July 9, JDN 2457944

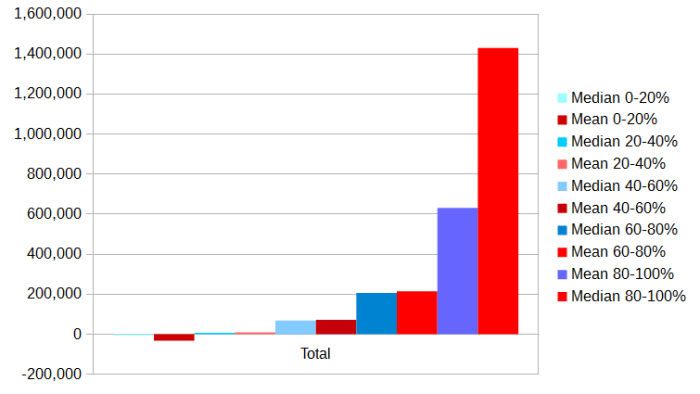

Most people don’t buy stocks at all. Stock equity is the quintessential form of financial wealth, and 42% of financial net wealth in the United States is held by the top 1%, while the bottom 80% owns essentially none.

Half of American households do not have any private retirement savings at all, and are depending either on employee pensions or Social Security for their retirement plans.

This is not necessarily irrational. In order to save for retirement, one must first have sufficient income to live on. Indeed, I got very annoyed at a “financial planning seminar” for grad students I attended recently, trying to scare us about the fact that almost none of us had any meaningful retirement savings. No, we shouldn’t have meaningful retirement savings, because our income is currently much lower than what we can expect to get once we graduate and enter our professions. It doesn’t make sense for someone scraping by on a $20,000 per year graduate student stipend to be saving up for retirement, when they can quite reasonably expect to be making $70,000-$100,000 per year once they finally get that PhD and become a professional economist (or sociologist, or psychologist or physicist or statistician or political scientist or material, mechanical, chemical, or aerospace engineer, or college professor in general, etc.). Even social workers, historians, and archaeologists make a lot more money than grad students. If you are already in the workforce and only expect to be getting small raises in the future, maybe you should start saving for retirement in your 20s. If you’re a grad student, don’t bother. It’ll be a lot easier to save once your income triples after graduation. (Personally, I keep about $700 in stocks mostly to get a feel for what it is like owning and trading stocks that I will apply later, not out of any serious expectation to support a retirement fund. Even at Warren Buffet-level returns I wouldn’t make more than $200 a year this way.)

Total US retirement savings are over $25 trillion, which… does actually sound low to me. In a country with a GDP now over $19 trillion, that means we’ve only saved a year and change of total income. If we had a rapidly growing population this might be fine, but we don’t; our population is fairly stable. People seem to be relying on economic growth to provide for their retirement, and since we are almost certainly at steady-state capital stock and fairly near full employment, that means waiting for technological advancement.

So basically people are hoping that we get to the Wall-E future where the robots will provide for us. And hey, maybe we will; but assuming that we haven’t abandoned capitalism by then (as they certainly haven’t in Wall-E), maybe you should try to make sure you own some assets to pay for robots with?

But okay, let’s set all that aside, and say you do actually want to save for retirement. How should you go about doing it?

Stocks are clearly the way to go. A certain proportion of government bonds also makes sense as a hedge against risk, and maybe you should even throw in the occasional commodity future. I wouldn’t recommend oil or coal at this point—either we do something about climate change and those prices plummet, or we don’t and we’ve got bigger problems—but it’s hard to go wrong with corn or steel, and for this one purpose it also can make sense to buy gold as well. Gold is not a magical panacea or the foundation of all wealth, but its price does tend to correlate negatively with stock returns, so it’s not a bad risk hedge.

Don’t buy exotic derivatives unless you really know what you’re doing—they can make a lot of money, but they can lose it just as fast—and never buy non-portfolio assets as a financial investment. If your goal is to buy something to make money, make it something you can trade at the click of a button. Buy a house because you want to live in that house. Buy wine because you like drinking wine. Don’t buy a house in the hopes of making a financial return—you’ll have leveraged your entire portfolio 10 to 1 while leaving it completely undiversified. And the problem with investing in wine, ironically, is its lack of liquidity.

