Oct 8, JDN 2457670

Eleizer Yudkowsky (founder of the excellent blog forum Less Wrong) has a term he likes to use to distinguish his economic policy views from either liberal, conservative, or even libertarian: “econoliterate”, meaning the sort of economic policy ideas one comes up with when one actually knows a good deal about economics.

In general I think Yudkowsky overestimates this effect; I’ve known some very knowledgeable economists who disagree quite strongly over economic policy, and often following the conventional political lines of liberal versus conservative: Liberal economists want more progressive taxation and more Keynesian monetary and fiscal policy, while conservative economists want to reduce taxes on capital and remove regulations. Theoretically you can want all these things—as Miles Kimball does—but it’s rare. Conservative economists hate minimum wage, and lean on the theory that says it should be harmful to employment; liberal economists are ambivalent about minimum wage, and lean on the empirical data that shows it has almost no effect on employment. Which is more reliable? The empirical data, obviously—and until more economists start thinking that way, economics is never truly going to be a science as it should be.

But there are a few issues where Yudkowsky’s “econoliterate” concept really does seem to make sense, where there is one view held by most people, and another held by economists, regardless of who is liberal or conservative. One such example is free trade, which almost all economists believe in. A recent poll of prominent economists by the University of Chicago found literally zero who agreed with protectionist tariffs.

Another example is my topic for today: People losing their jobs.

Not unemployment, which both economists and almost everyone else agree is bad; but people losing their jobs. The general consensus among the public seems to be that people losing jobs is always bad, while economists generally consider it a sign of an economy that is run smoothly and efficiently.

To be clear, of course losing your job is bad for you; I don’t mean to imply that if you lose your job you shouldn’t be sad or frustrated or anxious about that, particularly not in our current system. Rather, I mean to say that policy which tries to keep people in their jobs is almost always a bad idea.

I think the problem is that most people don’t quite grasp that losing your job and not having a job are not the same thing. People not having jobs who want to have jobs—unemployment—is a bad thing. But losing your job doesn’t mean you have to stay unemployed; it could simply mean you get a new job. And indeed, that is what it should mean, if the economy is running properly.

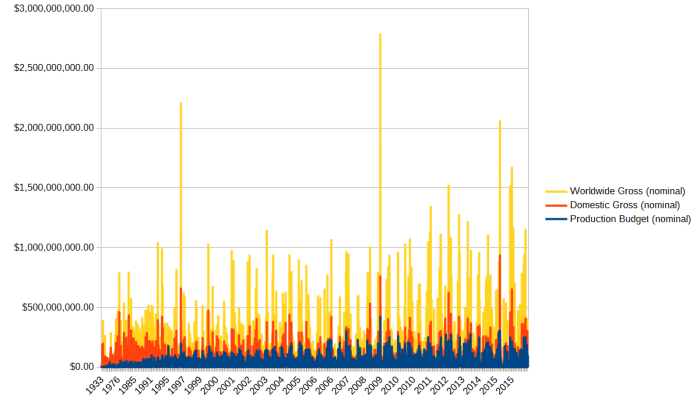

Check out this graph, from FRED:

The red line shows hires—people getting jobs. The blue line shows separations—people losing jobs or leaving jobs. During a recession (the most recent two are shown on this graph), people don’t actually leave their jobs faster than usual; if anything, slightly less. Instead what happens is that hiring rates drop dramatically. When the economy is doing well (as it is right now, more or less), both hires and separations are at very high rates.

Why is this? Well, think about what a job is, really: It’s something that needs done, that no one wants to do for free, so someone pays someone else to do it. Once that thing gets done, what should happen? The job should end. It’s done. The purpose of the job was not to provide for your standard of living; it was to achieve the task at hand. Once it doesn’t need done, why keep doing it?

We tend to lose sight of this, for a couple of reasons. First, we don’t have a basic income, and our social welfare system is very minimal; so a job usually is the only way people have to provide for their standard of living, and they come to think of this as the purpose of the job. Second, many jobs don’t really “get done” in any clear sense; individual tasks are completed, but new ones always arise. After every email sent is another received; after every patient treated is another who falls ill.

