Dec 1 JDN 2460646

Super-human beings aren’t that strange a thing to posit, but they are the sort of thing we’d expect to see clear evidence of if they existed. Without them, prayer is a muddled concept that is difficult to distinguish from simply “things that don’t work”. That leaves the afterlife. Could there be an existence for human consciousness after death?

No. There isn’t. Once you’re dead, you’re dead. It’s really that unequivocal. It is customary in most discussions of this matter to hedge and fret and be “agnostic” about what might lie beyond the grave—but in fact the evidence is absolutely overwhelming.

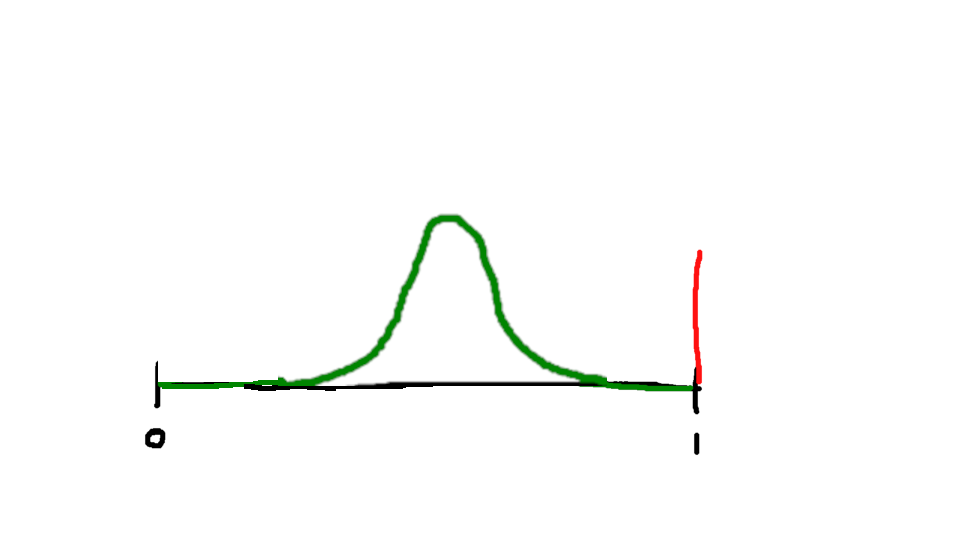

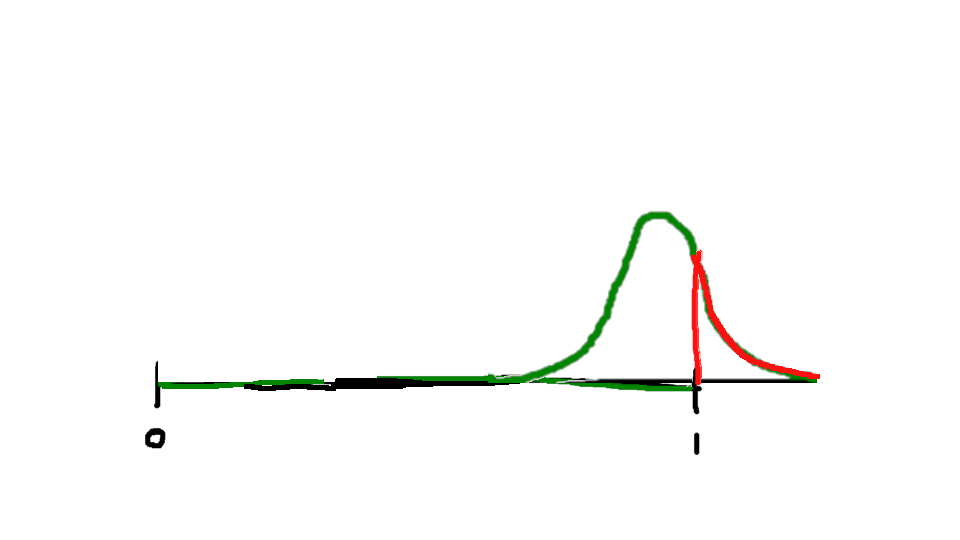

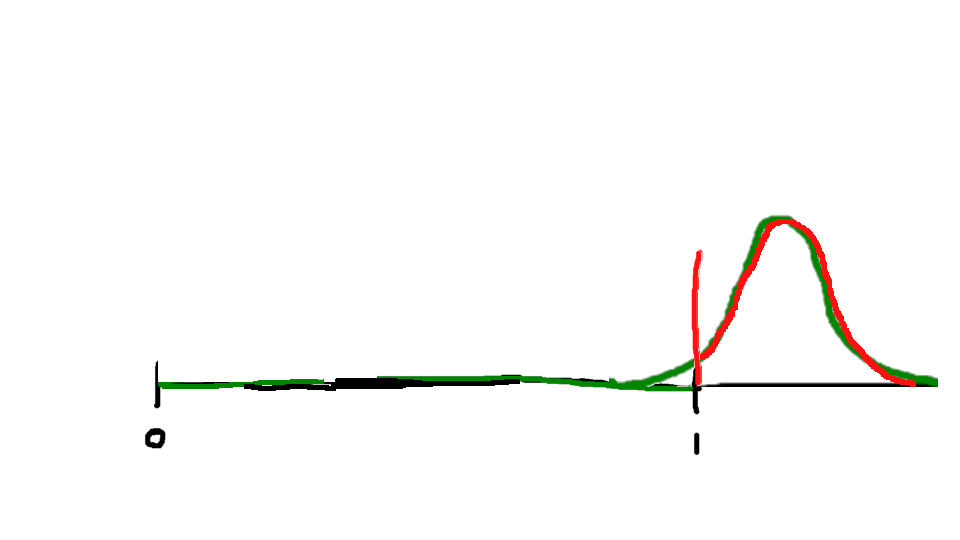

Everything we know about neuroscience—literally everything—would have to be abandoned in order for an afterlife to make sense. The core of neuroscience, the foundation from which the entire field is built, is what I call the Basic Fact of Cognitive Science: you are your brain. It is your brain that feels, your brain that thinks, your brain that dreams, your brain that remembers. We do not yet understand most of these processes in detail—though some we actually do, such as the processing of visual images. But it doesn’t take an expert mechanic to know that removing the engine makes the car stop running. It doesn’t take a brilliant electrical engineer to know that smashing the CPU makes the computer stop working. Saying that your mind continues to work without your brain is like saying that you can continue to digest without having a stomach or intestines.

This fundamental truth underlies everything we know about the science of consciousness. It can even be directly verified in a piecemeal form: There are specific areas of your brain that, when damaged, will cause you to become blind, or unable to understand language, or unable to speak grammatically (those are two distinct areas), or destroy your ability to form new memories or recall old ones, or even eliminate your ability to recognize faces. Most terrifying of all—yet by no means surprising to anyone who really appreciates the Basic Fact—is the fact that damage to certain parts of your brain will even change your personality, often making you impulsive, paranoid or cruel, literally making you a worse person. More surprising and baffling is