Jan 25 JDN 2461066

Scott Alexander has a techno-utopian vision:

Between the vast ocean of total annihilation and the vast continent of infinite post-scarcity, there is, I admit, a tiny shoreline of possibilities that end in oligarch capture. Even if you end up there, you’ll be fine. Dario Amodei has taken the Giving What We Can Pledge (#43 here) to give 10% of his wealth to the less fortunate; your worst-case scenario is owning a terraformed moon in one of his galaxies. Now you can stop worrying about the permanent underclass and focus on more important things.

I agree that total annihilation is a very serious risk, though fortunately I believe it is not the most likely outcome. But it seems pretty weird to me to posit that the most likely outcome is “infinite post-scarcity” when oligarch capture is what we already have.

(Regarding Alexander’s specific example: Dario Amidei has $3.7 billion. If he were to give away 10% of that, it would be $370 million, which would be good, but hardly usher in a radical utopia. The assumption seems to be that he would be one of the prevailing trillionaire oligarchs, and I don’t see how we can know that would be the case. Even if AI succeeds in general, that doesn’t mean that every company that makes AI succeeds. (Video games succeeded, but who buys Atari anymore?) Also, it seems especially wide-eyed to imagine that one man would ever own entire galaxies. We probably won’t even ever be able to reach other galaxies!)

People with this sort of utopian vision seem to imagine that all we need to do is make more stuff, and then magically it will all be distributed in such a way that everyone gets to have enough.

If Alexander were writing 200 years ago, I could even understand why he’d think that; there genuinely wasn’t enough stuff to go around, and it would have made sense to think that all we needed to do was solve that problem, and then the other problems would be easy.

But we no longer live in that world.

There is enough stuff to go around—at the very least this is true of all highly-developed countries, and it’s honestly pretty much true of the world as a whole. The problem is very much that it isn’t going around.

Elon Musk’s net wealth is now estimated at over $780 billion. Seven hundred and eighty billion dollars. He could give $90 to every person in the world (all 8.3 billion of us). He could buy a home (median price $400,000—way higher than it was just a few years ago) for every homeless person in America (about 750,000 people) and still have half his wealth left over. He could give $900 to every single person of the 831 million people who live below the world extreme poverty threshold—thus eliminating extreme poverty in the world for a year. (And quite possibly longer, as all those people are likely to be more productive now that they are well-fed.) He has chosen to do none of these things, because he wants to see number go up.

That’s just one man. If you add up all the wealth of all the world’s billionaires—just billionaires, so we’re not even counting people with $50 million or $100 million or $500 million—it totals over $16 trillion. This is enough to not simply end extreme poverty for a year, but to establish a fund that would end it forever.

And don’t tell me that they can’t really do this because it’s all tied up in stocks and not liquid. UNICEF happily accepts donations in stock. Giving UNICEF $10 trillion in stocks absolutely would permanently end extreme poverty worldwide. And they could donate those stocks today. They are choosing not to.

I still think that AI is a bubble that’s going to burst and trigger a financial crisis. But there is some chance that AI actually does become a revolutionary new technology that radically increases productivity. (In fact, I think this will happen, eventually. I just think we’re a paradigm or two away from that, and LLMs are largely a dead end.)

But even if that happens, unless we have had radical changes in our economy and society, it will not usher in a new utopian era of plenty for all.

How do I know this? Because if that were what the powers that be wanted to happen, they would have already started doing it. The super-rich are now so absurdly wealthy that they could easily effect great reductions in poverty at home and abroad while costing themselves basically nothing in terms of real standard of living, but they are choosing not to do that. And our governments could be taxing them more and using those funds to help people, and they are by and large choosing not to do that either.

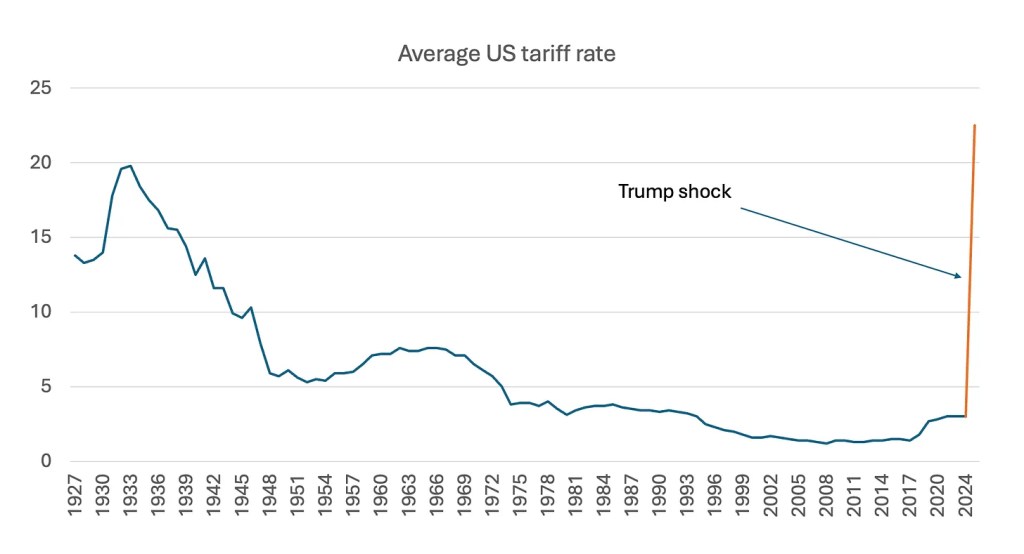

The notion seems to be similar to “trickle-down economics”: Once the rich get rich enough, they’ll finally realize that money can’t buy happiness and start giving away their vast wealth to help people. But if that didn’t happen at $100 million, or $1 billion, or $10 billion, or $100 billion, I see no reason to think that it will happen at $1 trillion or $10 trillion or even $100 trillion.