Jul 27 JDN 2460884

For the last few weeks I’ve been working at a golf course. (It’s a bit of an odd situation: I’m not actually employed by the golf course; I’m contracted by a nonprofit to be a “job coach” for a group of youths who are part of a work program that involves them working at the golf course.)

I hate golf. I have always hated golf. I find it boring and pointless—which, to be fair, is my reaction to most sports—and also an enormous waste of land and water. A golf course is also a great place for oligarchs to arrange collusion.

But I noticed something about being on the golf course every day, seeing people playing and working there: I feel like I hate it a bit less now.

This is almost certainly a mere-exposure effect: Simply being exposed to something many times makes it feel familiar, and that tends to make you like it more, or at least dislike it less. (There are some exceptions: repeated exposure to trauma can actually make you more sensitive to it, hating it even more.)

I kinda thought this would happen. I didn’t really want it to happen, but I thought it would.

This is very interesting from the perspective of Bayesian reasoning, because it is a theorem (though I cannot seem to find anyone naming the theorem; it’s like a folk theorem, I guess?) of Bayesian logic that the following is true:

The prior expectation of the posterior is the expectation of the prior.

The prior is what you believe before observing the evidence; the posterior is what you believe afterward. This theorem describes a relationship that holds between them.

This theorem means that, if I am being optimally rational, I should take into account all expected future evidence, not just evidence I have already seen. I should not expect to encounter evidence that will change my beliefs—if I did expect to see such evidence, I should change my beliefs right now!

This might be easier to grasp with an example.

Suppose I am trying to predict whether it will rain at 5:00 pm tomorrow, and I currently estimate that the probability of rain is 30%. This is my prior probability.

What will actually happen tomorrow is that it will rain or it won’t; so my posterior probability will either be 100% (if it rains) or 0% (if it doesn’t). But I had better assign a 30% chance to the event that will make me 100% certain it rains (namely, I see rain), and a 70% chance to the event that will make me 100% certain it doesn’t rain (namely, I see no rain); if I were to assign any other probabilities, then I must not really think the probability of rain at 5:00 pm tomorrow is 30%.

(The keen Bayesian will notice that the expected variance of my posterior need not be the variance of my prior: My initial variance is relatively high (it’s actually 0.3*0.7 = 0.21, because this is a Bernoulli distribution), because I don’t know whether it will rain or not; but my posterior variance will be 0, because I’ll know the answer once it rains or doesn’t.)

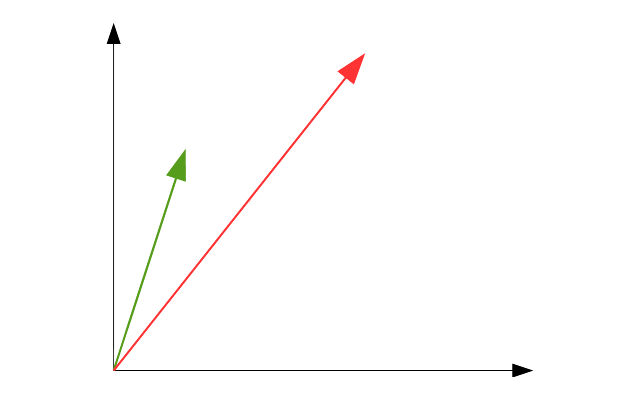

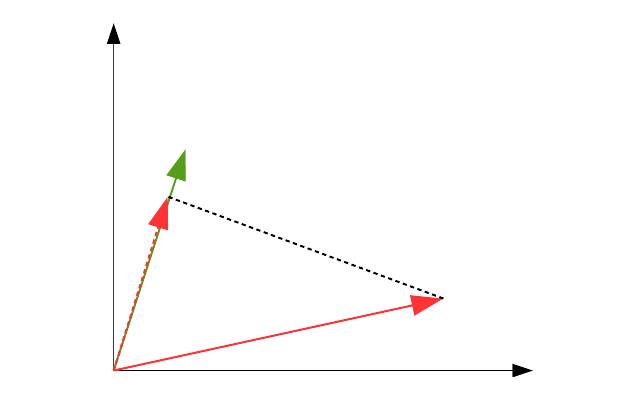

It’s a bit trickier to analyze, but this also works even if the evidence won’t make me certain. Suppose I am trying to determine the probability that some hypothesis is true. If I expect to see any evidence that might change my beliefs at all, then I should, on average, expect to see just as much evidence making me believe the hypothesis more as I see evidence that will make me believe the hypothesis less. If that is not what I expect, I should really change how much I believe the hypothesis right now!

So what does this mean for the golf example?

Was I wrong to hate golf quite so much before, because I knew that spending time on a golf course might make me hate it less?

I don’t think so.

See, the thing is: I know I’m not perfectly rational.

If I were indeed perfectly rational, then anything I expect to change my beliefs is a rational Bayesian update, and I should indeed factor it into my prior beliefs.

But if I know for a fact that I am not perfectly rational, that there are things which will change my beliefs in ways that make them deviate from rational Bayesian updating, then in fact I should not take those expected belief changes into account in my prior beliefs—since I expect to be wrong later, updating on that would just make me wrong now as well. I should only update on the expected belief changes that I believe will be rational.

This is something that a boundedly-rational person should do that neither a perfectly-rational nor perfectly-irrational person would ever do!

But maybe you don’t find the golf example convincing. Maybe you think I shouldn’t hate golf so much, and it’s not irrational for me to change my beliefs in that direction.

Very well. Let me give you a thought experiment which provides a very clear example of a time when you definitely would think your belief change was irrational.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting the two situations are in any way comparable; the golf thing is pretty minor, and for the thought experiment I’m intentionally choosing something quite extreme.

