JDN 2457492

Much as you are officially a professional when people start paying you for what you do, I think you are officially a book reviewer when people start sending you books for free asking you to review them for publicity. This has now happened to me, with the book Equal Is Unfair by Don Watkins and Yaron Brook. This post is longer than usual, but in order to be fair to the book’s virtues as well as its flaws, I felt a need to explain quite thoroughly.

It’s a very frustrating book, because at times I find myself agreeing quite strongly with the first part of a paragraph, and then reaching the end of that same paragraph and wanting to press my forehead firmly into the desk in front of me. It makes some really good points, and for the most part uses economic statistics reasonably accurately—but then it rides gleefully down a slippery slope fallacy like a waterslide. But I guess that’s what I should have expected; it’s by leaders of the Ayn Rand Institute, and my experience with reading Ayn Rand is similar to that of Randall Monroe (I’m mainly referring to the alt-text, which uses slightly foul language).

As I kept being jostled between “That’s a very good point.”, “Hmm, that’s an interesting perspective.”, and “How can anyone as educated as you believe anything that stupid!?” I realized that there are actually three books here, interleaved:

1. A decent economics text on the downsides of taxation and regulation and the great success of technology and capitalism at raising the standard of living in the United States, which could have been written by just about any mainstream centrist neoclassical economist—I’d say it reads most like John Taylor or Ken Galbraith. My reactions to this book were things like “That’s a very good point.”, and “Sure, but any economist would agree with that.”

2. An interesting philosophical treatise on the meanings of “equality” and “opportunity” and their application to normative economic policy, as well as about the limitations of statistical data in making political and ethical judgments. It could have been written by Robert Nozick (actually I think much of it was based on Robert Nozick). Some of the arguments are convincing, others are not, and many of the conclusions are taken too far; but it’s well within the space of reasonable philosophical arguments. My reactions to this book were things like “Hmm, that’s an interesting perspective.” and “Your argument is valid, but I think I reject the second premise.”

3. A delusional rant of the sort that could only be penned by a True Believer in the One True Gospel of Ayn Rand, about how poor people are lazy moochers, billionaires are world-changing geniuses whose superior talent and great generosity we should all bow down before, and anyone who would dare suggest that perhaps Steve Jobs got lucky or owes something to the rest of society is an authoritarian Communist who hates all achievement and wants to destroy the American Dream. It was this book that gave me reactions like “How can anyone as educated as you believe anything that stupid!?” and “You clearly have no idea what poverty is like, do you?” and “[expletive] you, you narcissistic ingrate!”

Given that the two co-authors are Executive Director and a fellow of the Ayn Rand Institute, I suppose I should really be pleasantly surprised that books 1 and 2 exist, rather than disappointed by book 3.

As evidence of each of the three books interleaved, I offer the following quotations:

Book 1:

“All else being equal, taxes discourage production and prosperity.” (p. 30)

No reasonable economist would disagree. The key is all else being equal—it rarely is.

“For most of human history, our most pressing problem was getting enough food. Now food is abundant and affordable.” (p.84)

Correct! And worth pointing out, especially to anyone who thinks that economic progress is an illusion or we should go back to pre-industrial farming practices—and such people do exist.

“Wealth creation is first and foremost knowledge creation. And this is why you can add to the list of people who have created the modern world, great thinkers: people such as Euclid, Aristotle, Galileo, Newton, Darwin, Einstein, and a relative handful of others.” (p.90, emph. in orig.)

Absolutely right, though as I’ll get to below there’s something rather notable about that list.

“To be sure, there is competition in an economy, but it’s not a zero-sum game in which some have to lose so that others can win—not in the big picture.” (p. 97)

Yes! Precisely! I wish I could explain to more people—on both the Left and the Right, by the way—that economics is nonzero-sum, and that in the long run competitive markets improve the standard of living of society as a whole, not just the people who win that competition.

Book 2:

“Even opportunities that may come to us without effort on our part—affluent parents, valuable personal connections, a good education—require enormous effort to capitalize on.” (p. 66)

This is sometimes true, but clearly doesn’t apply to things like the Waltons’ inherited billions, for which all they had to do was be born in the right family and not waste their money too extravagantly.

