% and a basic income of $12,000, replacing welfare programs and Medicaid

- A logtax with a metarate of 35% and a basic income of $15,000, cutting military spending by 50% and expanding Medicare to the entire population while eliminating Medicare payroll taxes

To do a proper comparison, I need estimates of the income distribution in the United States, in order to properly estimate the revenue from each type of tax. For that I used US Census data for most of the income data, supplementing with the World Top Incomes database for the very highest income brackets. The household data is broken up into brackets of $5,000 and only goes up to $250,000, so it’s a rough approximation to use the average household income for each bracket, but it’s all I’ve got.

The current brackets are 10%, 15%, 25%, 28%, 33%, 35%, and 39.6%. These are actually marginal rates, not average rates, which makes the calculation a lot more complicated. I did it properly though; for example, when you start paying the marginal rate of 28%, your average rate is really only 20.4%.

Worst of all, I used static scoring—that is, I ignored the Laffer Effect by which increasing taxes changes incentives and can change pre-tax incomes. To really do this analysis properly, one should use dynamic scoring, taking these effects into account—but proper dynamic scoring is an enormous undertaking, and this is a blog post, not my dissertation.

Still, I was able to get pretty close to the true figures. The actual federal budget shows total revenue net of payroll taxes to be $2.397 trillion, whereas I estimated $2.326 trillion; the true deficit is $608 billion and I estimated $682 billion.

Under Trump’s tax plan, almost all rates are cut. He also plans to remove some deductions, but all reports I could find on the plan were vague as to which ones, and with data this coarse it’s very hard to get any good figures on deduction amounts anyway. I also want to give him credit where it’s due: It was a lot easier to calculate the tax rates under Trump’s plan (but still harder than under mine…). But in general what I found was the following:

Almost everyone pays less income tax under Trump’s plan, by generally about 4-5% of their income. The poor benefit less or are slightly harmed; the rich benefit a bit more.

For example, a household in poverty making $12,300 would pay $1,384 currently, but $1,478 under Trump’s plan, losing $94 or 0.8% of their income. An average household making $52,000 would pay $8,768 currently but only $6,238 under Trump’s plan, saving $2,530 or about 4.8% of their income. A household making $152,000 would pay $35,580 currently but only $28,235 under Trump’s plan, saving $7,345 or again about 4.8%. A top 1% household making $781,000 would pay $265,625 currently, but only $230,158 under Trump’s plan, saving $35,467 or about 4.5%. A top 0.1% household making $2,037,000 would pay $762,656 currently, but only $644,350 under Trump’s plan, saving $118,306 or 5.8% of their income. A top 0.01% household making $9,936,000 would pay $3,890,736 currently, but only $3,251,083 under Trump’s plan, saving $639,653 or 6.4% of their income.

Because taxes are cut across the board, Trump’s plan would raise less revenue. My static scoring will exaggerate this effect, but only moderately; my estimate says we would lose over $470 billion in annual revenue, while the true figure might be $300 billion. In any case, Trump will definitely increase the deficit substantially unless he finds a way to cut an awful lot of spending elsewhere—and his pet $54 billion increase to the military isn’t helping in that regard. My estimate of the new deficit under Trump’s plan is $1.155 trillion—definitely not the sort of deficit you should be running during a peacetime economic expansion.

Let’s see what we might have done instead.

If we value simplicity and ease of calculation, it’s hard to beat a flat tax plus basic income. With a flat tax of 30% and a basic income of $12,000 per household, the poor do much better off because of the basic income, while the rich do a little better because of the flat tax, and the middle class feels about the same because the two effects largely cancel. Calculating your tax liability now couldn’t be easier; multiply your income by 3, remove a zero—that’s what you owe in taxes. And how much do you get in basic income? The same as everyone else, $12,000.

Using the same comparison households: The poor household making $12,300 would now receive $8,305—increasing their income by $9,689 or 78.8% relative to the current system. The middle-class household making $52,000 would pay $3,596, saving $5,172 or 10% of their income. The upper-middle-class household making $152,000 would now pay $33,582, saving only $1998 or 1.3% of their income. The top 1% household making $782,000 would pay $234,461, saving $31,164 or 4.0%. The top 0.1% household making $2,037,000 would pay $611,000, saving $151,656 or 7.4%. Finally, the top 0.01% household making $9,936,000 would pay $2,980,757, saving $910,000 or 9.1%.

Thus, like Trump’s plan, the tax cut almost across the board results in less revenue. However, because of the basic income, we can now justify cutting a lot of spending on social welfare programs. I estimated we could reasonably save about $630 billion by cutting Medicaid and other social welfare programs, while still not making poor people worse off because of the basic income. The resulting estimated deficit comes in at $1.085 trillion, which is still too large—but less than what Trump is proposing.

If I raise the flat rate to 40%—just as easy to calculate—I can bring that deficit down, even if I raise the basic income to $15,000 to compensate. The poverty household now receives $10,073, and the other representative households pay $5,974; $45,776; $297,615; $799,666; and $3,959,343 respectively. This means that the poor are again much better off, the middle class are about the same, and the rich are now substantially worse off. But what’s our deficit now? $180 billion—that’s about 1% of GDP, the sort of thing you can maintain indefinitely with a strong currency.

Can we do better than this? I think we can, with my logtax.

I confess that the logtax is not quite as easy to calculate as the flat tax. It does require taking exponents, and you can’t do it in your head. But it’s actually still easier than the current system, because there are no brackets to keep track of, no discontinuous shifts in the marginal rate. It is continuously progressive for all incomes, and the same formula can be used for all incomes from zero to infinity.

