Apr 16 JDN 2460049

The transition from neoclassical to behavioral economics has been a vital step forward in science. But lately we seem to have reached a plateau, with no major advances in the paradigm in quite some time.

It could be that there is work already being done which will, in hindsight, turn out to be significant enough to make that next step forward. But my fear is that we are getting bogged down by our own methodological limitations.

Neoclassical economics shared with us its obsession with mathematical sophistication. To some extent this was inevitable; in order to impress neoclassical economists enough to convert some of them, we had to use fancy math. We had to show that we could do it their way in order to convince them why we shouldn’t—otherwise, they’d just have dismissed us the way they had dismissed psychologists for decades, as too “fuzzy-headed” to do the “hard work” of putting everything into equations.

But the truth is, putting everything into equations was never the right approach. Because human beings clearly don’t think in equations. Once we write down a utility function and get ready to take its derivative and set it equal to zero, we have already distanced ourselves from how human thought actually works.

When dealing with a simple physical system, like an atom, equations make sense. Nobody thinks that the electron knows the equation and is following it intentionally. That equation simply describes how the forces of the universe operate, and the electron is subject to those forces.

But human beings do actually know things and do things intentionally. And while an equation could be useful for analyzing human behavior in the aggregate—I’m certainly not objecting to statistical analysis—it really never made sense to say that people make their decisions by optimizing the value of some function. Most people barely even know what a function is, much less remember calculus well enough to optimize one.

Yet right now, behavioral economics is still all based in that utility-maximization paradigm. We don’t use the same simplistic utility functions as neoclassical economists; we make them more sophisticated and realistic. Yet in that very sophistication we make things more complicated, more difficult—and thus in at least that respect, even further removed from how actual human thought must operate.

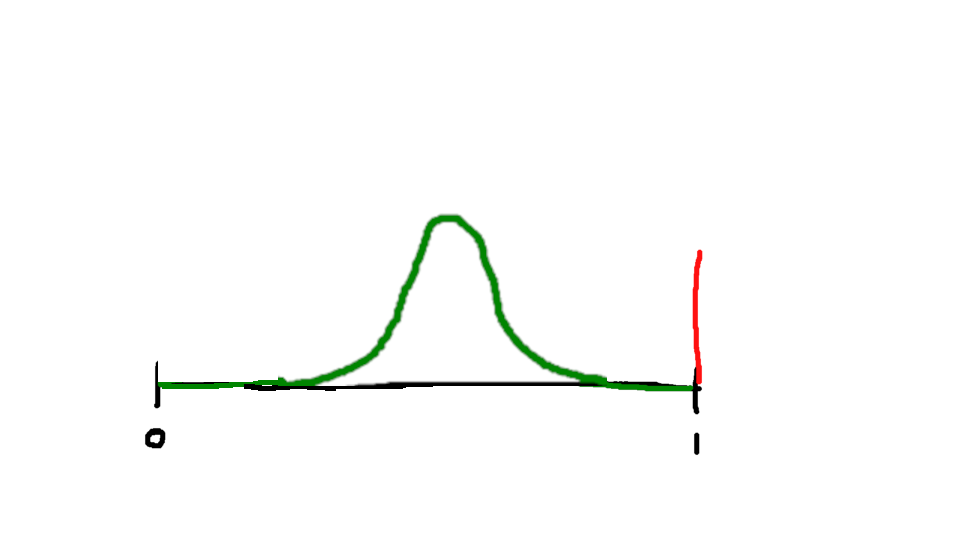

The worst offender here is surely Prospect Theory. I recognize that Prospect Theory predicts human behavior better than conventional expected utility theory; nevertheless, it makes absolutely no sense to suppose that human beings actually do some kind of probability-weighting calculation in their heads when they make judgments. Most of my students—who are well-trained in mathematics and economics—can’t even do that probability-weighting calculation on paper, with a calculator, on an exam. (There’s also absolutely no reason to do it! All it does it make your decisions worse!) This is a totally unrealistic model of human thought.

This is not to say that human beings are stupid. We are still smarter than any other entity in the known universe—computers are rapidly catching up, but they haven’t caught up yet. It is just that whatever makes us smart must not be easily expressible as an equation that maximizes a function. Our thoughts are bundles of heuristics, each of which may be individually quite simple, but all of which together make us capable of not only intelligence, but something computers still sorely, pathetically lack: wisdom. Computers optimize functions better than we ever will, but we still make better decisions than they do.

