Sep 17 JDN 2460205

As someone who experiences a great deal of anxiety, I have often struggled to understand what it could possibly be useful for. We have this whole complex system of evolved emotions, and yet more often than not it seems to harm us rather than help us. What’s going on here? Why do we even have anxiety? What even is anxiety, really? And what is it for?

There’s actually an extensive body of research on this, though very few firm conclusions. (One of the best accounts I’ve read, sadly, is paywalled.)

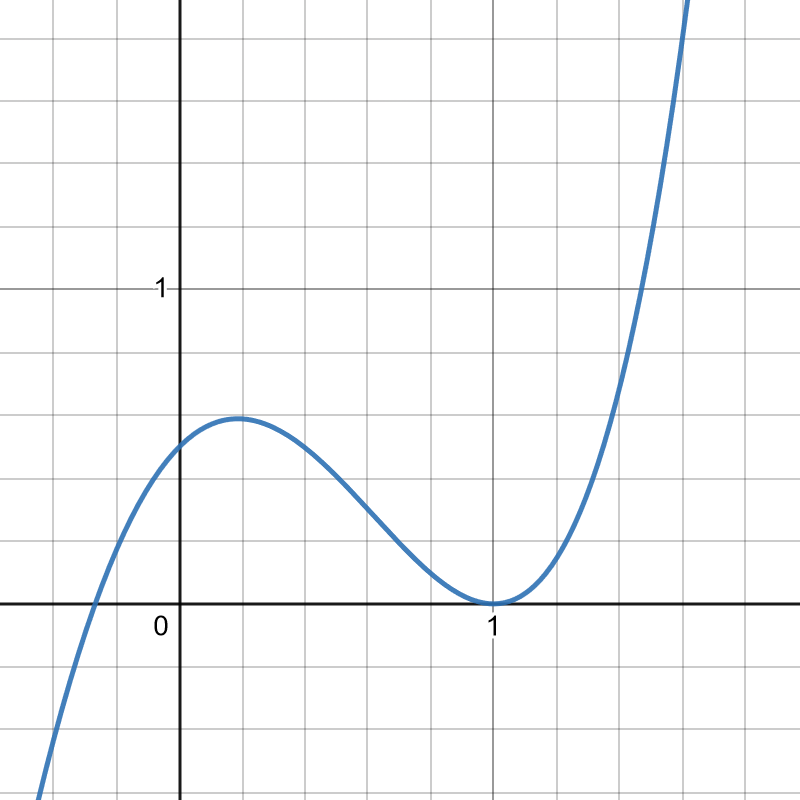

For one thing, there seem to be a lot of positive feedback loops involved in anxiety: Panic attacks make you more anxious, triggering more panic attacks; being anxious disrupts your sleep, which makes you more anxious. Positive feedback loops can very easily spiral out of control, resulting in responses that are wildly disproportionate to the stimulus that triggered them.