“But life is not a game, and achieving equality of initial chances means forcing people to play by different rules.” (p. 79)

This is an interesting point, and one that I think we should acknowledge; we must treat those born rich differently from those born poor, because their unequal starting positions mean that treating them equally from this point forward would lead to a wildly unfair outcome. If my grandfather stole your grandfather’s wealth and passed it on to me, the fair thing to do is not to treat you and I equally from this point forward—it’s to force me to return what was stolen, insofar as that is possible. And even if we suppose that my grandfather earned far vaster wealth than yours, I think a more limited redistribution remains justified simply to put you and I on a level playing field and ensure fair competition and economic efficiency.

“The key error in this argument is that it totally mischaracterizes what it means to earn something. For the egalitarians, the results of our actions don’t merely have to be under our control, but entirely of our own making. […] But there is nothing like that in reality, and so what the egalitarians are ultimately doing is wiping out the very possibility of earning something.” (p. 193)

The way they use “egalitarian” as an insult is a bit grating, but there clearly are some actual egalitarian philosophers whose views are this extreme, such as G.A. Cohen, James Kwak and Peter Singer. I strongly agree that we need to make a principled distinction between gains that are earned and gains that are unearned, such that both sets are nonempty. Yet while Cohen would seem to make “earned” an empty set, Watkins and Brook very nearly make “unearned” empty—you get what you get, and you deserve it. The only exceptions they seem willing to make are outright theft and, what they consider equivalent, taxation. They have no concept of exploitation, excessive market power, or arbitrage—and while they claim they oppose fraud, they seem to think that only government is capable of it.

Book 3:

“What about government handouts (usually referred to as ‘transfer payments’)?” (p. 23)

Because Social Security is totally just a handout—it’s not like you pay into it your whole life or anything.

“No one cares whether the person who fixes his car or performs his brain surgery or applies for a job at his company is male or female, Indian or Pakistani—he wants to know whether they are competent.” (p.61)

Yes they do. We have direct experimental evidence of this.

“The notion that ‘spending drives the economy’ and that rich people spend less than others isn’t a view seriously entertained by economists,[…]” (p. 110)

The New Synthesis is Keynesian! This is what Milton Friedman was talking about when he said, “We’re all Keynesians now.”

“Because mobility statistics don’t distinguish between those who don’t rise and those who can’t, they are useless when it comes to assessing how healthy mobility is.” (p. 119)

So, if Black people have much lower odds of achieving high incomes even controlling for education, we can’t assume that they are disadvantaged or discriminated against; maybe Black people are just lazy or stupid? Is that what you’re saying here? (I think it might be.)

“Payroll taxes alone amount to 15.3 percent of your income; money that is taken from you and handed out to the elderly. This means that you have to spend more than a month and a half each year working without pay in order to fund other people’s retirement and medical care.” (p. 127)

That is not even close to how taxes work. Taxes are not “taken” from money you’d otherwise get—taxation changes prices and the monetary system depends upon taxation.

“People are poor, in the end, because they have not created enough wealth to make themselves prosperous.” (p. 144)

This sentence was so awful that when I showed it to my boyfriend, he assumed it must be out of context. When I showed him the context, he started swearing the most I’ve heard him swear in a long time, because the context was even worse than it sounds. Yes, this book is literally arguing that the reason people are poor is that they’re just too lazy and stupid to work their way out of poverty.

“No society has fully implemented the egalitarian doctrine, but one came as close as any society can come: Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge.” (p. 207)

Because obviously the problem with the Khmer Rouge was their capital gains taxes. They were just too darn fair, and if they’d been more selfish they would never have committed genocide. (The authors literally appear to believe this.)

So there are my extensive quotations, to show that this really is what the book is saying. Now, a little more summary of the good, the bad, and the ugly.

One good thing is that the authors really do seem to understand fairly well the arguments of their opponents. They quote their opponents extensively, and only a few times did it feel meaningfully out of context. Their use of economic statistics is also fairly good, though occasionally they present misleading numbers or compare two obviously incomparable measures.

One of the core points in Equal is Unfair is quite weak: They argue against the “shared-pie assumption”, which is that we create wealth as a society, and thus the rest of society is owed some portion of the fruits of our efforts. They maintain that this is fundamentally authoritarian and immoral; essentially they believe a totalizing false dichotomy between either absolute laissez-faire or Stalinist Communism.

But the “shared-pie assumption” is not false; we do create wealth as a society. Human cognition is fundamentally social cognition; they said themselves that we depend upon the discoveries of people like Newton and Einstein for our way of life. But it should be obvious we can never pay Einstein back; so instead we must pay forward, to help some child born in the ghetto to rise to become the next Einstein. I agree that we must build a society where opportunity is maximized—and that means, necessarily, redistributing wealth from its current state of absurd and immoral inequality.