The core of your investment portfolio should definitely be stocks. The biggest reason for this is the equity premium; equities—that is, stocks—get returns so much higher than other assets that it’s actually baffling to most economists. Bond returns are currently terrible, while stock returns are currently fantastic. The former is currently near 0% in inflation-adjusted terms, while the latter is closer to 16%. If this continues for the next 10 years, that means that $1000 put in bonds would be worth… $1000, while $1000 put in stocks would be worth $4400. So, do you want to keep the same amount of money, or quadruple your money? It’s up to you.

Higher risk is generally associated with higher return, because rational investors will only accept additional risk when they get some additional benefit from it; and stocks are indeed riskier than most other assets, but not that much riskier. For this to be rational, people would need to be extremely risk-averse, to the point where they should never drive a car or eat a cheeseburger. (Of course, human beings are terrible at assessing risk, so what I really think is going on is that people wildly underestimate the risk of driving a car and wildly overestimate the risk of buying stocks.)

Next, you may be asking: How does one buy stocks? This doesn’t seem to be something people teach in school.

You will need a brokerage of some sort. There are many such brokerages, but they are basically all equivalent except for the fees they charge. Some of them will try to offer you various bells and whistles to justify whatever additional cut they get of your trades, but they are almost never worth it. You should choose one that has a low a trade fee as possible, because even a few dollars here and there can add up surprisingly quickly.

Fortunately, there is now at least one well-established reliable stock brokerage available to almost anyone that has a standard trade fee of zero. They are called Robinhood, and I highly recommend them. If they have any downside, it is ironically that they make trading too easy, so you can be tempted to do it too often. Learn to resist that urge, and they will serve you well and cost you nothing.

Now, which stocks should you buy? There are a lot of them out there. The answer I’m going to give may sound strange: All of them. You should buy all the stocks.

All of them? How can you buy all of them? Wouldn’t that be ludicrously expensive?

No, it’s quite affordable in fact. In my little $700 portfolio, I own every single stock in the S&P 500 and the NASDAQ. If I get a little extra money to save, I may expand to own every stock in Europe and China as well.

How? A clever little arrangement called an exchange-traded fund, or ETF for short. An ETF is actually a form of mutual fund, where the fund purchases shares in a huge array of stocks, and adjusts what they own to precisely track the behavior of an entire stock market (such as the S&P 500). Then what you can buy is shares in that mutual fund, which are usually priced somewhere between $100 and $300 each. As the price of stocks in the market rises, the price of shares in the mutual fund rises to match, and you can reap the same capital gains they do.

A major advantage of this arrangement, especially for a typical person who isn’t well-versed in stock markets, is that it requires almost no attention at your end. You can buy into a few ETFs and then leave your money to sit there, knowing that it will grow as long as the overall stock market grows.

But there is an even more important advantage, which is that it maximizes your diversification. I said earlier that you shouldn’t buy a house as an investment, because it’s not at all diversified. What I mean by this is that the price of that house depends only on one thing—that house itself. If the price of that house changes, the full change is reflected immediately in the value of your asset. In fact, if you have 10% down on a mortgage, the full change is reflected ten times over in your net wealth, because you are leveraged 10 to 1.

An ETF is basically the opposite of that. Instead of its price depending on only one thing, it depends on a vast array of things, averaging over the prices of literally hundreds or thousands of different corporations. When some fall, others will rise. On average, as long as the economy continues to grow, they will rise.

The result is that you can get the same average return you would from owning stocks, while dramatically reducing the risk you bear.

To see how this works, consider the past year’s performance of Apple (AAPL), which has done very well, versus Fitbit (FIT), which has done very poorly, compared with the NASDAQ as a whole, of which they are both part.

AAPL has grown over 50% (40 log points) in the last year; so if you’d bought $1000 of their stock a year ago it would be worth $1500. FIT has fallen over 60% (84 log points) in the same time, so if you’d bought $1000 of their stock instead, it would be worth only $400. That’s the risk you’re taking by buying individual stocks.

Whereas, if you had simply bought a NASDAQ ETF a year ago, your return would be 35%, so that $1000 would be worth $1350.

Of course, that does mean you don’t get as high a return as you would if you had managed to choose the highest-performing stock on that index. But you’re unlikely to be able to do that, as even professional financial forecasters are worse than random chance. So, would you rather take a 50-50 shot between gaining $500 and losing $600, or would you prefer a guaranteed $350?