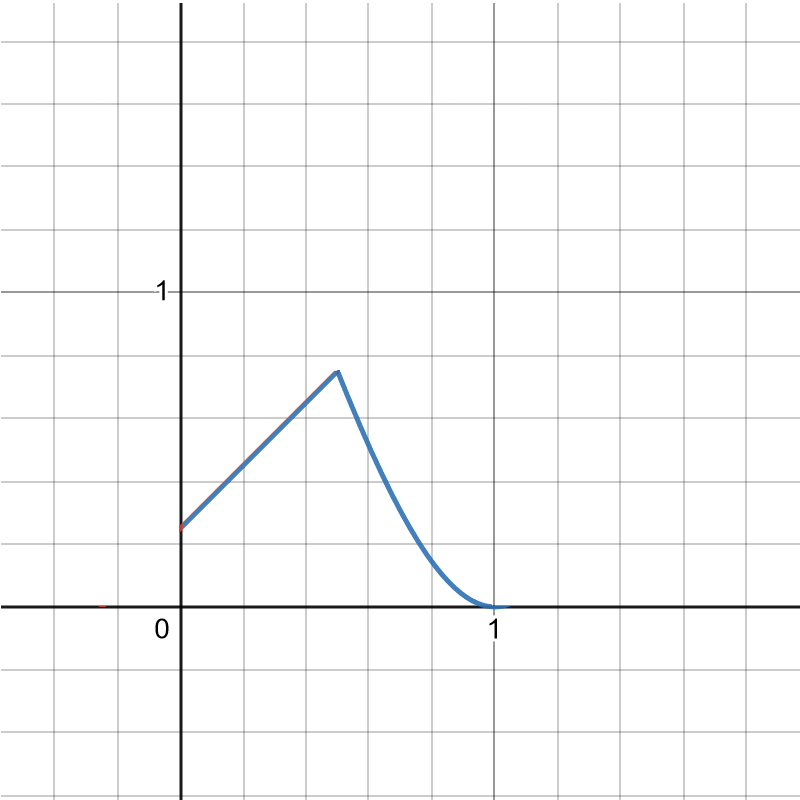

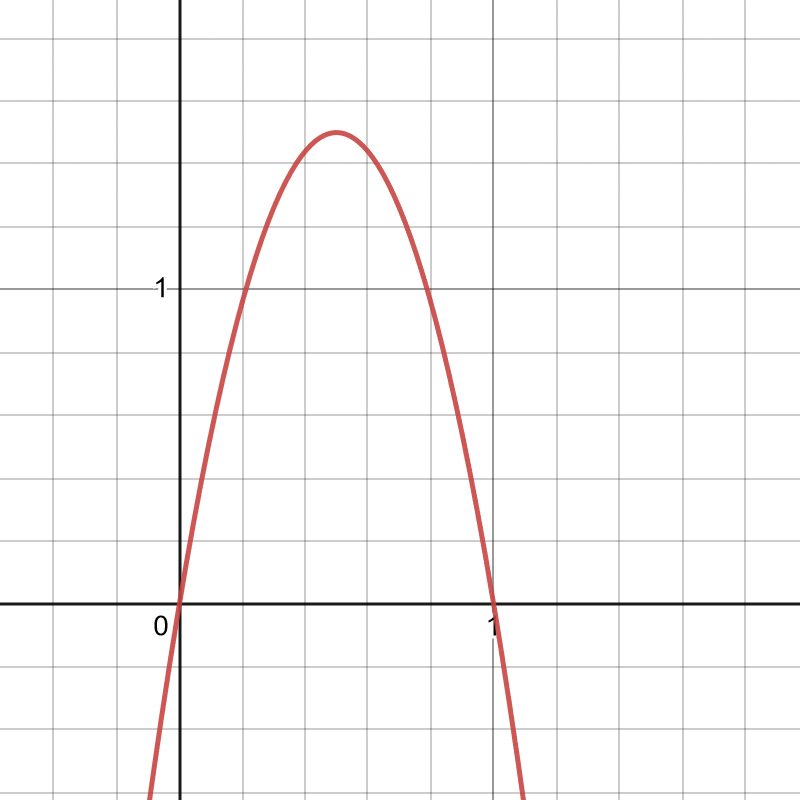

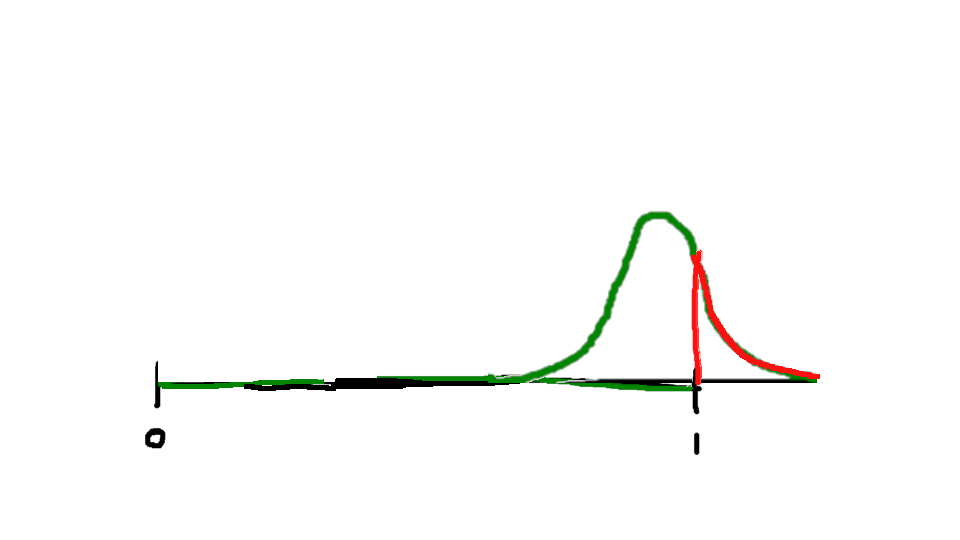

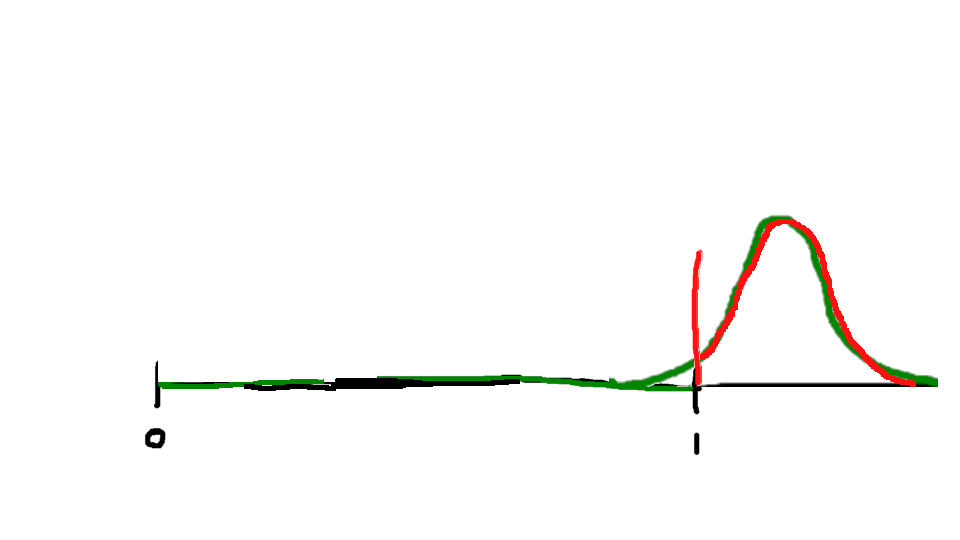

A certain amount of stress response is useful, even when the stakes are not life-or-death. But beyond a certain point, more stress becomes harmful rather than helpful. This is the Yerkes-Dodson effect, for which I developed my stochastic overload model (which I still don’t know if I’ll ever publish, ironically enough, because of my own excessive anxiety). Realizing that anxiety can have benefits can also take some of the bite out of having chronic anxiety, and, ironically, reduce that anxiety a little. The trick is finding ways to break those positive feedback loops.

I think one of the most useful insights to come out of this research is the smoke-detector principle, which is a fundamentally economic concept. It sounds quite simple: When dealing with an uncertain danger, sound the alarm if the expected benefit of doing so exceeds the expected cost.

This has profound implications when risk is highly asymmetric—as it usually is. Running away from a shadow or a noise that probably isn’t a lion carries some cost; you wouldn’t want to do it all the time. But it is surely nowhere near as bad as failing to run away when there is an actual lion. Indeed, it might be fair to say that failing to run away from an actual lion counts as one of the worst possible things that could ever happen to you, and could easily be 100 times as bad as running away when there is nothing to fear.

