Jun 24 JDN 2458294

By now you are probably aware of the fact that a new “zero tolerance” border security policy under the Trump administration has resulted in 2,000 children being forcibly separated from their parents by US government agents. If you weren’t, here are a variety of different sources all telling the same basic story of large-scale state violence and terror.

Make no mistake: This is an atrocity. The United Nations has explicitly condemned this human rights violation—to which Trump responded by making an unprecedented threat of withdrawing unilaterally from the UN Human Rights Council.

#ThisIsNotNormal, and Trump was everything we feared—everything we warned—he would be: Corrupt, incompetent, cruel, and authoritarian.

Yet Trump’s border policy differs mainly in degree, not kind, from existing US border policy. There is much more continuity here than most of us would like to admit.

The Trump administration has dramatically increased “interior removals”, the most obviously cruel acts, where ICE agents break into the houses of people living in the US and take them away. Don’t let the cold language fool you; this is literally people with guns breaking into your home and kidnapping members of your family. This is characteristic of totalitarian governments, not liberal democracies.

And yet, the Obama administration actually holds the record for most deportations (though only because they included “at-border deportations” which other administrations did not). A major policy change by George W. Bush started this whole process of detaining people at the border instead of releasing them and requiring them to return for later court dates.

I could keep going back; US border enforcement has gotten more and more aggressive as time goes on. US border security staffing has quintupled since just 1990. There was a time when the United States was a land of opportunity that welcomed “your tired, your poor, your huddled masses”; but that time is long past.

And this, in itself, is a human rights violation. Indeed, I am convinced that border security itself is inherently a human rights violation, always and everywhere; future generations will not praise us for being more restrained than Trump’s abject and intentional cruelty, but condemn us for acting under the same basic moral framework that justified it.

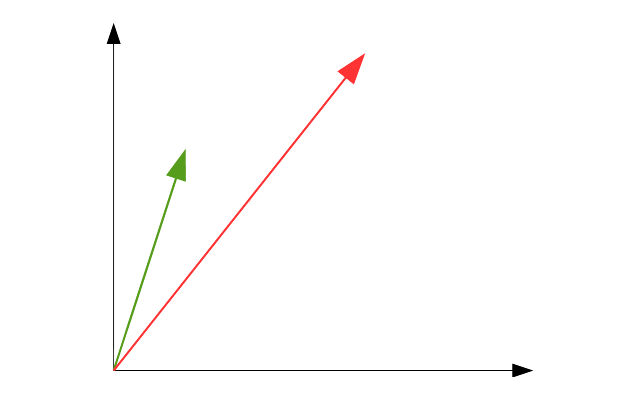

There is an imaginary line in the sand just a hundred miles south of where I sit now. On one side of the line, a typical family makes $66,000 per year. On the other side, a typical family makes only $20,000. On one side of the line, life expectancy is 81 years; on the other, 77. This means that over their lifetime, someone on this side of the line can expect to make over one million dollars more than they would if they had lived on the other side. Step across this line, get a million dollars; it sounds ridiculous, but it’s an empirical fact.

This would be bizarre enough by itself; but now consider that on that line there are fences, guard towers, and soldiers who will keep you from crossing it. If you have appropriate papers, you can cross; but if you don’t, they will arrest and detain you, potentially for months. This is not how we treat you if you are carrying contraband or have a criminal record. This is how we treat you if you don’t have a passport.

How can we possibly reconcile this with the principles of liberal democracy? Philosophers have tried, to be sure. Yet they invariably rely upon some notion that the people who want to cross our border are coming from another country where they were already granted basic human rights and democratic representation—which is almost never the case. People who come here from the UK or the Netherlands or generally have the proper visas. Even people who come here from China usually have visas—though China is by no means a liberal democracy. It’s people who come here from Haiti and Nicaragua who don’t—and these are some of the most corrupt and impoverished nations in the world.

As I said in an earlier post, I was not offended that Trump characterized countries like Haiti and Syria as “shitholes”. By any objective standard, that is accurate; these countries are terrible, terrible places to live. No, what offends me is that he thinks this gives us a right to turn these people away, as though the horrible conditions of their country somehow “rub off” on them and make them less worthy as human beings. On the contrary, we have a word for people who come from “shithole” countries seeking help, and that word is “refugee”.

Under international law, “refugee” has a very specific legal meaning, under which most immigrants do not qualify. But in a broader moral sense, almost every immigrant is a refugee. People don’t uproot themselves and travel thousands of miles on a whim. They are coming here because conditions in their home country are so bad that they simply cannot tolerate them anymore, and they come to us desperately seeking our help. They aren’t asking for handouts of free money—illegal immigrants are a net gain for our fiscal system, paying more in taxes than they receive in benefits. They are looking for jobs, and willing to accept much lower wages than the workers already here—because those wages are still dramatically higher than what they had where they came from.