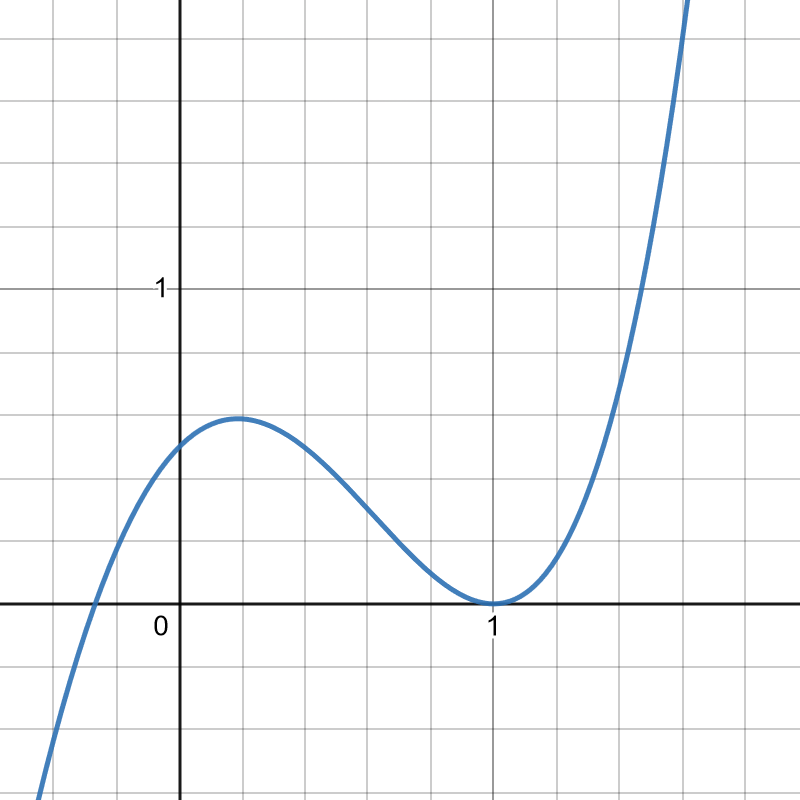

I think that what behavioral economics needs now is a new unifying theory of these heuristics, which accounts for not only how they work, but how we select which one to use in a given situation, and perhaps even where they come from in the first place. This new theory will of course be complex; there’s a lot of things to explain, and human behavior is a very complex phenomenon. But it shouldn’t be—mustn’t be—reliant on sophisticated advanced mathematics, because most people can’t do advanced mathematics (almost by construction—we would call it something different otherwise). If your model assumes that people are taking derivatives in their heads, your model is already broken. 90% of the world’s people can’t take a derivative.

