JDN 2457461

Recently I think I figured out why so many middle-class White Americans express so much guilt about global injustice: A lot of people seem to think that we actually benefit from it. Thus, they feel caught between a rock and a hard place; conquering injustice would mean undermining their own already precarious standard of living, while leaving it in place is unconscionable.

The compromise, is apparently to feel really, really guilty about it, constantly tell people to “check their privilege” in this bizarre form of trendy autoflagellation, and then… never really get around to doing anything about the injustice.

(I guess that’s better than the conservative interpretation, which seems to be that since we benefit from this, we should keep doing it, and make sure we elect big, strong leaders who will make that happen.)

So let me tell you in no uncertain words: You do not benefit from this.

If anyone does—and as I’ll get to in a moment, that is not even necessarily true—then it is the billionaires who own the multinational corporations that orchestrate these abuses. Billionaires and billionaires only stand to gain from the exploitation of workers in the US, China, and everywhere else.

How do I know this with such certainty? Allow me to explain.

First of all, it is a common perception that prices of goods would be unattainably high if they were not produced on the backs of sweatshop workers. This perception is mistaken. The primary effect of the exploitation is simply to raise the profits of the corporation; there is a secondary effect of raising the price a moderate amount; and even this would be overwhelmed by the long-run dynamic effect of the increased consumer spending if workers were paid fairly.

Let’s take an iPad, for example. The price of iPads varies around the world in a combination of purchasing power parity and outright price discrimination; but the top model almost never sells for less than $500. The raw material expenditure involved in producing one is about $370—and the labor expenditure? Just $11. Not $110; $11. If it had been $110, the price could still be kept under $500 and turn a profit; it would simply be much smaller. That is, even if prices are really so elastic that Americans would refuse to buy an iPad at any more than $500 that would still mean Apple could still afford to raise the wages they pay (or rather, their subcontractors pay) workers by an order of magnitude. A worker who currently works 50 hours a week for $10 per day could now make $10 per hour. And the price would not have to change; Apple would simply lose profit, which is why they don’t do this. In the absence of pressure to the contrary, corporations will do whatever they can to maximize profits.

Now, in fact, the price probably would go up, because Apple fans are among the most inelastic technology consumers in the world. But suppose it went up to $600, which would mean a 1:1 absorption of these higher labor expenditures into price. Does that really sound like “Americans could never afford this”? A few people right on the edge might decide they couldn’t buy it at that price, but it wouldn’t be very many—indeed, like any well-managed monopoly, Apple knows to stop raising the price at the point where they start losing more revenue than they gain.

Similarly, half the price of an iPhone is pure profit for Apple, and only 2% goes into labor. Once again, wages could be raised by an order of magnitude and the price would not need to change.

Apple is a particularly obvious example, but it’s quite simple to see why exploitative labor cannot be the source of improved economic efficiency. Paying workers less does not make them do better work. Treating people more harshly does not improve their performance. Quite the opposite: People work much harder when they are treated well. In addition, at the levels of income we’re talking about, small improvements in wages would result in substantial improvements in worker health, further improving performance. Finally, substitution effect dominates income effect at low incomes. At very high incomes, income effect can dominate substitution effect, so higher wages might result in less work—but it is precisely when we’re talking about poor people that it makes the least sense to say they would work less if you paid them more and treated them better.

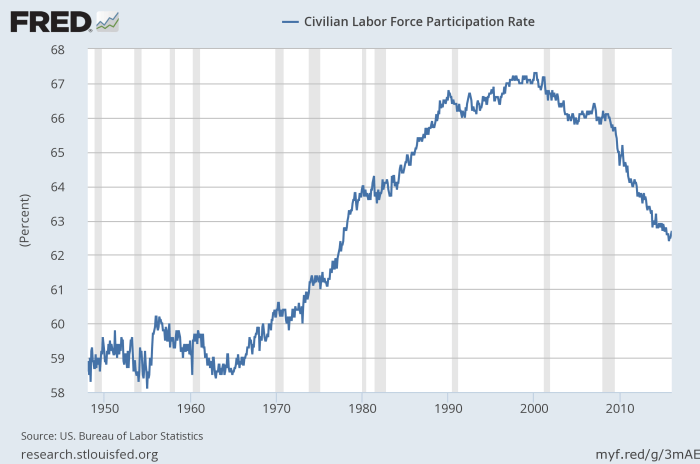

At most, paying higher wages can redistribute existing wealth, if we assume that the total amount of wealth does not increase. So it’s theoretically possible that paying higher wages to sweatshop workers would result in them getting some of the stuff that we currently have (essentially by a price mechanism where the things we want get more expensive, but our own wages don’t go up). But in fact our wages are most likely too low as well—wages in the US have become unlinked from productivity, around the time of Reagan—so there’s reason to think that a more just system would improve our standard of living also. Where would all the extra wealth come from? Well, there’s an awful lot of room at the top.

The top 1% in the US own 35% of net wealth, about as much as the bottom 95%. The 400 billionaires of the Forbes list have more wealth than the entire African-American population combined. (We’re double-counting Oprah—but that’s it, she’s the only African-American billionaire in the US.) So even assuming that the total amount of wealth remains constant (which is too conservative, as I’ll get to in a moment), improving global labor standards wouldn’t need to pull any wealth from the middle class; it could get plenty just from the top 0.01%.