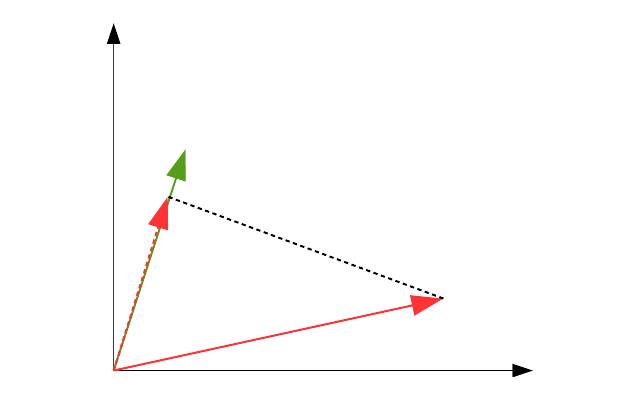

Of course, that does potentially mean they are competing with local low-wage workers, doesn’t it? Yes—but not as much as you might think. There is only a very weak relationship between higher immigration and lower wages (some studies find none at all!), even at the largest plausible estimates, the gain in welfare for the immigrants is dramatically higher than the loss in welfare for the low-wage workers who are already here. It’s not even a question of valuing them equally; as long as you value an immigrant at least one tenth as much as a native-born citizen, the equation comes out favoring more immigration.

This is for two reasons: One, most native-born workers already are unwilling to do the jobs that most immigrants do, such as picking fruit and laying masonry; and two, increased spending by immigrants boosts the local economy enough to compensate for any job losses.

But even aside from the economic impacts, what is the moral case for border security?

I have heard many people argue that “It’s our home, we should be able to decide who lives here.” First of all, there are some major differences between letting someone live in your home and letting someone come into your country. I’m not saying we should allow immigrants to force themselves into people’s homes, only that we shouldn’t arrest them when they try cross the border.

But even if I were to accept the analogy, if someone were fleeing oppression by an authoritarian government and asked to live in my home, I would let them. I would help hide them from the government if they were trying to escape persecution. I would even be willing to house people simply trying to escape poverty, as long as it were part of a well-organized program designed to ensure that everyone actually gets helped and the burden on homeowners and renters was not too great. I wouldn’t simply let homeless people come live here, because that creates all sorts of coordination problems (I can only fit so many, and how do I prioritize which ones?); but I’d absolutely participate in a program that coordinates placement of homeless families in apartments provided by volunteers. (In fact, maybe I should try to petition for such a program, as Southern California has a huge homelessness rate due to our ridiculous housing prices.)

Many people seem to fear that immigrants will bring crime, but actually they reduce crime rates. It’s really kind of astonishing how much less crime immigrants commit than locals. My hypothesis is that immigrants are a self-selected sample; the kind of person willing to move thousands of miles isn’t the kind of person who commits a lot of crimes.

I understand wanting to keep out terrorists and drug smugglers, but there are already plenty of terrorists and drug smugglers here in the US; if we are unwilling to set up border security between California and Nevada, I don’t see why we should be setting it up between California and Baja California. But okay, fine, we can keep the customs agents who inspect your belongings when you cross the border. If someone doesn’t have proper documentation, we can even detain and interrogate them—for a few hours, not a few months. The goal should be to detect dangerous criminals and nothing else. Once we are confident that you have not committed any felonies, we should let you through—frankly, we should give you a green card. We should only be willing to detain someone at the border for the same reasons we would be willing to detain a citizen who already lives here—that is, probable cause for an actual crime. (And no, you don’t get to count “illegal border crossing” as a crime, because that’s begging the question. By the same logic I could justify detaining people for jaywalking.)

A lot of people argue that restricting immigration is necessary to “preserve local culture”; but I’m not even sure that this is a goal sufficiently important to justify arresting and detaining people, and in any case, that’s really not how culture works. Culture is not advanced by purism and stagnation, but by openness and cross-pollination. From anime to pizza, many of our most valued cultural traditions would not exist without interaction across cultural boundaries. Introducing more Spanish speakers into the US may make us start saying no problemo and vamonos, but it’s not going to destroy liberal democracy. If you value culture, you should value interactions across different societies.

Most importantly, think about what you are trying to justify. Even if we stop doing Trump’s most extreme acts of cruelty, we are still talking about using military force to stop people from crossing an imaginary line. ICE basically treats people the same way the SS did. “Papers, please” isn’t something we associate with free societies—it’s characteristic of totalitarianism. We are so accustomed to border security (or so ignorant of its details) that we don’t see it for the atrocity it so obviously is.

National borders function something very much like feudal privilege. We have our “birthright”, which grants us all sorts of benefits and special privileges—literally tripling our incomes and extending our lives. We did nothing to earn this privilege. If anything, we show ourselves to be less deserving (e.g. by committing more crimes). And we use the government to defend our privilege by force.

Are people born on the other side of the line less human? Are they less morally worthy? On what grounds do we point guns at them and lock them away for the “crime” of wanting to live here?

What Trump is doing right now is horrific. But it is not that much more horrific than what we were already doing. My hope is that this will finally open our eyes to the horrors that we had been participating in all along.