But even that is really only true in the short run. In the long run, almost all jobs do actually get done, in the sense that no one has to do them anymore. The job of cleaning up after horses is done (with rare exceptions). The job of manufacturing vacuum tubes for computers is done. Indeed, the job of being a computer—that used to be a profession, young women toiling away with slide rules—is very much done. There are no court jesters anymore, no town criers, and very few artisans (and even then, they’re really more like hobbyists). There are more writers now than ever, and occasional stenographers, but there are no scribes—no one powerful but illiterate pays others just to write things down, because no one powerful is illiterate (and even few who are not powerful, and fewer all the time).

When a job “gets done” in this long-run sense, we usually say that it is obsolete, and again think of this as somehow a bad thing, like we are somehow losing the ability to do something. No, we are gaining the ability to do something better. Jobs don’t become obsolete because we can’t do them anymore; they become obsolete because we don’t need to do them anymore. Instead of computers being a profession that toils with slide rules, they are thinking machines that fit in our pockets; and there are plenty of jobs now for software engineers, web developers, network administrators, hardware designers, and so on as a result.

Soon, there will be no coal miners, and very few oil drillers—or at least I hope so, for the sake of our planet’s climate. There will be far fewer auto workers (robots have already done most of that already), but far more construction workers who install rail lines. There will be more nuclear engineers, more photovoltaic researchers, even more miners and roofers, because we need to mine uranium and install solar panels on rooftops.

Yet even by saying that I am falling into the trap: I am making it sound like the benefit of new technology is that it opens up more new jobs. Typically it does do that, but that isn’t what it’s for. The purpose of technology is to get things done.

Remember my parable of the dishwasher. The goal of our economy is not to make people work; it is to provide people with goods and services. If we could invent a machine today that would do the job of everyone in the world and thereby put us all out of work, most people think that would be terrible—but in fact it would be wonderful.

Or at least it could be, if we did it right. See, the problem right now is that while poor people think that the purpose of a job is to provide for their needs, rich people think that the purpose of poor people is to do jobs. If there are no jobs to be done, why bother with them? At that point, they’re just in the way! (Think I’m exaggerating? Why else would anyone put a work requirement on TANF and SNAP? To do that, you must literally think that poor people do not deserve to eat or have homes if they aren’t, right now, working for an employer. You can couch that in cold economic jargon as “maximizing work incentives”, but that’s what you’re doing—you’re threatening people with starvation if they can’t or won’t find jobs.)

What would happen if we tried to stop people from losing their jobs? Typically, inefficiency. When you aren’t allowed to lay people off when they are no longer doing useful work, we end up in a situation where a large segment of the population is being paid but isn’t doing useful work—and unlike the situation with a basic income, those people would lose their income, at least temporarily, if they quit and tried to do something more useful. There is still considerable uncertainty within the empirical literature on just how much “employment protection” (laws that make it hard to lay people off) actually creates inefficiency and reduces productivity and employment, so it could be that this effect is small—but even so, likewise it does not seem to have the desired effect of reducing unemployment either. It may be like minimum wage, where the effect just isn’t all that large. But it’s probably not saving people from being unemployed; it may simply be shifting the distribution of unemployment so that people with protected jobs are almost never unemployed and people without it are unemployed much more frequently. (This doesn’t have to be based in law, either; while it is made by custom rather than law, it’s quite clear that tenure for university professors makes tenured professors vastly more secure, but at the cost of making employment tenuous and underpaid for adjuncts.)

There are other policies we could make that are better than employment protection, active labor market policies like those in Denmark that would make it easier to find a good job. Yet even then, we’re assuming that everyone needs jobs–and increasingly, that just isn’t true.

So, when we invent a new technology that replaces workers, workers are laid off from their jobs—and that is as it should be. What happens next is what we do wrong, and it’s not even anybody in particular; this is something our whole society does wrong: All those displaced workers get nothing. The extra profit from the more efficient production goes entirely to the shareholders of the corporation—and those shareholders are almost entirely members of the top 0.01%. So the poor get poorer and the rich get richer.