the fact that cutting your brain down the middle into left and right halves can split you into two people, each of whom operates half of your body (the opposite half, oddly enough), who mostly agree on things and work together but occasionally don’t. All of these are people we can actually interact with in laboratories, and (except for language deficits of course) talk to them about their experiences. It’s true that we can’t ask people what it’s like when their whole brain is dead, but of course not; there’s nobody left to ask.

This means that if you take away all the functions that experiments have shown require certain brain parts to function, whatever “soul” is left that survives brain death cannot do any of the following: See, hear, speak, understand, remember, recognize faces, or make moral decisions. In what sense is that worth calling a “soul”? In what sense is that you? Those are just the ones we know for sure; as our repertoire expands, more and more cognitive functions will be mapped to specific brain regions. And of course there’s no evidence that anything survives whatsoever.

Nor are near-death experiences any kind of evidence of an afterlife. Yes, some people who were close to dying or briefly technically dead (“He’s only mostly dead!”) have had very strange experiences during that time. Of course they did! Of course you’d have weird experiences as your brain is shutting down or struggling to keep itself online. Think about a computer that has had a magnet run over its hard drive; all sorts of weird glitches and errors are going to occur. (In fact, powerful magnets can have an effect on humans not all that dissimilar from what weaker magnets can do to computers! Certain sections of the brain can be disrupted or triggered in this way; it’s called transcranial magnetic stimulation and it’s actually a promising therapy for some neurological and psychological disorders.) People also have a tendency to over-interpret these experiences as supporting their particular religion, when in fact it’s usually something no more complicated than “a bright light” or “a long tunnel” (another popular item is “positive feelings”). If you stop and think about all the different ways you might come to see “a bright light” and have “positive feelings”, it should be pretty obvious that this isn’t evidence of St. Paul and the Pearly Gates.