The simplest plan just replaces the income tax with a logtax of 20%. The poor household now receives $1,254, just from the automatic calculation of the tax—no basic income was added. The middle-class household pays $9,041, slightly more than what they are currently paying. Above that, people start paying more for sure: $50,655; $406,076; $1,228,795; and $7,065,274 respectively.

This system is obviously more progressive, but does it raise sufficient revenue? Why, as a matter of fact it removes the deficit entirely. The model estimates that the budget would now be at surplus of $110 billion. This is probably too optimistic; under dynamic scoring the distortions are probably going to cut the revenue a little. But it would almost certainly reduce the deficit, and very likely eliminate it altogether—without any changes in spending.

The next logtax plan adds a basic income of $12,000. To cover this, I raised the metarate to 25%. Now the poor household is receiving $11,413, the middle-class household is paying a mere $1,115, and the other households are paying $50,144; $458,140; $1,384,475; and $7,819,932 respectively. That top 0.01% household isn’t going to be happy, as they are now paying 78% of their income where in our current system they would pay only 39%. But their after-tax income is still over $2 million.

How does the budget look now? As with the flat tax plan, we can save about $630 billion by cutting redundant social welfare programs. So we are once again looking at a surplus, this time of about $63 billion. Again, the dynamic scoring might show some deficit, but definitely not a large one.

Finally, what if I raise the basic income to $15,000 and raise the metarate to 35%? The poor household now receives $14,186, while the median household pays $2,383. The richer households of course foot the bill, paying $64,180; $551,031; $1,618,703; and $8,790,124 respectively. Oh no, the top 0.01% household will have to make do with only $1.2 million; how will they survive!?

This raises enough revenue that it allows me to do some even more exciting things. With a $15,000 basic income, I can eliminate social welfare programs for sure. But then I can also cut military spending, say in half—still leaving us the largest military in the world. I can move funds around to give Medicare to every single American, an additional cost of about twice what we currently pay for Medicare. Then Medicaid doesn’t just get cut; it can be eliminated entirely, folded into Medicare. Assuming that the net effect on total spending is zero, the resulting deficit is estimated at only $168 billion, well within the range of what can be sustained indefinitely.

And really, that’s only the start. Once you consider all the savings on healthcare spending—an average of $4000 per person per year, if switching to single-payer brings us down to the average of other highly-developed countries. This is more than what the majority of the population would be paying in taxes under this plan—meaning that once you include the healthcare benefits, the majority of Americans would net receive money from the government. Compared to our current system, everyone making under about $80,000 would be better off. That is what we could be doing right now—free healthcare for everyone, a balanced budget (or close enough), and the majority of Americans receiving more from the government than they pay in taxes.

These results are summarized in the table below. (I also added several more rows of representative households—though still not all the brackets I used!) I’ve color-coded who would be paying less in tax in green and who would be more in tax in red under each plan, compared to our current system. This color-coding is overly generous to Trump’s plan and the 30% flat tax plan, because it doesn’t account for the increased government deficit (though I did color-code those as well, again relative to the current system). And yet, over 50% of households make less than $51,986, putting the poorest half of Americans in the green zone for every plan except Trump’s. For the last plan, I also color-coded those between $52,000 and $82,000 who would pay additional taxes, but less than they save on healthcare, thus net saving money in blue. Including those folks, we’re benefiting over 69% of Americans.

| Household

pre-tax income |

Current tax system |

Trump’s tax plan |

Flat 30% tax with $12k basic income |

Flat 40% tax with $15k basic income |

Logtax 20% |

Logtax 25% with $12k basic income |

Logtax 35% with $15k basic income, single-payer healthcare |

| $1,080 |

$108 |

$130 |

-$11,676 |

-$14,568 |

-$856 |

-$12,121 |

-$15,173 |

| $12,317 |

$1,384 |

$1,478 |

-$8,305 |

-$10,073 |

-$1,254 |

-$11,413 |

-$14,186 |

| $22,162 |

$2,861 |

$2,659 |

-$5,351 |

-$6,135 |

$450 |

-$9,224 |

-$11,213 |

| $32,058 |

$4,345 |

$3,847 |

-$2,383 |

-$2,177 |

$2,887 |

-$6,256 |

-$7,258 |

| $51,986 |

$8,768 |

$6,238 |

$3,596 |

$5,794 |

$9,041 |

$1,115 |

$2,383 |

| $77,023 |

$15,027 |

$9,506 |

$11,107 |

$15,809 |

$18,206 |

$11,995 |

$16,350 |

| $81,966 |

$16,263 |

$10,742 |

$12,590 |

$17,786 |

$20,148 |

$14,292 |

$17,786 |

| $97,161 |

$20,242 |

$14,540 |

$17,148 |

$23,864 |

$26,334 |

$21,594 |

$28,516 |

| $101,921 |

$21,575 |

$15,730 |

$18,576 |

$27,875 |

$30,571 |

$23,947 |

$31,482 |

| $151,940 |

$35,580 |

$28,235 |

$33,582 |

$45,776 |

$50,655 |

$50,144 |

$64,180 |

| $781,538 |

$265,625 |

$230,158 |

$222,461 |

$297,615 |

$406,076 |

$458,140 |

$551,031 |

| $2,036,666 |

$762,656 |

$644,350 |

$599,000 |

$799,666 |

$1,228,795 |

$1,384,475 |

$1,618,703 |

| $9,935,858 |

$3,890,736 |

$3,251,083 |

$2,968,757 |

$3,959,343 |

$7,065,274 |

$7,819,932 |

$8,790,124 |

| Change in federal spending |

$0 |

$0 |

-$630 billion |

-$630 billion |

$0 |

-$630 billion |

$0 |

| Estimated federal surplus |

-$682 billion |

-$1,155 billion |

-$822 billion |

-$180 billion |

$110 billion |

$63 billion |

-$168 billion |