In surveys, most Americans are willing to pay more for goods in order to improve labor standards—and the amounts that people are willing to pay, while they may seem small (on the order of 10% to 20% more), are in fact clearly enough that they could substantially increase the wages of sweatshop workers. The biggest problem is that corporations are so good at covering their tracks that it’s difficult to know whether you are really supporting higher labor standards. The multiple layers of international subcontractors make things even more complicated; the people who directly decide the wages are not the people who ultimately profit from them, because subcontractors are competitive while the multinationals that control them are monopsonists.

But for now I’m not going to deal with the thorny question of how we can actually regulate multinational corporations to stop them from using sweatshops. Right now, I just really want to get everyone on the same page and be absolutely clear about cui bono. If there is a benefit at all, it’s not going to you and me.

Why do I keep saying “if”? As so many people will ask me: “Isn’t it obvious that if one person gets less money, someone else must get more?” If you’ve been following my blog at all, you know that the answer is no.

On a single transaction, with everything else held constant, that is true. But we’re not talking about a single transaction. We’re talking about a system of global markets. Indeed, we’re not really talking about money at all; we’re talking about wealth.

By paying their workers so little that those workers can barely survive, corporations are making it impossible for those workers to go out and buy things of their own. Since the costs of higher wages are concentrated in one corporation while the benefits of higher wages are spread out across society, there is a Tragedy of the Commons where each corporation acting in its own self-interest undermines the consumer base that would have benefited all corporations (not to mention people who don’t own corporations). It does depend on some parameters we haven’t measured very precisely, but under a wide range of plausible values, it works out that literally everyone is worse off under this system than they would have been under a system of fair wages.

This is not simply theoretical. We have empirical data about what happened when companies (in the US at least) stopped using an even more extreme form of labor exploitation: slavery.

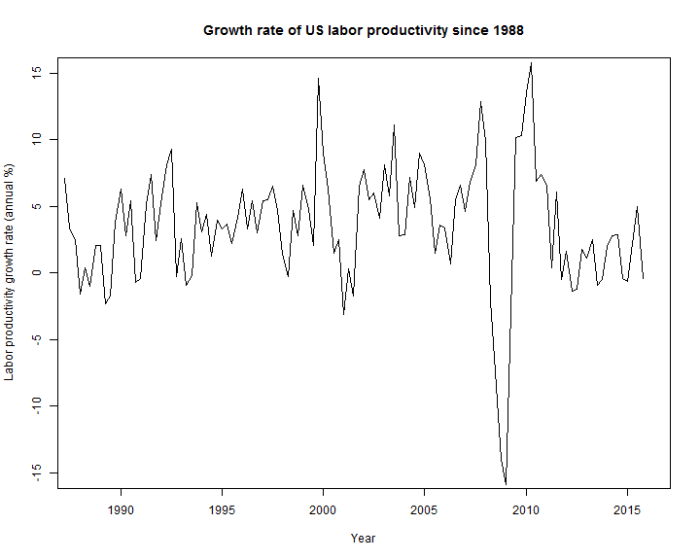

Because we were on the classical gold standard, GDP growth in the US in the 19th century was extremely erratic, jumping up and down as high as 10 lp and as low as -5 lp. But if you try to smooth out this roller-coaster business cycle, you can see that our growth rate did not appear tobe slowed by the ending of slavery:

Looking at the level of real per capita GDP (on a log scale) shows a continuous growth trend as if nothing had changed at all:

In fact, if you average the growth rates (in log points, averaging makes sense) from 1800 to 1860 as antebellum and from 1865 to 1900 as postbellum, you find that the antebellum growth rate averaged 1.04 lp, while the postbellum growth rate averaged 1.77 lp. Over a period of 50 years, that’s the difference between growing by a factor of 1.7 and growing by a factor of 2.4. Of course, there were a lot of other factors involved besides the end of slavery—but at the very least it seems clear that ending slavery did not reduce economic growth, which it would have if slavery were actually an efficient economic system.

This is a different question from whether slaveowners were irrational in continuing to own slaves. Purely on the basis of individual profit, it was most likely rational to own slaves. But the broader effects on the economic system as a whole were strongly negative. I think that part of why the debate on whether slavery is economically inefficient has never been settled is a confusion between these two questions. One side says “Slavery damaged overall economic growth.” The other says “But owning slaves produced a rate of return for investors as high as manufacturing!” Yeah, those… aren’t answering the same question. They are in fact probably both true. Something can be highly profitable for individuals while still being tremendously damaging to society.

I don’t mean to imply that sweatshops are as bad as slavery; they are not. (Though there is still slavery in the world, and some sweatshops tread a fine line.) What I’m saying is that showing that sweatshops are profitable (no doubt there) or even that they are better than most of the alternatives for their workers (probably true in most cases) does not show that they are economically efficient. Sweatshops are beneficent exploitation—they make workers better off, but in an obviously unjust way. And they only make workers better off compared to the current alternatives; if they were replaced with industries paying fair wages, workers would obviously be much better off still.

And my point is, so would we. While the prices of goods would increase slightly in the short run, in the long run the increased consumer spending by people in Third World countries—which soon would cease to be Third World countries, as happened in Korea and Japan—would result in additional trade with us that would raise our standard of living, not lower it. The only people it is even plausible to think would be harmed are the billionaires who own our multinational corporations; and yet even they might stand to benefit from the improved efficiency of the global economy.

No, you do not benefit from sweatshops. So stop feeling guilty, stop worrying so much about “checking your privilege”—and let’s get out there and do something about it.