Aug 17 JDN 2460905

Donald Trump has federalized the police in Washington D.C. and deployed the National Guard. He claims he is doing this in response to a public safety emergency and crime that is “out of control”.

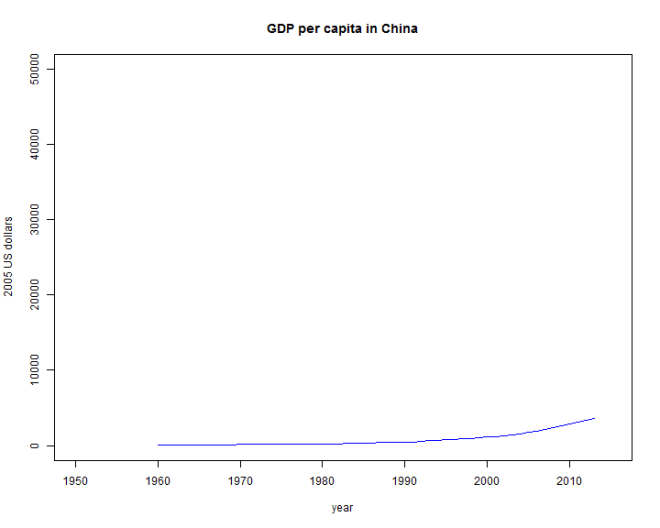

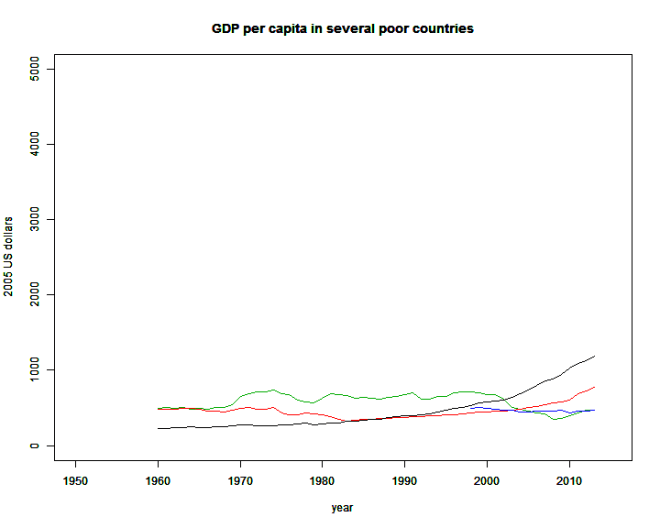

Crime rates in Washington, D.C. are declining and overall at their lowest level in 30 years. Its violent crime rate has not been this low since the 1960s.

By any objective standard, there is no emergency here. Crime in D.C. is not by any means out of control.

Indeed, across the United States, homicide rates are as low as they have been in 60 years.

But we do not live in a world where politics is based on objective truth.

We live in a world where the public perception of reality itself is shaped by the political narrative.

One of the first things that authoritarians do to control these narratives is try to make their followers distrust objective sources. I watch in disgust as not simply the Babylon Bee (which is a right-wing satire site that tries really hard to be funny but never quite manages it) but even the Atlantic (a mainstream news outlet generally considered credible) feeds—in multiple articles—into this dangerous lie that crime is increasing and the official statistics are somehow misleading us about that.

Of course the Atlantic‘s take is much more nuanced; but quite frankly, now is not the time for nuance. A fascist is trying to take over our government, and he needs to be resisted at every turn by every means possible. You need to be calling him out on every single lie he makes—yes, every single one, I know there are a lot of them, and that’s kind of the point—rather than trying to find alternative framings on which maybe part of what he said could somehow be construed as reasonable from a certain point of view. Every time you make Trump sound more reasonable than he is—and mainstream news outlets have done this literally hundreds of times—you are pushing America closer to fascism.

I really don’t know what to do here.

It is impossible to resolve conflicts when they are not based on shared reality.

No policy can solve a crime wave that doesn’t exist. No trade agreement can stop unfair trading practices that aren’t happening. Nothing can stop vaccines from causing autism that they already don’t cause. There is no way to fix problems when those problems are completely imaginary.

I used to think that political conflict was about different values which had to be balanced against one another: Liberty versus security, efficiency versus equality, justice versus mercy. I thought that we all agreed on the basic facts and even most of the values, and were just disagreeing about how to weigh certain values over others.

Maybe I was simply naive; maybe it’s never been like that. But it certainly isn’t right now. We aren’t disagreeing about what should be done; we are disagreeing about what is happening in front of our eyes. We don’t simply have different priorities or even different values; it’s like we are living in different worlds.

I have read, e.g. by Jonathan Haidt, that conservatives largely understand what liberals want, but liberals don’t really understand what conservatives want. (I would like to take one of the tests they use in these experiments, see how I actually do; but I’ve never been able to find one.)