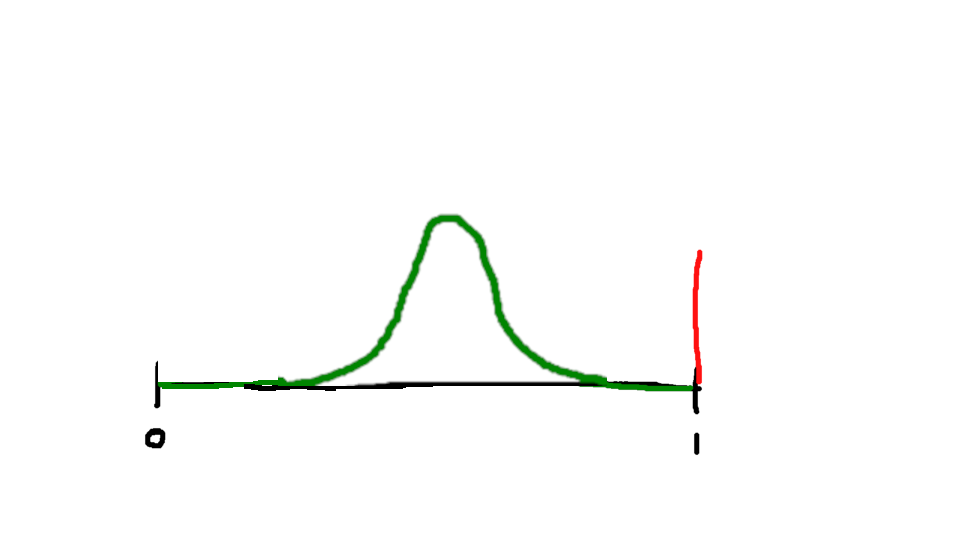

With this in mind, if you have a system for detecting whether or not there is a lion, how sensitive should you make it? Extremely sensitive. You should in fact try to calibrate it so that 99% of the time you experience the fear and want to run away, there is not a lion. Because the 1% of the time when there is one, it’ll all be worth it.

Yet this is far from a complete explanation of anxiety as we experience it. For one thing, there has never been, in my entire life, even a 1% chance that I’m going to be attacked by a lion. Even standing in front of a lion enclosure at the zoo, my chances of being attacked are considerably less than that—for a zoo that allowed 1% of its customers to be attacked would not stay in business very long.

But for another thing, it isn’t really lions I’m afraid of. The things that make me anxious are generally not things that would be expected to do me bodily harm. Sure, I generally try to avoid walking down dark alleys at night, and I look both ways before crossing the street, and those are activities directly designed to protect me from bodily harm. But I actually don’t feel especially anxious about those things! Maybe I would if I actually had to walk through dark alleys a lot, but I don’t, and in the rare occasion I would, I think I’d feel afraid at the time but fine afterward, rather than experiencing persistent, pervasive, overwhelming anxiety. (Whereas, if I’m anxious about reading emails, and I do manage to read emails, I’m usually still anxious afterward.) When it comes to crossing the street, I feel very little fear at all, even though perhaps I should—indeed, it had been remarked that when it comes to the perils of motor vehicles, human beings suffer from a very dangerous lack of fear. We should be much more afraid than we are—and our failure to be afraid kills thousands of people.

No, the things that make me anxious are invariably social: Meetings, interviews, emails, applications, rejection letters. Also parties, networking events, and back when I needed them, dates. They involve interacting with other people—and in particular being evaluated by other people. I never felt particularly anxious about exams, except maybe a little before my PhD qualifying exam and my thesis defenses; but I can understand those who do, because it’s the same thing: People are evaluating you.

This suggests that anxiety, at least of the kind that most of us experience, isn’t really about danger; it’s about status. We aren’t worried that we will be murdered or tortured or even run over by a car. We’re worried that we will lose our friends, or get fired; we are worried that we won’t get a job, won’t get published, or won’t graduate.

And yet it is striking to me that it often feels just as bad as if we were afraid that we were going to die. In fact, in the most severe instances where anxiety feeds into depression, it can literally make people want to die. How can that be evolutionarily adaptive?

Here it may be helpful to remember that in our ancestral environment, status and survival were oft one and the same. Humans are the most social organisms on Earth; I even sometimes describe us as hypersocial, a whole new category of social that no other organism seems to have achieved. We cooperate with others of our species on a mind-bogglingly grand scale, and are utterly dependent upon vast interconnected social systems far too large and complex for us to truly understand, let alone control.

At this historical epoch, these social systems are especially vast and incomprehensible; but at least for most of us in First World countries, they are also forgiving in a way that is fundamentally alien to our ancestors’ experience. It was not so long ago that a failed hunt or a bad harvest would let your family starve unless you could beseech your community for aid successfully—which meant that your very survival could depend upon being in the good graces of that community. But now we have food stamps, so even if everyone in your town hates you, you still get to eat. Of course some societies are more forgiving (Sweden) than others (the United States); and virtually all societies could be even more forgiving than they are. But even the relatively cutthroat competition of the US today has far less genuine risk of truly catastrophic failure than what most human beings lived through for most of our existence as a species.

