Sep 10 JDN 2460198

At the time of writing this post, I have officially submitted my letter of resignation at the University of Edinburgh. I’m giving them an entire semester of notice, so I won’t actually be leaving until December. But I have committed to my decision now, and that feels momentous.

Since my position here was temporary to begin with, I’m actually only leaving a semester early. Part of me wanted to try to stick it out, continue for that one last semester and leave on better terms. Until I sent that letter, I had that option. Now I don’t, and I feel a strange mix of emotions: Relief that I have finally made the decision, regret that it came to this, doubt about what comes next, and—above all—profound ambivalence.

Maybe it’s the very act of quitting—giving up, being a quitter—that feels bad. Even knowing that I need to get out of here, it hurts to have to be the one to quit.

Our society prizes grit and perseverance. Since I was a child I have been taught that these are virtues. And to some extent, they are; there certainly is such a thing as giving up too quickly.

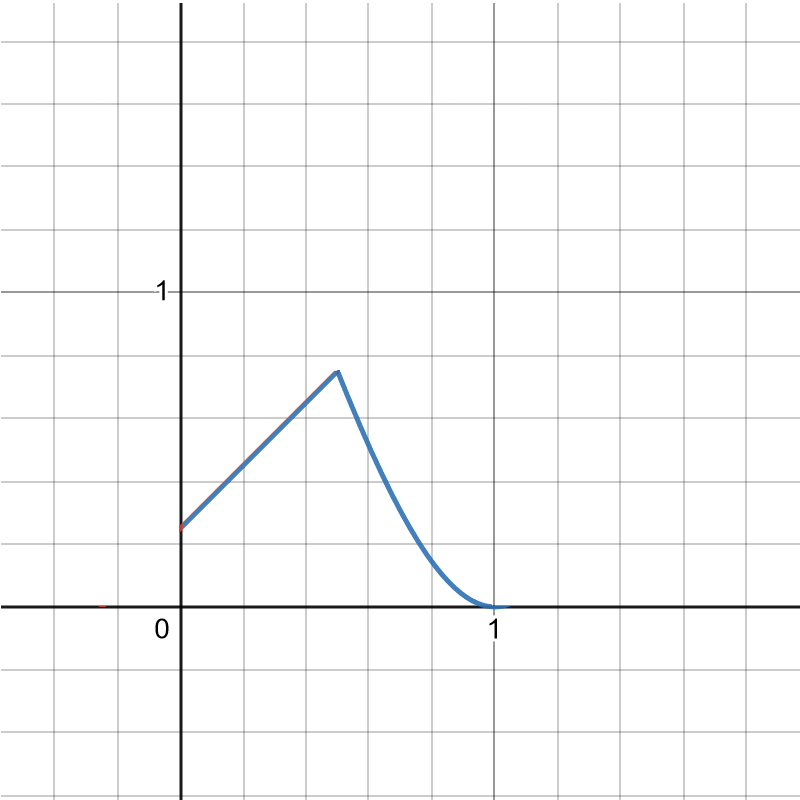

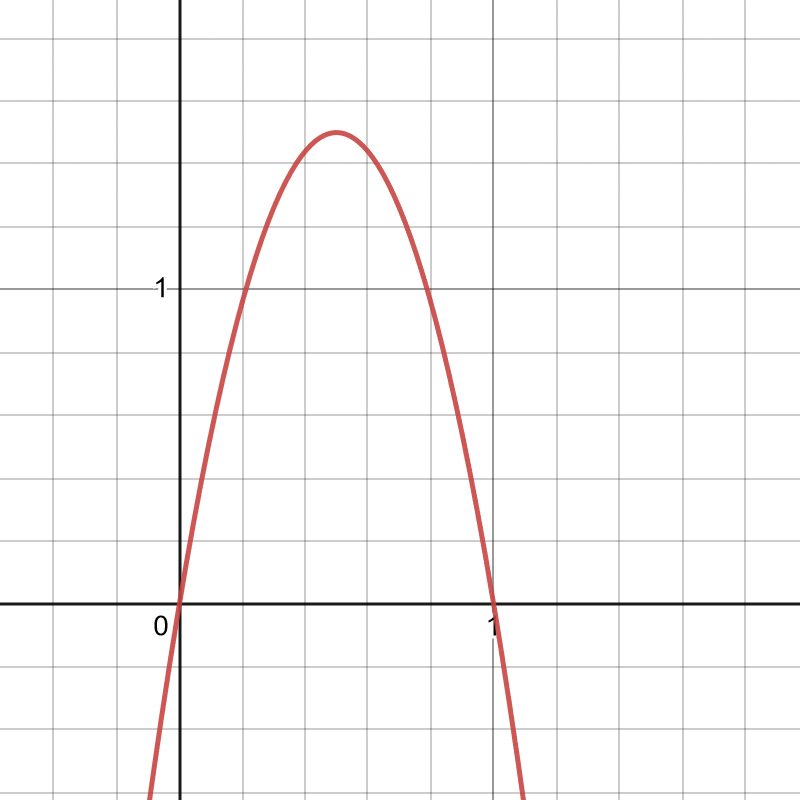

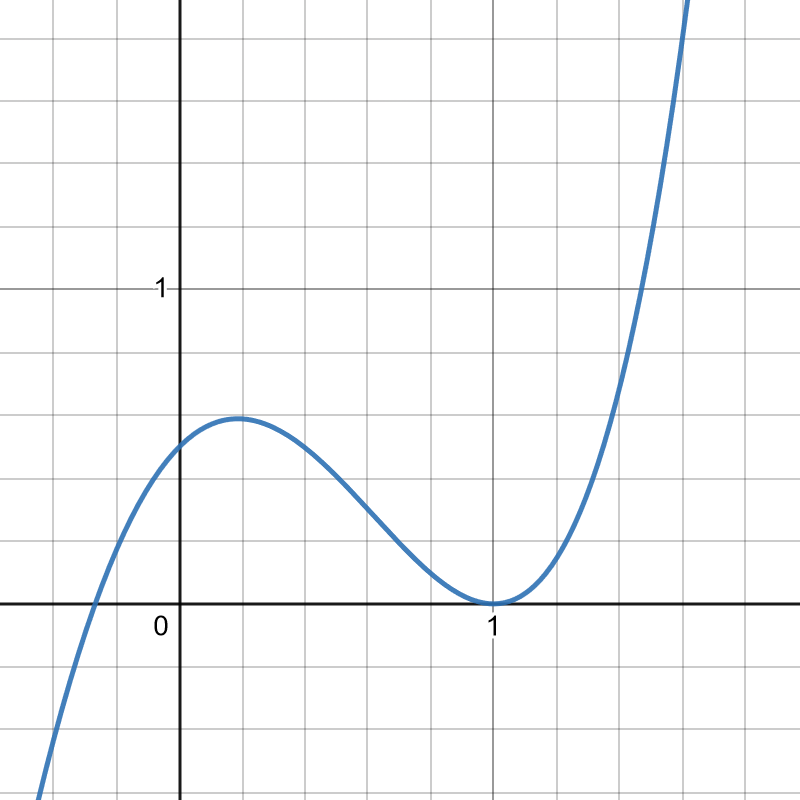

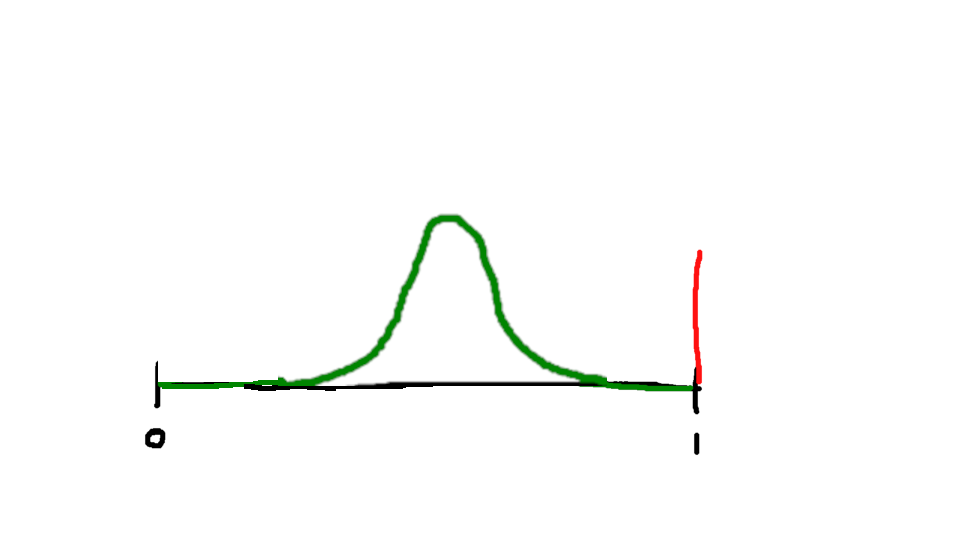

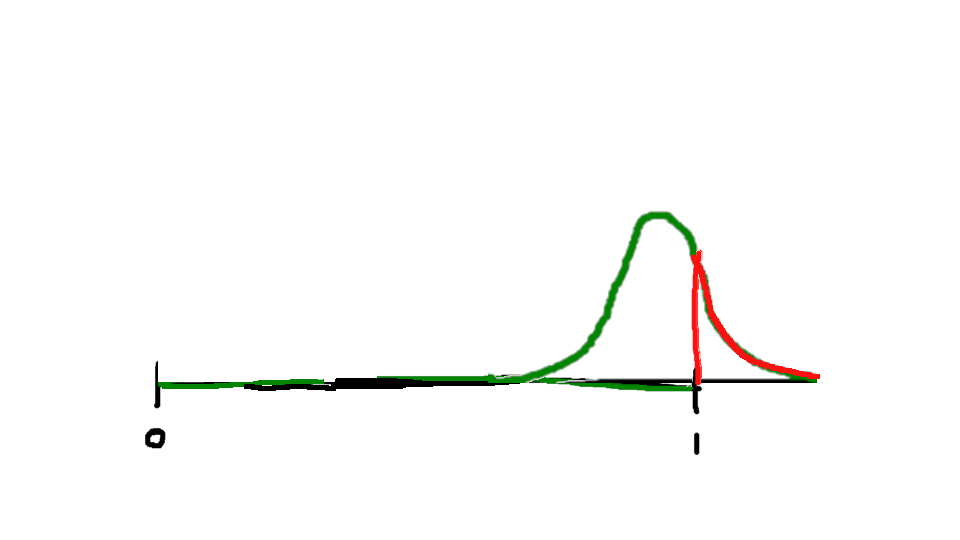

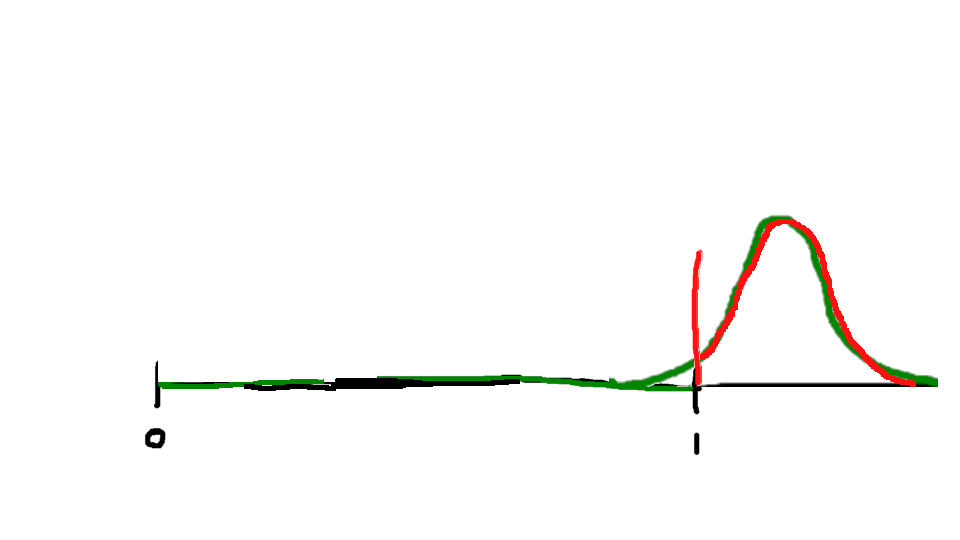

But there is also such a thing as not knowing when to quit. Sometimes things really aren’t going according to plan, and you need to quit before you waste even more time and effort. And I think I am like Randall Monroe in this regard; I am more inclined to stay when I shouldn’t than quit when I shouldn’t:

Sometimes quitting isn’t even as permanent as it is made out to be. In many cases, you can go back later and try again when you are better prepared.

In my case, I am unlikely to ever work at the University of Edinburgh again, but I haven’t yet given up on ever having a career in academia. Then again, I am by no means as certain as I once was that academia is the right path for me. I will definitely be searching for other options.

There is a reason we are so enthusiastically sold on the virtue of perseverance. Part of how our society sells the false narrative of meritocracy is by claiming that people who succeed did so because they tried harder or kept on trying.

This is not entirely false; all other things equal, you are more likely to succeed if you keep on trying. But in some ways that just makes it more seductive and insidious.

For the real reason most people hit home runs in life is they were born on third base. The vast majority of success in life is determined by circumstances entirely outside individual control.

Even having the resources to keep trying is not guaranteed for everyone. I remember a great post on social media pointing out that entrepreneurship is like one of those carnival games:

Entrepreneurship is like one of those carnival games where you throw darts or something.

Middle class kids can afford one throw. Most miss. A few hit the target and get a small prize. A very few hit the center bullseye and get a bigger prize. Rags to riches! The American Dream lives on.

Rich kids can afford many throws. If they want to, they can try over and over and over again until they hit something and feel good about themselves. Some keep going until they hit the center bullseye, then they give speeches or write blog posts about ‘meritocracy’ and the salutary effects of hard work.

Poor kids aren’t visiting the carnival. They’re the ones working it.

The odds of succeeding on any given attempt are slim—but you can always pay for more tries. A middle-class person can afford to try once; mostly those attempts will fail, but a few will succeed and then go on to talk about how their brilliant talent and hard work made the difference. A rich person can try as many times as they like, and when they finally succeed, they can credit their success to perseverance and a willingness to take risks. But the truth is, they didn’t have any exceptional reserves of grit or courage; they just had exceptional reserves of money.

In my case, I was not depleting money (if anything, I’m probably losing out financially by leaving early, though that very much depends on how the job market goes for me): It was something far more valuable. I was whittling away at my own mental health, depleting my energy, draining my motivation. The resource I was exhausting was my very soul.

I still have trouble articulating why it has been so painful for me to work here. It’s so hard to point to anything in particular.

The most obvious downsides were things I knew at the start: The position is temporary, the pay is mediocre, and I had to move across the Atlantic and live thousands of miles from home. And I had already heard plenty about the publish-or-perish system of research publication.

Other things seem like minor annoyances: They never did give me a good office (I have to share it with too many people, and there isn’t enough space, so in fact I rarely use it at all). They were supposed to assign me a faculty mentor and never did. They kept rearranging my class schedule and not telling me things until immediately beforehand.

I think what it really comes down to is I didn’t realize how much it would hurt. I knew that I was moving across the Atlantic—but I didn’t know how isolated and misunderstood I would feel when I did. I knew that publish-or-perish was a problem—but I didn’t know how agonizing it would be for me in particular. I knew I probably wouldn’t get very good mentorship from the other faculty—but I didn’t realize just how bad it would be, or how desperately I would need that support I didn’t get.

I either underestimated the severity of these problems, or overestimated my own resilience. I thought I knew what I was going into, and I thought I could take it. But I was wrong. I couldn’t take it. It was tearing me apart. My only answer was to leave.

So, leave I shall. I have now committed to doing so.

I don’t know what comes next. I don’t even know if I’ve made the right choice. Perhaps I’ll never truly know. But I made the choice, and now I have to live with it.