Here’s the thought experiment.

A mad scientist offers you a deal: Take this pill and you will receive $50 million. Naturally, you ask what the catch is. The catch, he explains, is that taking the pill will make you staunchly believe that the Holocaust didn’t happen. Take this pill, and you’ll be rich, but you’ll become a Holocaust denier. (I have no idea if making such a pill is even possible, but it’s a thought experiment, so bear with me. It’s certainly far less implausible than Swampman.)

I will assume that you are not, and do not want to become, a Holocaust denier. (If not, I really don’t know what else to say to you right now. It happened.) So if you take this pill, your beliefs will change in a clearly irrational way.

But I still think it’s probably justifiable to take the pill. This is absolutely life-changing money, for one thing, and being a random person who is a Holocaust denier isn’t that bad in the scheme of things. (Maybe it would be worse if you were in a position to have some kind of major impact on policy.) In fact, before taking the pill, you could write out a contract with a trusted friend that will force you to donate some of the $50 million to high-impact charities—and perhaps some of it to organizations that specifically fight Holocaust denial—thus ensuring that the net benefit to humanity is positive. Once you take the pill, you may be mad about the contract, but you’ll still have to follow it, and the net benefit to humanity will still be positive as reckoned by your prior, more correct, self.

It’s certainly not irrational to take the pill. There are perfectly-reasonable preferences you could have (indeed, likely dohave) that would say that getting $50 million is more important than having incorrect beliefs about a major historical event.

And if it’s rational to take the pill, and you intend to take the pill, then of course it’s rational to believe that in the future, you will have taken the pill and you will become a Holocaust denier.

But it would be absolutely irrational for you to become a Holocaust denier right now because of that. The pill isn’t going to provide evidence that the Holocaust didn’t happen (for no such evidence exists); it’s just going to alter your brain chemistry in such a way as to make you believe that the Holocaust didn’t happen.

So here we have a clear example where you expect to be more wrong in the future.

Of course, if this really only happens in weird thought experiments about mad scientists, then it doesn’t really matter very much. But I contend it happens in reality all the time:

- You know that by hanging around people with an extremist ideology, you’re likely to adopt some of that ideology, even if you really didn’t want to.

- You know that if you experience a traumatic event, it is likely to make you anxious and fearful in the future, even when you have little reason to be.

- You know that if you have a mental illness, you’re likely to form harmful, irrational beliefs about yourself and others whenever you have an episode of that mental illness.

Now, all of these belief changes are things you would likely try to guard against: If you are a researcher studying extremists, you might make a point of taking frequent vacations to talk with regular people and help yourself re-calibrate your beliefs back to normal. Nobody wants to experience trauma, and if you do, you’ll likely seek out therapy or other support to help heal yourself from that trauma. And one of the most important things they teach you in cognitive-behavioral therapy is how to challenge and modify harmful, irrational beliefs when they are triggered by your mental illness.

But these guarding actions only make sense precisely because the anticipated belief change is irrational. If you anticipate a rational change in your beliefs, you shouldn’t try to guard against it; you should factor it into what you already believe.

This also gives me a little more sympathy for Evangelical Christians who try to keep their children from being exposed to secular viewpoints. I think we both agree that having more contact with atheists will make their children more likely to become atheists—but we view this expected outcome differently.

From my perspective, this is a rational change, and it’s a good thing, and I wish they’d factor it into their current beliefs already. (Like hey, maybe if talking to a bunch of smart people and reading a bunch of books on science and philosophy makes you think there’s no God… that might be because… there’s no God?)

But I think, from their perspective, this is an irrational change, it’s a bad thing, the children have been “tempted by Satan” or something, and thus it is their duty to protect their children from this harmful change.

Of course, I am not a subjectivist. I believe there’s a right answer here, and in this case I’m pretty sure it’s mine. (Wouldn’t I always say that? No, not necessarily; there are lots of matters for which I believe that there are experts who know better than I do—that’s what experts are for, really—and thus if I find myself disagreeing with those experts, I try to educate myself more and update my beliefs toward theirs, rather than just assuming they’re wrong. I will admit, however, that a lot of people don’t seem to do this!)

But this does change how I might tend to approach the situation of exposing their children to secular viewpoints. I now understand better why they would see that exposure as a harmful thing, and thus be resistant to actions that otherwise seem obviously beneficial, like teaching kids science and encouraging them to read books. In order to get them to stop “protecting” their kids from the free exchange of ideas, I might first need to persuade them that introducing some doubt into their children’s minds about God isn’t such a terrible thing. That sounds really hard, but it at least clearly explains why they are willing to fight so hard against things that, from my perspective, seem good. (I could also try to convince them that exposure to secular viewpoints won’t make their kids doubt God, but the thing is… that isn’t true. I’d be lying.)

That is, Evangelical Christians are not simply incomprehensibly evil authoritarians who hate truth and knowledge; they quite reasonably want to protect their children from things that will harm them, and they firmly believe that being taught about evolution and the Big Bang will make their children more likely to suffer great harm—indeed, the greatest harm imaginable, the horror of an eternity in Hell. Convincing them that this is not the case—indeed, ideally, that there is no such place as Hell—sounds like a very tall order; but I can at least more keenly grasp the equilibrium they’ve found themselves in, where they believe that anything that challenges their current beliefs poses a literally existential threat. (Honestly, as a memetic adaptation, this is brilliant. Like a turtle, the meme has grown itself a nigh-impenetrable shell. No wonder it has managed to spread throughout the world.)