I have found this realization helpful—hardly a cure, but helpful, at least: What are you really afraid of? When you feel anxious, your body often tells you that the stakes are overwhelming, life-or-death; but if you stop and think about it, in the world we live in today, that’s almost never true. Failing at one important task at work probably won’t get you fired—and even getting fired won’t really make you starve.

In fact, we might be less anxious if it were! For our bodies’ fear system seems to be optimized for the following scenario: An immediate threat with high chance of success and life-or-death stakes. Spear that wild animal, or jump over that chasm. It will either work or it won’t, you’ll know immediately; it probably will work; and if it doesn’t, well, that may be it for you. So you’d better not fail. (I think it’s interesting how much of our fiction and media involves these kinds of events: The hero would surely and promptly die if he fails, but he won’t fail, for he’s the hero! We often seem more comfortable in that sort of world than we do in the one we actually live in.)

Whereas the life we live in now is one of delayed consequences with low chance of success and minimal stakes. Send out a dozen job applications. Hear back in a week from three that want to interview you. Do those interviews and maybe one will make you an offer—but honestly, probably not. Next week do another dozen. Keep going like this, week after week, until finally one says yes. Each failure actually costs you very little—but you will fail, over and over and over and over.

In other words, we have transitioned from an environment of immediate return to one of delayed return.

The result is that a system which was optimized to tell us never fail or you will die is being put through situations where failure is constantly repeated. I think deep down there is a part of us that wonders, “How are you still alive after failing this many times?” If you had fallen in as many ravines as I have received rejection letters, you would assuredly be dead many times over.

Yet perhaps our brains are not quite as miscalibrated as they seem. Again I come back to the fact that anxiety always seems to be about people and evaluation; it’s different from immediate life-or-death fear. I actually experience very little life-or-death fear, which makes sense; I live in a very safe environment. But I experience anxiety almost constantly—which also makes a certain amount of sense, seeing as I live in an environment where I am being almost constantly evaluated by other people.

One theory posits that anxiety and depression are a dual mechanism for dealing with social hierarchy: You are anxious when your position in the hierarchy is threatened, and depressed when you have lost it. Primates like us do seem to care an awful lot about hierarchies—and I’ve written before about how this explains some otherwise baffling things about our economy.

But I for one have never felt especially invested in hierarchy. At least, I have very little desire to be on top of the hiearchy. I don’t want to be on the bottom (for I know how such people are treated); and I strongly dislike most of the people who are actually on top (for they’re most responsible for treating the ones on the bottom that way). I also have ‘a problem with authority’; I don’t like other people having power over me. But if I were to somehow find myself ruling the world, one of the first things I’d do is try to figure out a way to transition to a more democratic system. So it’s less like I want power, and more like I want power to not exist. Which means that my anxiety can’t really be about fearing to lose my status in the hierarchy—in some sense, I want that, because I want the whole hierarchy to collapse.

If anxiety involved the fear of losing high status, we’d expect it to be common among those with high status. Quite the opposite is the case. Anxiety is more common among people who are more vulnerable: Women, racial minorities, poor people, people with chronic illness. LGBT people have especially high rates of anxiety. This suggests that it isn’t high status we’re afraid of losing—though it could still be that we’re a few rungs above the bottom and afraid of falling all the way down.

It also suggests that anxiety isn’t entirely pathological. Our brains are genuinely responding to circumstances. Maybe they are over-responding, or responding in a way that is not ultimately useful. But the anxiety is at least in part a product of real vulnerabilities. Some of what we’re worried about may actually be real. If you cannot carry yourself with the confidence of a mediocre White man, it may be simply because his status is fundamentally secure in a way yours is not, and he has been afforded a great many advantages you never will be. He never had a Supreme Court ruling decide his rights.

I cannot offer you a cure for anxiety. I cannot even really offer you a complete explanation of where it comes from. But perhaps I can offer you this: It is not your fault. Your brain evolved for a very different world than this one, and it is doing its best to protect you from the very different risks this new world engenders. Hopefully one day we’ll figure out a way to get it calibrated better.