Sep 1 JDN 2458729

As you probably already know, the Amazon rainforest is currently on fire. You can get more details about the fires from The Washington Post, or CNN, or New York magazine, or even The Economist; but I think the best coverage I’ve seen has been these two articles from Al-Jazeera.

I have good news and bad news. Let’s start with the bad news: If we lose the Amazon, we lose everything. The ecological importance of the Amazon is basically impossible to overstate. The Amazon produces 20% of the oxygen on Earth. 25% of the carbon absorbed on land is absorbed by the Amazon. We must protect the Amazon, at almost any cost: Given how vital preserving the rainforest will be to resisting climate change, millions of lives are at stake.

The good news is there is still a lot of Amazon left.

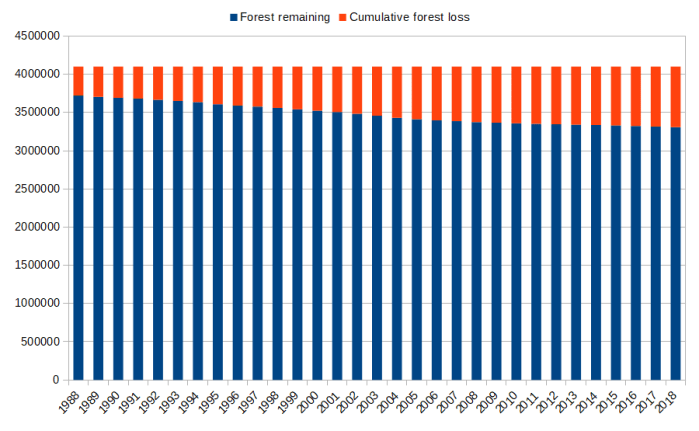

This graph shows the total cumulative deforestation of the Amazon, compared against its current area and its original area. The units are square kilometers; the Amazon rainforest has been reduced from 4.1 million square kilometers (1.6 million square miles) to 3.3 million hectares (1.3 million square miles), a decline of about 20% (21 log points). We still have four-fifths of the rainforest remaining—less than we should, but a lot more than we might.

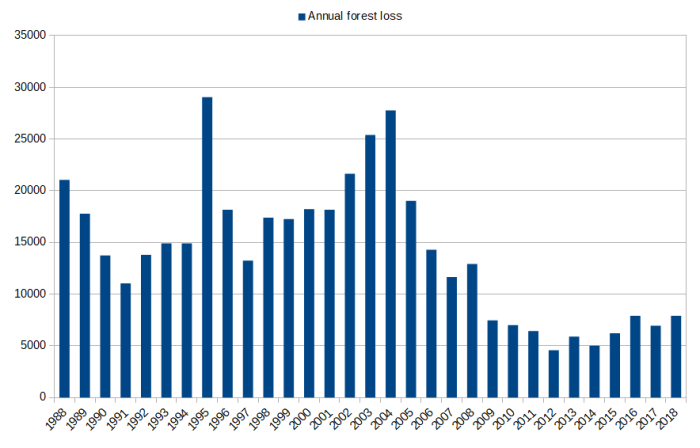

This graph shows the annual deforestation of the Amazon, with results that are even more encouraging. While the last few years have had faster deforestation than previously, we are still nowhere near the peak deforestation rates of the early 2000s. At peak deforestation, the Amazon was projected to last no more than 150 years; but at current rates of deforestation, the Amazon would not be completely destroyed in more than 400 years.

Of course, any loss of the Amazon is bad. We should actually be trying to restore the Amazon—that extra 800,000 square kilometers of high-density forest would sequester a lot of carbon. We probably can’t actually add the 9 million square kilometers (3.4 million square miles) of forest it would take to stop climate change; but any reforestation we do manage will help.

And a number of ecologists have been sounding the alarm that the Amazon is approaching some sort of tipping point where it will stop being a rainforest and become a savannah. If this happens, it may be irreversible. It sounds crazy to me—80% of the forest is still there!—but that’s what ecologists are saying, and I’ll defer to their expertise.

On the other hand, ecologists have been panicking about “irreversible tipping points” on almost everything for the past century. We really can’t be blamed for not taking their word as gospel: They’ve cried wolf about “population bombs” and shortages of food and water for a very long time now. So far their projections on the rates of temperature rise, species extinction, and deforestation have been quite accurate; but their predictions of dire human consequences have always suspiciously failed to materialize. Humans are quite creative and resilient, as it turns out. This is part of why I’m not actually afraid climate change will cause the collapse of human civilization (much less the utterly laughable claim of human extinction); but tens of millions of deaths is still plenty of reason to take drastic action.

Indeed, I think panicking is precisely what we need to avoid. If we exaggerate the problem to the point where it sounds hopeless, that won’t encourage people to take action; it may actually cause them to throw in the towel.

What do we actually need to do here? We need to restore as many forests as possible, and we need to cut carbon emissions as rapidly as possible.

This doesn’t require a revolution to overthrow capitalism. It doesn’t require exotic new technologies (though fusion power and improved electricity storage would certainly help). It simply requires a real commitment to bear real economic costs today in order to prevent much higher costs in the future.

Bernie Sanders has a climate change plan that is estimated to cost $16 trillion over the next ten years. Make no mistake: This is an enormous amount of money. US GDP is about $20 trillion, growing at about 3% per year, so we’re looking at about 6% of GDP over that interval. This is about twice our current military budget, or about our military budget in the 1980s. Notably, it is nowhere near the levels of military spending we reached in the Second World War, which exceeded 40% of GDP. That’s what happens when America really commits to something.

Would this be enough? The UN seems to think so. They estimate that it would cost about 1% of global GDP to keep global warming below 2 C. Even if that’s an underestimate, 6% of the GDP of the US and EU would by itself account for twice that amount—and I have no doubt that if America committed to climate change mitigation, Europe would gladly follow.

And it’s not as if this money would be set on fire. (Military spending, on the other hand, almost literally is that.) We would spending this money mainly on infrastructure and technology; we would be paying wages and creating millions of jobs.

So far as I know Sanders’s plan doesn’t include paying Brazil to restore the Amazon, but it probably should. Part of why Brazil is currently burning the Amazon is the externalities: The ecological benefit of the Amazon affects us all, but the economic benefit of clear-cutting and cattle ranching directly benefits Brazil. We should set up some sort of payment mechanism to ensure that it is more profitable for Brazil to keep the rainforest where it is than to burn it down. How can we afford such a thing, you ask? No: How can we afford not to?