I do however agree with another core point, which is that most discussions of inequality rely upon a tacit assumption which is false: They call it the “fixed-pie assumption”.

When you talk about the share of income going to different groups in a population, you have to be careful about the fact that there is not a fixed amount of wealth in a society to be distributed—not a “fixed pie” that we are cutting up and giving around. If it were really true that the rising income share of the top 1% were necessary to maximize the absolute benefits of the bottom 99%, we probably should tolerate that, because the alternative means harming everyone. (In arguing this they quote John Rawls several times with disapprobation, which is baffling because that is exactly what Rawls says.)

Even if that’s true, there is still a case to be made against inequality, because too much wealth in the hands of a few people will give them more power—and unequal power can be dangerous even if wealth is earned, exchanges are uncoerced, and the distribution is optimally efficient. (Watkins and Brook dismiss this contention out of hand, essentially defining beneficent exploitation out of existence.)

Of course, in the real world, there’s no reason to think that the ballooning income share of the top 0.01% in the US is actually associated with improved standard of living for everyone else.

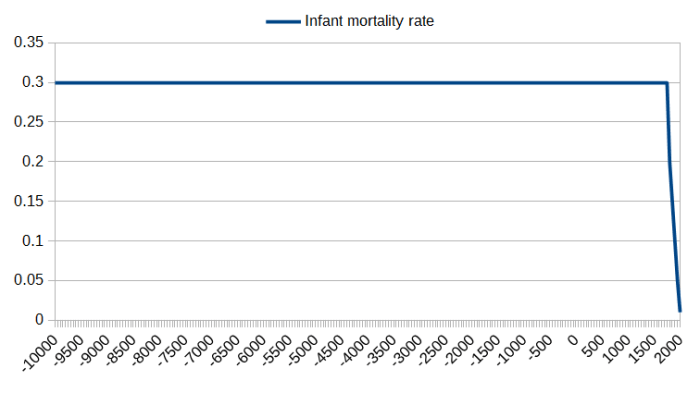

I’ve shown these graphs before, but they bear repeating:

Income shares for the top 1% and especially the top 0.1% and 0.01% have risen dramatically in the last 30 years.

But real median income has only slightly increased during the same period.

Thus, mean income has risen much faster than median income.

While theoretically it could be that the nature of our productivity technology has shifted in such a way that it suddenly became necessary to heap more and more wealth on the top 1% in order to continue increasing national output, there is actually very little evidence of this. On the contrary, as Joseph Stiglitz (Nobel Laureate, you may recall) has documented, the leading cause of our rising inequality appears to be a dramatic increase in rent-seeking, which is to say corruption, exploitation, and monopoly power. (This probably has something to do with why I found in my master’s thesis that rising top income shares correlate quite strongly with rising levels of corruption.)

Now to be fair, the authors of Equal is Unfair do say that they are opposed to rent-seeking, and would like to see it removed. But they have a very odd concept of what rent-seeking entails, and it basically seems to amount to saying that whatever the government does is rent-seeking, whatever corporations do is fair free-market competition. On page 38 they warn us not to assume that government is good and corporations are bad—but actually it’s much more that they assume that government is bad and corporations are good. (The mainstream opinion appears to be actually that both are bad, and we should replace them both with… er… something.)

They do make some other good points I wish more leftists would appreciate, such as the point that while colonialism and imperialism can damage countries that suffer them and make them poorer, they generally do not benefit the countries that commit them and make them richer. The notion that Europe is rich because of imperialism is simply wrong; Europe is rich because of education, technology, and good governance. Indeed, the greatest surge in Europe’s economic growth occurred as the period of imperialism was winding down—when Europeans realized that they would be better off trying to actually invent and produce things rather than stealing them from others.

Likewise, they rightfully demolish notions of primitivism and anti-globalization that I often see bouncing around from folks like Naomi Klein. But these are book 1 messages; any economist would agree that primitivism is a terrible idea, and very few are opposed to globalization per se.

The end of Equal is Unfair gives a five-part plan for unleashing opportunity in America:

1. Abolish all forms of corporate welfare so that no business can gain unfair advantage.

2. Abolish government barriers to work so that every individual can enjoy the dignity of earned success.

3. Phase out the welfare state so that America can once again become the land of self-reliance.

4. Unleash the power of innovation in education by ending the government monopoly on schooling.

5. Liberate innovators from the regulatory shackles that are strangling them.

Number 1 is hard to disagree with, except that they include literally everything the government does that benefits a corporation as corporate welfare, including things like subsidies for solar power that the world desperately needs (or millions of people will die).