If higher return is not your only goal, and you want to be socially responsible in your investments, there are ETFs for that too. Instead of buying the whole stock market, these funds buy only a section of the market that is associated with some social benefit, such as lower carbon emissions or better representation of women in management. On average, you can expect a slightly lower return this way; but you are also helping to make a better world. And still your average return is generally going to be better than it would be if you tried to pick individual stocks yourself. In fact, certain classes of socially-responsible funds—particularly green tech and women’s representation—actually perform better than conventional ETFs, probably because most investors undervalue renewable energy and, well, also undervalue women. Women CEOs perform better at lower prices; why would you not want to buy their companies?

In fact ETFs are not literally guaranteed—the market as a whole does move up and down, so it is possible to lose money even by buying ETFs. But because the risk is so much lower, your odds of losing money are considerably reduced. And on average, an ETF will, by construction, perform exactly as well as the average performance of a randomly-chosen stock from that market.

Indeed, I am quite convinced that most people don’t take enough risk on their investment portfolios, because they confuse two very different types of risk.

The kind you should be worried about is idiosyncratic risk, which is risk tied to a particular investment—the risk of having chosen the Fitbit instead of Apple. But a lot of the time people seem to be avoiding market risk, which is the risk tied to changes in the market as a whole. Avoiding market risk does reduce your chances of losing money, but it does so at the cost of reducing your chances of making money even more.

Idiosyncratic risk is basically all downside. Yeah, you could get lucky; but you could just as well get unlucky. Far better if you could somehow average over that risk and get the average return. But with diversification, that is exactly what you can do. Then you are left only with market risk, which is the kind of risk that is directly tied to higher average returns.

Young people should especially be willing to take more risk in their portfolios. As you get closer to retirement, it becomes important to have more certainty about how much money will really be available to you once you retire. But if retirement is still 30 years away, the thing you should care most about is maximizing your average return. That means taking on a lot of market risk, which is then less risky overall if you diversify away the idiosyncratic risk.

I hope now that I have convinced you to avoid buying individual stocks. For most people most of the time, this is the advice you need to hear. Don’t try to forecast the market, don’t try to outperform the indexes; just buy and hold some ETFs and leave your money alone to grow.

But if you really must buy individual stocks, either because you think you are savvy enough to beat the forecasters or because you enjoy the gamble, here’s some additional advice I have for you.

My first piece of advice is that you should still buy ETFs. Even if you’re willing to risk some of your wealth on greater gambles, don’t risk all of it that way.

My second piece of advice is to buy primarily large, well-established companies (like Apple or Microsoft or Ford or General Electric). Their stocks certainly do rise and fall, but they are unlikely to completely crash and burn the way that young companies like Fitbit can.

My third piece of advice is to watch the price-earnings ratio (P/E for short). Roughly speaking, this is the number of years it would take for the profits of this corporation to pay off the value of its stock. If they pay most of their profits in dividends, it is approximately how many years you’d need to hold the stock in order to get as much in dividends as you paid for the shares.

Do you want P/E to be large or small? You want it to be small. This is called value investing, but it really should just be called “investing”. The alternatives to value investing are actually not investment but speculation and arbitrage. If you are actually investing, you are buying into companies that are currently undervalued; you want them to be cheap.

Of course, it is not always easy to tell whether a company is undervalued. A common rule-of-thumb is that you should aim for a P/E around 20 (20 years to pay off means about 5% return in dividends); if the P/E is below 10, it’s a fantastic deal, and if it is above 30, it might not be worth the price. But reality is of course more complicated than this. You don’t actually care about current earnings, you care about future earnings, and it could be that a company which is earning very little now will earn more later, or vice-versa. The more you can learn about a company, the better judgment you can make about their future profitability; this is another reason why it makes sense to buy large, well-known companies rather than tiny startups.

My final piece of advice is not to trade too frequently. Especially with something like Robinhood where trades are instant and free, it can be tempting to try to ride every little ripple in the market. Up 0.5%? Sell! Down 0.3%? Buy! And yes, in principle, if you could perfectly forecast every such fluctuation, this would be optimal—and make you an almost obscene amount of money. But you can’t. We know you can’t. You need to remember that you can’t. You should only trade if one of two things happens: Either your situation changes, or the company’s situation changes. If you need the money, sell, to get the money. If you have extra savings, buy, to give those savings a good return. If something bad happened to the company and their profits are going to fall, sell. If something good happened to the company and their profits are going to rise, buy. Otherwise, hold. In the long run, those who hold stocks longer are better off.