JDN 2457064

I’m sure you’ve already heard this plenty of times before, but just in case here are a few particularly notable examples: “Millennials are entitled.” “Millennials are narcissistic.” “Millennials expect instant gratification.”

Fortunately there are some more nuanced takes as well: One survey shows that we are perceived as “entitled” and “self-centered” but also “hardworking” and “tolerant”. This article convincingly argues that Baby Boomers show at least as much ‘entitlement’ as we do. Another article points out that young people have been called these sorts of names for decades—though actually the proper figure is centuries.

Though some of the ‘defenses’ leave a lot to be desired: “OK, admittedly, people do live at home. But that’s only because we really like our parents. And why shouldn’t we?” Uh, no, that’s not it. Nor is it that we’re holding off on getting married. The reason we live with our parents is that we have no money and can’t pay for our own housing. And why aren’t we getting married? Because we can’t afford to pay for a wedding, much less buy a home and start raising kids. (Since the time I drafted this for Patreon and it went live, yet another article hand-wringing over why we’re not getting married was published—in Scientific American, of all places.)

Are we not buying cars because we don’t like cars? No, we’re not buying cars because we can’t afford to pay for them.

The defining attributes of the Millennial generation are that we are young (by definition) and broke (with very few exceptions). We’re not uniquely narcissistic or even tolerant; younger generations always have these qualities.

But there may be some kernel of truth here, which is that we were promised a lot more than we got.

Educational attainment in the United States is the highest it has ever been. Take a look at this graph from the US Department of Education:

Percentage of 25- to 29-year-olds who completed a bachelor’s or higher degree, by race/ethnicity: Selected years, 1990–2014

More young people of every demographic except American Indians now have college degrees (and those figures fluctuate a lot because of small samples—whether my high school had an achievement gap for American Indians depended upon how I self-identified on the form, because there were only two others and I was tied for the highest GPA).

Even the IQ of Millennials is higher than that of our parents’ generation, which is higher than their parents’ generation; (measured) intelligence rises over time in what is called the Flynn Effect. IQ tests have to be adjusted to be harder by about 3 points every 10 years because otherwise the average score would stop being 100.

As your level of education increases, your income tends to go up and your unemployment tends to go down. In 2014, while people with doctorates or professional degrees had about 2% unemployment and made a median income of $1590 per week, people without even high school diplomas had about 9% unemployment and made a median income of only $490 per week. The Bureau of Labor Statistics has a nice little bar chart of these differences:

Now the difference is not quite as stark. With the most recent data, the unemployment rate is 6.7% for people without a high school diploma and 2.5% for people with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

But that’s for the population as a whole. What about the population of people 18 to 35, those of us commonly known as Millennials?

Well, first of all, our unemployment rate overall is much higher. With the most recent data, unemployment among people ages 20-24 is a whopping 9.4%. For ages 25 to 34 it gets better, 5.3%; but it’s still much worse than unemployment at ages 35-44 (4.0%), 45-54 (3.6%), or 55+ (3.2%). Overall, unemployment among Millennials is about 6.7% while unemployment among Baby Boomers is about 3.2%, half as much. (Gen X is in between, but a lot closer to the Boomers at around 3.8%.)

It was hard to find data specifically breaking it down by both age and education at the same time, but the hunt was worth it.

Among people age 20-24 not in school:

Without a high school diploma, 328,000 are unemployed, out of 1,501,000 in the labor force. That’s an unemployment rate of 21.9%. Not a typo, that’s 21.9%.

With only a high school diploma, 752,000 are unemployed, out of 5,498,000 in the labor force. That’s an unemployment rate of 13.7%.

With some college but no bachelor’s degree, 281,000 are unemployed, out of 3,620,000 in the labor force. That’s an unemployment rate of 7.7%.

With a bachelor’s degree, 90,000 are unemployed, out of 2,313,000 in the labor force. That’s an unemployment rate of 3.9%.

What this means is that someone 24 or under needs to have a bachelor’s degree in order to have the same overall unemployment rate that people from Gen X have in general, and even with a bachelor’s degree, people under 24 still have a higher unemployment rate than what Baby Boomers simply have by default. If someone under 24 doesn’t even have a high school diploma, forget it; their unemployment rate is comparable to the population unemployment rate at the trough of the Great Depression.

In other words, we need to have college degrees just to match the general population older than us, of whom only 20% have a college degree; and there is absolutely nothing a Millennial can do in terms of education to ever have the tiny unemployment rate (about 1.5%) of Baby Boomers with professional degrees. (Be born White, be in perfect health, have a professional degree, have rich parents, and live in a city with very high employment, and you just might be able to pull it off.)

So, why do Millennials feel like a college degree should “entitle” us to a job?

Because it does for everyone else.

Why do we feel “entitled” to a higher standard of living than the one we have?

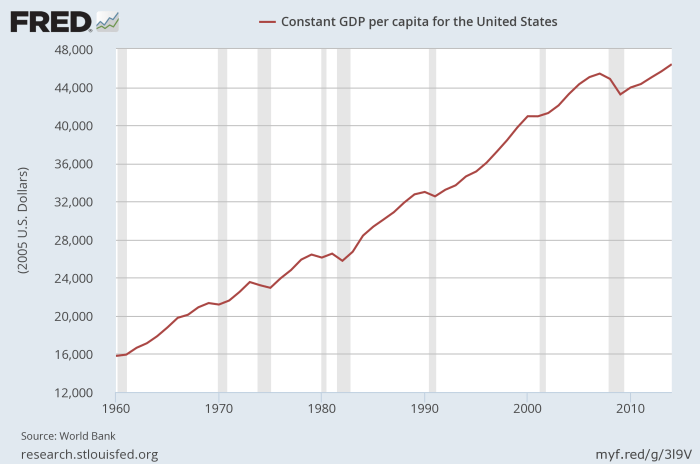

Take a look at this graph of GDP per capita in the US:

You may notice a rather sudden dip in 2009, around the time most Millennials graduated from college and entered the labor force. On the next graph, I’ve added a curve approximating what it would look like if the previous trend had continued:

(There’s a lot on this graph for wonks like me. You can see how the unit-root hypothesis seemed to fail in the previous four recessions, where economic output rose back up to potential; but it clearly held in this recession, and there was a permanent loss of output. It also failed in the recession before that. So what’s the deal? Why do we recover from some recessions and take a permanent blow from others?)

If the Great Recession hadn’t happened, instead of per-capita GDP being about $46,000 in 2005 dollars, it would instead be closer to $51,000 in 2005 dollars. In today’s money, that means our current $56,000 would be instead closer to $62,000. If we had simply stayed on the growth trajectory we were promised, we’d be almost 10 log points richer (11% for the uninitiated).

So, why do Millennials feel “entitled” to things we don’t have? In a word, macroeconomics.

People anchored their expectations of what the world would be like on forecasts. The forecasts said that the skies were clear and economic growth would continue apace; so naturally we assumed that this was true. When the floor fell out from under our economy, only a few brilliant and/or lucky economists saw it coming; even people who were paying quite close attention were blindsided. We were raised in a world where economic growth promised rising standard of living and steady employment for the rest of our lives. And then the storm hit, and we were thrown into a world of poverty and unemployment—and especially poverty and unemployment for us.

We are angry about how we had been promised more than we were given, angry about how the distribution of what wealth we do have gets ever more unequal. We are angry that our parents’ generation promised what they could not deliver, and angry that it was their own blind worship of the corrupt banking system that allowed the crash to happen.

And because we are angry and demand a fairer share, they have the audacity to call us “narcissistic”.