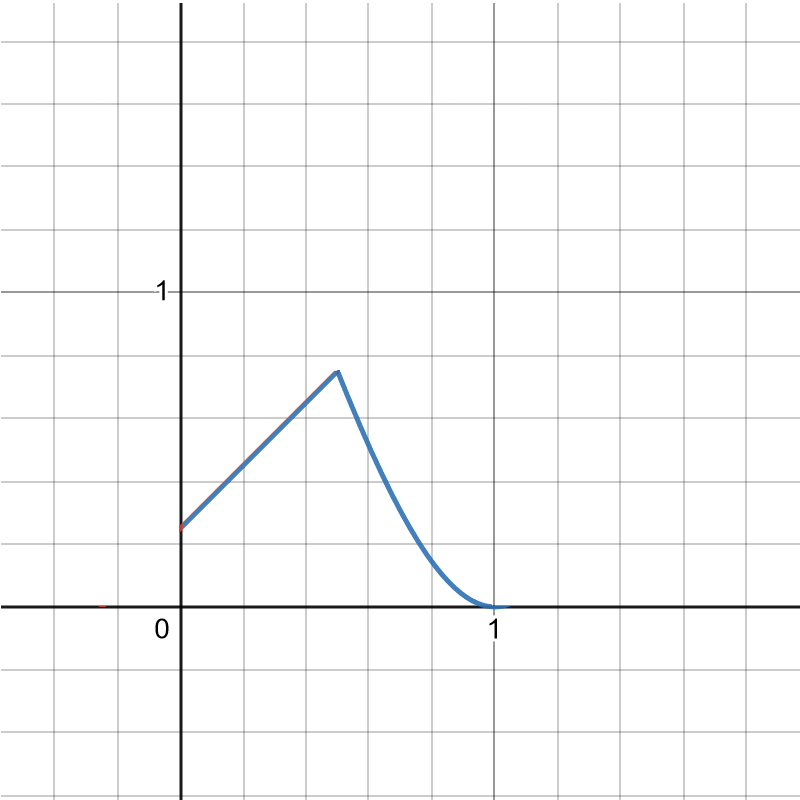

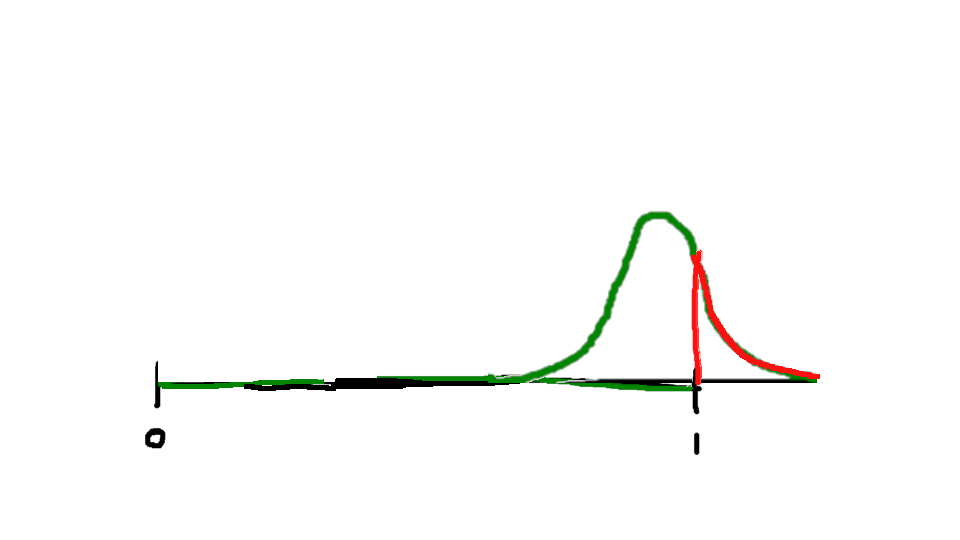

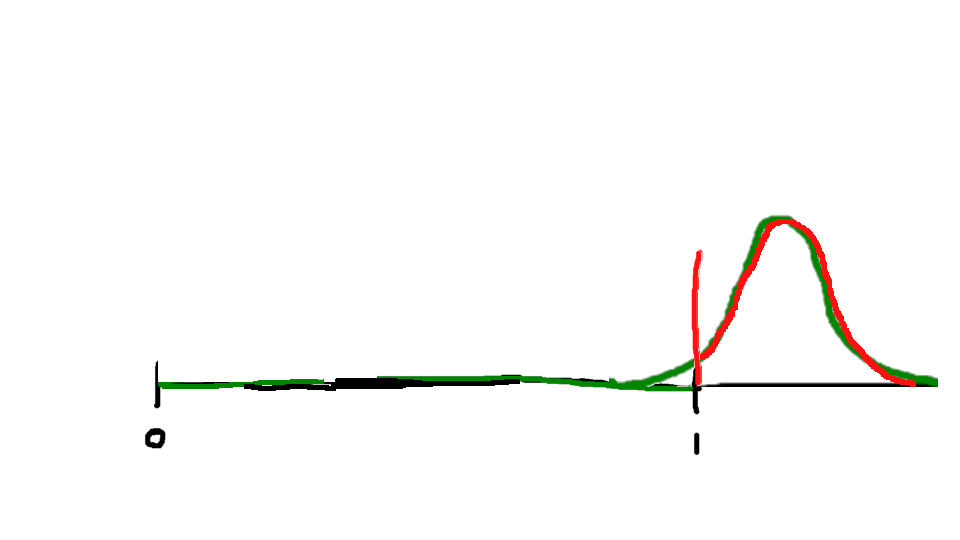

I guess it could be that our cognitive processes in some sense operate as if they are optimizing some function. This is commonly posited for the human motor system, for instance; clearly baseball players aren’t actually solving differential equations when they throw and catch balls, but the trajectories that balls follow do in fact obey such equations, and the reliability with which baseball players can catch and throw suggests that they are in some sense acting as if they can solve them.

But I think that a careful analysis of even this classic example reveals some deeper insights that should call this whole notion into question. How do baseball players actually do what they do? They don’t seem to be calculating at all—in fact, if you asked them to try to calculate while they were playing, it would destroy their ability to play. They learn. They engage in practiced motions, acquire skills, and notice patterns. I don’t think there is anywhere in their brains that is actually doing anything like solving a differential equation. It’s all a process of throwing and catching, throwing and catching, over and over again, watching and remembering and subtly adjusting.