Number 2 sounds really great until you realize that they are including all labor standards, environmental standards and safety regulations as “barriers to work”; because it’s such a barrier for children to not be able to work in a factory where your arm can get cut off, and such a barrier that we’ve eliminated lead from gasoline emissions and thereby cut crime in half.

Number 3 could mean a lot of things; if it means replacing the existing system with a basic income I’m all for it. But in fact it seems to mean removing all social insurance whatsoever. Indeed, Watkins and Brook do not appear to believe in social insurance at all. The whole concept of “less fortunate”, “there but for the grace of God go I” seems to elude them. They have no sense that being fortunate in their own lives gives them some duty to help others who were not; they feel no pang of moral obligation whatsoever to help anyone else who needs help. Indeed, they literally mock the idea that human beings are “all in this together”.

They also don’t even seem to believe in public goods, or somehow imagine that rational self-interest could lead people to pay for public goods without any enforcement whatsoever despite the overwhelming incentives to free-ride. (What if you allow people to freely enter a contract that provides such enforcement mechanisms? Oh, you mean like social democracy?)

Regarding number 4, I’d first like to point out that private schools exist. Moreover, so do charter schools in most states, and in states without charter schools there are usually vouchers parents can use to offset the cost of private schools. So while the government has a monopoly in the market share sense—the vast majority of education in the US is public—it does not actually appear to be enforcing a monopoly in the anti-competitive sense—you can go to private school, it’s just too expensive or not as good. Why, it’s almost as if education is a public good or a natural monopoly.

Number 5 also sounds all right, until you see that they actually seem most opposed to antitrust laws of all things. Why would antitrust laws be the ones that bother you? They are designed to increase competition and lower barriers, and largely succeed in doing so (when they are actually enforced, which is rare of late). If you really want to end barriers to innovation and government-granted monopolies, why is it not patents that draw your ire?

They also seem to have trouble with the difference between handicapping and redistribution—they seem to think that the only way to make outcomes more equal is to bring the top down and leave the bottom where it is, and they often use ridiculous examples like “Should we ban reading to your children, because some people don’t?” But of course no serious egalitarian would suggest such a thing. Education isn’t fungible, so it can’t be redistributed. You can take it away (and sometimes you can add it, e.g. public education, which Watkins and Brooks adamantly oppose); but you can’t simply transfer it from one person to another. Money on the other hand, is by definition fungible—that’s kind of what makes it money, really. So when we take a dollar from a rich person and give it to a poor person, the poor person now has an extra dollar. We’ve not simply lowered; we’ve also raised. (In practice it’s a bit more complicated than that, as redistribution can introduce inefficiencies. So realistically maybe we take $1.00 and give $0.90; that’s still worth doing in a lot of cases.)

If attributes like intelligence were fungible, I think we’d have a very serious moral question on our hands! It is not obvious to me that the world is better off with its current range of intelligence, compared to a world where geniuses had their excess IQ somehow sucked out and transferred to mentally disabled people. Or if you think that the marginal utility of intelligence is increasing, then maybe we should redistribute IQ upward—take it from some mentally disabled children who aren’t really using it for much and add it onto some geniuses to make them super-geniuses. Of course, the whole notion is ridiculous; you can’t do that. But whereas Watkins and Brook seem to think it’s obvious that we shouldn’t even if we could, I don’t find that obvious at all. You didn’t earn your IQ (for the most part); you don’t seem to deserve it in any deep sense; so why should you get to keep it, if the world would be much better off if you didn’t? Why should other people barely be able to feed themselves so I can be good at calculus? At best, maybe I’m free to keep it—but given the stakes, I’m not even sure that would be justifiable. Peter Singer is right about one thing: You’re not free to let a child drown in a lake just to keep your suit from getting wet.