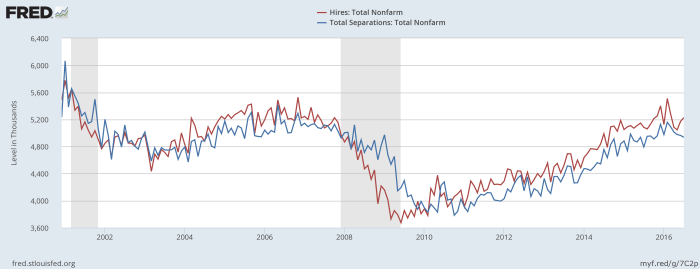

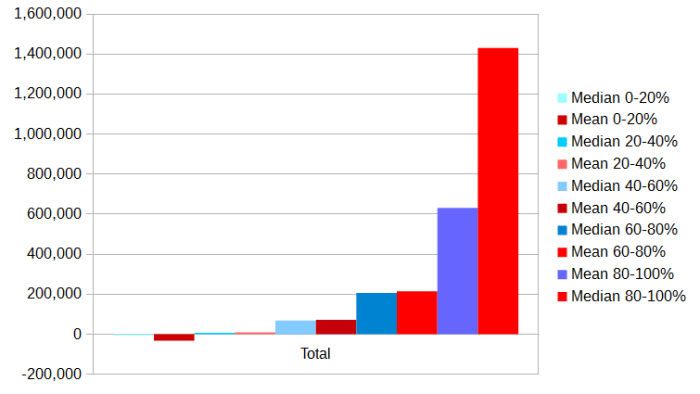

The real problem here is not that people lose their jobs; it’s that capital ownership is distributed so unequally. And boy, is it ever! Here are some graphs I made of the distribution of net wealth in the US, using from the US Census.

Here are the quintiles of the population as a whole:

And here are the medians by race:

Medians by age:

Medians by education:

And, perhaps most instructively, here are the quintiles of people who own their homes versus renting (The rent is too damn high!)

All that is just within the US, and already they are ranging from the mean net wealth of the lowest quintile of people under 35 (-$45,000, yes negative—student loans) to the mean net wealth of the highest quintile of people with graduate degrees ($3.8 million). All but the top quintile of renters are poorer than all but the bottom quintile of homeowners. And the median Black or Hispanic person has less than one-tenth the wealth of the median White or Asian person.

If we look worldwide, wealth inequality is even starker. Based on UN University figures, 40% of world wealth is owned by the top 1%; 70% by the top 5%; and 80% by the top 10%. There is less total wealth in the bottom 80% than in the 80-90% decile alone. According to Oxfam, the richest 85 individuals own as much net wealth as the poorest 3.7 billion. They are the 0.000,001%.

If we had an equal distribution of capital ownership, people would be happy when their jobs became obsolete, because it would free them up to do other things (either new jobs, or simply leisure time), while not decreasing their income—because they would be the shareholders receiving those extra profits from higher efficiency. People would be excited to hear about new technologies that might displace their work, especially if those technologies would displace the tedious and difficult parts and leave the creative and fun parts. Losing your job could be the best thing that ever happened to you.

The business cycle would still be a problem; we have good reason not to let recessions happen. But stopping the churn of hiring and firing wouldn’t actually make our society better off; it would keep people in jobs where they don’t belong and prevent us from using our time and labor for its best use.

Perhaps the reason most people don’t even think of this solution is precisely because of the extreme inequality of capital distribution—and the fact that it has more or less always been this way since the dawn of civilization. It doesn’t seem to even occur to most people that capital income is a thing that exists, because they are so far removed from actually having any amount of capital sufficient to generate meaningful income. Perhaps when a robot takes their job, on some level they imagine that the robot is getting paid, when of course it’s the shareholders of the corporations that made the robot and the corporations that are using the robot in place of workers. Or perhaps they imagine that those shareholders actually did so much hard work they deserve to get paid that money for all the hours they spent.

Because pay is for work, isn’t it? The reason you get money is because you’ve earned it by your hard work?

No. This is a lie, told to you by the rich and powerful in order to control you. They know full well that income doesn’t just come from wages—most of their income doesn’t come from wages! Yet this is even built into our language; we say “net worth” and “earnings” rather than “net wealth” and “income”. (Parade magazine has a regular segment called “What People Earn”; it should be called “What People Receive”.) Money is not your just reward for your hard work—at least, not always.

The reason you get money is that this is a useful means of allocating resources in our society. (Remember, money was created by governments for the purpose of facilitating economic transactions. It is not something that occurs in nature.) Wages are one way to do that, but they are far from the only way; they are not even the only way currently in use. As technology advances, we should expect a larger proportion of our income to go to capital—but what we’ve been doing wrong is setting it up so that only a handful of people actually own any capital.

Fix that, and maybe people will finally be able to see that losing your job isn’t such a bad thing; it could even be satisfying, the fulfillment of finally getting something done.