The evidence against an afterlife is totally overwhelming. The fact that when we die, we are gone, is among the most certain facts in science. So why do people cling to this belief? Probably because it’s comforting—or rather because the truth that death is permanent and irrevocable is terrifying. You’re damn right it is; it’s basically the source of all other terror, in fact. But guess what? “Terrifying” does not mean “false”. The idea of an afterlife may be comforting, but it’s still obviously not true.

While I was in the process of writing this book, my father died of a ruptured intracranial aneurysm. The event was sudden and unexpected, and by the time I was able to fly from California to Michigan to see him, he had already lost consciousness—for what would turn out to be forever. This event caused me enormous grief, grief from which I may never fully recover. Nothing would make me happier than knowing that he was not truly gone, that he lives on somewhere watching over me. But alas, I know it is not true. He is gone. Forever.

However, I do have a couple of things to say that might offer some degree of consolation:

First, because human minds are software, pieces of our loved ones do go on—in us. Our memories of those we have lost are tiny shards of their souls. When we tell stories about them to others, we make copies of those shards; or to use a more modern metaphor, we back up their data in the cloud. Were we to somehow reassemble all these shards together, we could not rebuild the whole person—there are always missing pieces. But it is also not true that nothing remains. What we have left is how they touched our lives. And when we die, we will remain in how we touch the lives of others. And so on, and so on, as the ramifications of our deeds in life and the generations after us ripple out through the universe at the speed of light, until the end of time.

Moreover, if there’s no afterlife there can be no Hell, and Hell is literally the worst thing imaginable. To subject even a single person—even the most horrible person who ever lived, Hitler, Stalin, Mao, whomever—to the experience of maximum possible suffering forever is an atrocity of incomparable magnitude. Hitler may have deserved a million years of suffering for what he did—but I’m not so sure about maximum suffering, and forever is an awful lot longer than a million years. Indeed, forever is so much longer than a million years that if your sentence is forever, then after serving a million years you still have as much left to go as when you began. But the Bible doesn’t even just say that the most horrible mass murderers will go to Hell; no, it says everyone will go to Hell by default, and deserve it, and can only be forgiven if we believe. No amount of good works will save us from this fate, only God’s grace.

If you believe this—or even suspect it—religion has caused you deep psychological damage. This is the theology of an abusive father—“You must do exactly as I say, or you are worthless and undeserving of love and I will hurt you and it will be all your fault.” No human being, no matter what they have done or failed to do, could ever possibly deserve a punishment as terrible as maximum possible suffering forever. Even if you’re a serial rapist and murderer—and odds are, you’re not—you still don’t deserve to suffer forever. You have lived upon this planet for only a finite time; you can therefore only have committed finitely many crimes and you can only deserve at most finite suffering. In fact, the vast majority of the world’s population is comprised of good, decent people who deserve joy, not suffering.

Indeed, many ethicists would say that nobody deserves suffering, it is simply a necessary evil that we use as a deterrent from greater harms. I’m actually not sure I buy this—if you say that punishment is all about deterrence and not about desert, then you end up with the result that anything which deters someone could count as a fair punishment, even if it’s inflicted upon someone else who did nothing wrong. But no ethicist worthy of the name believes that anybody deserves eternal punishment—yet this is what Jesus says we all deserve in the Bible. And Muhammad says similar things in the Qur’an, about lakes of eternal burning (4:56) and eternal boiling water to drink (47:15) and so on. It’s entirely understandable that such things would motivate you—indeed, they should motivate you completely to do just about anything—if you believed they were true. What I don’t get is why anybody would believe they are true. And I certainly don’t get why anyone would be willing to traumatize their children with these horrific lies.

Then there is Pascal’s Wager: An infinite punishment can motivate you if it has any finite probability, right? Theoretically, yes… but here’s the problem with that line of reasoning: Anybody can just threaten you with infinite punishment to make you do anything. Clearly something is wrong with your decision theory if any psychopath can just make you do whatever he wants because you’re afraid of what might happen just in case what he says might possibly be true. Beware of plausible-seeming theories that lead to such absurd conclusions; it may not be obvious what’s wrong with the argument, but it should be obvious that something is.