Ultimately, if you really want to understand what’s going on with Equal is Unfair, consider the following sentence, which I find deeply revealing as to the true objectives of these Objectivists:

“Today, meanwhile, although we have far more liberty than our feudal ancestors, there are countless ways in which the government restricts our freedom to produce and trade including minimum wage laws, rent control, occupational licensing laws, tariffs, union shop laws, antitrust laws, government monopolies such as those granted to the post office and education system, subsidies for industries such as agriculture or wind and solar power, eminent domain laws, wealth redistribution via the welfare state, and the progressive income tax.” (p. 114)

Some of these are things no serious economist would disagree with: We should stop subsidizing agriculture and tariffs should be reduced or removed. Many occupational licenses are clearly unnecessary (though this has a very small impact on inequality in real terms—licensing may stop you from becoming a barber, but it’s not what stops you from becoming a CEO). Others are legitimately controversial: Economists are currently quite divided over whether minimum wage is beneficial or harmful (I lean toward beneficial, but I’d prefer a better solution), as well as how to properly regulate unions so that they give workers much-needed bargaining power without giving unions too much power. But a couple of these are totally backward, exactly contrary to what any mainstream economist would say: Antitrust laws need to be enforced more, not eliminated (don’t take it from me; take it from that well-known Marxist rag The Economist). Subsidies for wind and solar power make the economy more efficient, not less—and suspiciously Watkins and Brook omitted the competing subsidies that actually are harmful, namely those to coal and oil.

Moreover, I think it’s very revealing that they included the word progressive when talking about taxation. In what sense does making a tax progressive undermine our freedom? None, so far as I can tell. The presence of a tax undermines freedom—your freedom to spend that money some other way. Making the tax higher undermines freedom—it’s more money you lose control over. But making the tax progressive increases freedom for some and decreases it for others—and since rich people have lower marginal utility of wealth and are generally more free in substantive terms in general, it really makes the most sense that, holding revenue constant, making a tax progressive generally makes your people more free.

But there’s one thing that making taxes progressive does do: It benefits poor people and hurts rich people. And thus the true agenda of Equal is Unfair becomes clear: They aren’t actually interested in maximizing freedom—if they were, they wouldn’t be complaining about occupational licensing and progressive taxation, they’d be outraged by forced labor, mass incarceration, indefinite detention, and the very real loss of substantive freedom that comes from being born into poverty. They wouldn’t want less redistribution, they’d want more efficient and transparent redistribution—a shift from the current hodgepodge welfare state to a basic income system. They would be less concerned about the “freedom” to pollute the air and water with impunity, and more concerned about the freedom to breathe clean air and drink clean water.

No, what they really believe is rich people are better. They believe that billionaires attained their status not by luck or circumstance, not by corruption or ruthlessness, but by the sheer force of their genius. (This is essentially the entire subject of chapter 6, “The Money-Makers and the Money-Appropriators”, and it’s nauseating.) They describe our financial industry as “fundamentally moral and productive” (p.156)—the industry that you may recall stole millions of homes and laundered money for terrorists. They assert that no sane person could believe that Steve Wozniack got lucky—I maintain no sane person could think otherwise. Yes, he was brilliant; yes, he invented good things. But he had to be at the right place at the right time, in a society that supported and educated him and provided him with customers and employees. You didn’t build that.

Indeed, perhaps most baffling is that they themselves seem to admit that the really great innovators, such as Newton, Einstein, and Darwin, were scientists—but scientists are almost never billionaires. Even the common counterexample, Thomas Edison, is largely false; he mainly plagiarized from Nikola Tesla and appropriated the ideas of his employees. Newton, Einstein and Darwin were all at least upper-middle class (as was Tesla, by the way—he did not die poor as is sometimes portrayed), but they weren’t spectacularly mind-bogglingly rich the way that Steve Jobs and Andrew Carnegie were and Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos are.

Some people clearly have more talent than others, and some people clearly work harder than others, and some people clearly produce more than others. But I just can’t wrap my head around the idea that a single man can work so hard, be so talented, produce so much that he can deserve to have as much wealth as a nation of millions of people produces in a year. Yet, Mark Zuckerberg has that much wealth. Remind me again what he did? Did he cure a disease that was killing millions? Did he colonize another planet? Did he discover a fundamental law of nature? Oh yes, he made a piece of software that’s particularly convenient for talking to your friends. Clearly that is worth the GDP of Latvia. Not that silly Darwin fellow, who only uncovered the fundamental laws of life itself.

In the grand tradition of reducing complex systems to simple numerical values, I give book 1 a 7/10, book 2 a 5/10, and book 3 a 2/10. Equal is Unfair is about 25% book 1, 25% book 2, and 50% book 3, so altogether their final score is, drumroll please: 4/10. Maybe read the first half, I guess? That’s where most of the good stuff is.