Haidt’s particular argument seems to be that liberals don’t “understand” the “moral dimensions” of loyalty, authority, and sanctity, because we only “understand” harm and fairness as the basis of morality. But just because someone says something is morally relevant, that doesn’t mean it is morally relevant! And indeed, based on more or less the entirety of ethical philosophy, I can say that harm and fairness are morality, and the others simply aren’t. They are distortions of morality, they are inherently evil, and we are right to oppose them at every turn. Loyalty, authority, and sanctity are what fed Nazi Germany and the Spanish Inquisition.

This claim that liberals don’t understand conservatives has always seemed very odd to me: I feel like I have a pretty clear idea what conservatives want, it’s just that what they want is terrible: Kick out the immigrants, take money from the poor and give it to the rich, and put rich straight Christian White men back in charge of everything. (I mean, really, if that’s not what they want, why do they keep voting for people who do it? Revealed preferences, people!)

Or, more sympathetically: They want to go back to a nostalgia-tinted vision of the 1950s and 1960s in which it felt like things were going well for our country—because they were blissfully ignorant of all the violence and injustice in the world. No, thank you, Black people and queer people do not want to go back to how we were treated in the 1950s—when segregation was legal and Alan Turing was chemically castrated. (And they also don’t seem to grasp that among the things that did make some things go relatively well in that period were unions, antitrust law and progressive taxes, which conservatives now fight against at every turn.)

But I think maybe part of what’s actually happening here is that a lot of conservatives actually “want” things that literally don’t make sense, because they rest upon assumptions about the world that simply aren’t true.

They want to end “out of control” crime that is the lowest it’s been in decades.

They want to stop schools from teaching things that they already aren’t teaching.

They want the immigrants to stop bringing drugs and crime that they aren’t bringing.

They want LGBT people to stop converting their children, which we already don’t and couldn’t. (And then they want to do their own conversions in the other direction—which also don’t work, but cause tremendous harm.)

They want liberal professors to stop indoctrinating their students in ways we already aren’t and can’t. (If we could indoctrinate our students, don’t you think we’d at least make them read the syllabus?)

They want to cut government spending by eliminating “waste” and “fraud” that are trivial amounts, without cutting the things that are actually expensive, like Social Security, Medicare, and the military. They think we can balance the budget without cutting these things or raising taxes—which is just literally mathematically impossible.

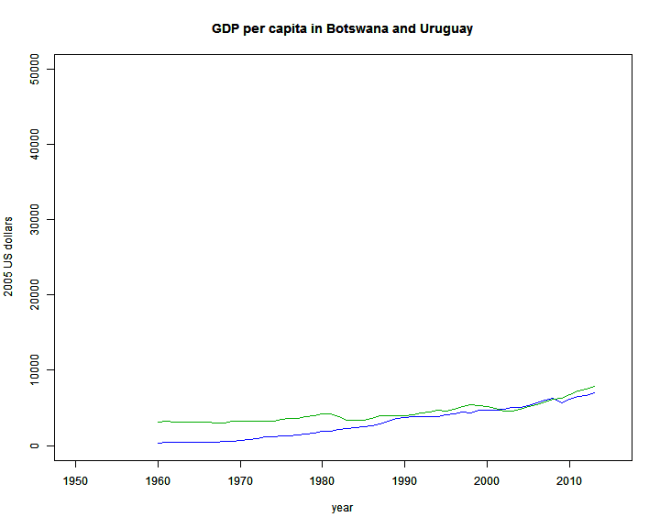

They want to close off trade to bring back jobs that were sent offshore—but those jobs weren’t sent offshore, they were replaced by robots. (US manufacturing output is near its highest ever, even though manufacturing employment is half what it once was.)

And meanwhile, there’s a bunch of real problems that aren’t getting addressed: Soaring inequality, a dysfunctional healthcare system, climate change, the economic upheaval of AI—and they either don’t care about those, aren’t paying attention to them, or don’t even believe they exist.

It feels a bit like this:

You walk into a room and someone points a gun at you, shouting “Drop the weapon!” but you’re not carrying a weapon. And you show your hands, and try to explain that you don’t have a weapon, but they just keep shouting “Drop the weapon!” over and over again. Someone else has already convinced them that you have a weapon, and they expect you to drop that weapon, and nothing you say can change their mind about this.

What exactly should you do in that situation?

How do you avoid getting shot?

Do you drop something else and say it’s the weapon (make some kind of minor concession that looks vaguely like what they asked for)? Do you try to convince them that you have a right to the weapon (accept their false premise but try to negotiate around it)? Do you just run away (leave the country?)? Do you double down and try even harder to convince them that you really, truly, have no weapon?

I’m not saying that everyone on the left has a completely accurate picture of reality; there are clearly a lot of misconceptions on this side of the aisle as well. But at least among the mainstream center left, there seems to be a respect for objective statistics and a generally accurate perception of how the world works—the “reality-based community”. Sometimes liberals make mistakes, have bad ideas, or even tell lies; but I don’t hear a lot of liberals trying to fix problems that don’t exist or asking for the government budget to be changed in ways that violate basic arithmetic.

I really don’t know what do here, though.

How do you change people’s minds when they won’t even agree on the basic facts?