One thing that is particularly interesting to me about that process is that is astonishingly flexible. It doesn’t really seem to matter what physical process you are interacting with; as long as it is sufficiently orderly, such a method will allow you to predict and ultimately control that process. You don’t need to know anything about differential equations in order to learn in this way—and, indeed, I really can’t emphasize this enough, baseball players typically don’t.

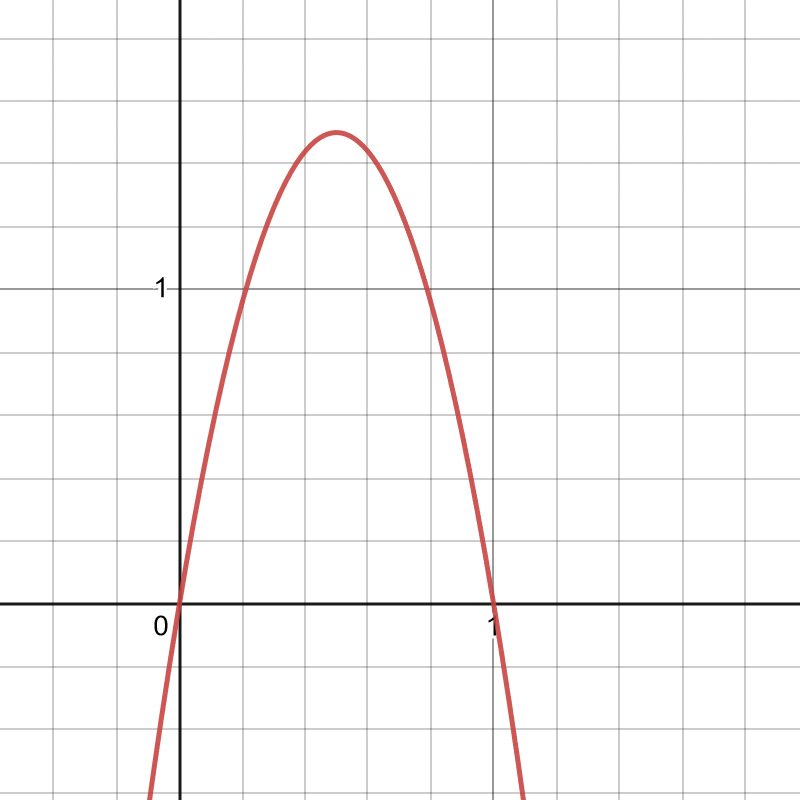

In fact, learning is so flexible that it can even perform better than calculation. The usual differential equations most people would think to use to predict the throw of a ball would assume ballistic motion in a vacuum, which absolutely not what a curveball is. In order to throw a curveball, the ball must interact with the air, and it must be launched with spin; curving a baseball relies very heavily on the Magnus Effect. I think it’s probably possible to construct an equation that would fully predict the motion of a curveball, but it would be a tremendously complicated one, and might not even have an exact closed-form solution. In fact, I think it would require solving the Navier-Stokes equations, for which there is an outstanding Millennium Prize. Since the viscosity of air is very low, maybe you could get away with approximating using the Euler fluid equations.

To be fair, a learning process that is adapting to a system that obeys an equation will yield results that become an ever-closer approximation of that equation. And it is in that sense that a baseball player can be said to be acting as if solving a differential equation. But this relies heavily on the system in question being one that obeys an equation—and when it comes to economic systems, is that even true?

What if the reason we can’t find a simple set of equations that accurately describe the economy (as opposed to equations of ever-escalating complexity that still utterly fail to describe the economy) is that there isn’t one? What if the reason we can’t find the utility function people are maximizing is that they aren’t maximizing anything?

What behavioral economics needs now is a new approach, something less constrained by the norms of neoclassical economics and more aligned with psychology and cognitive science. We should be modeling human beings based on how they actually think, not some weird mathematical construct that bears no resemblance to human reasoning but is designed to impress people who are obsessed with math.

I’m of course not the first person to have suggested this. I probably won’t be the last, or even the one who most gets listened to. But I hope that I might get at least a few more people to listen to it, because I have gone through the mathematical gauntlet and earned my bona fides. It is too easy to dismiss this kind of reasoning from people who don’t actually understand advanced mathematics. But I do understand differential equations—and I’m telling you, that’s not how people think.