JDN 2457433

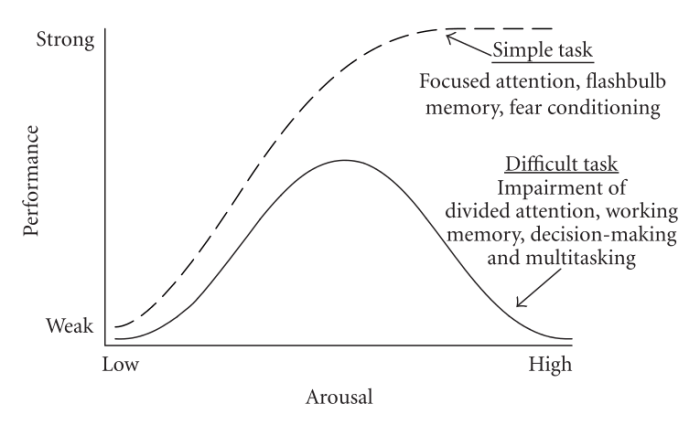

One of the more surprising findings from the study of human behavior under stress is the Yerkes-Dodson curve:

This curve shows how well humans perform at a given task, as a function of how high the stakes are on whether or not they do it properly.

For simple tasks, it says what most people intuitively expect—and what neoclassical economists appear to believe: As the stakes rise, the more highly incentivized you are to do it, and the better you do it.

But for complex tasks, it says something quite different: While increased stakes do raise performance to a point—with nothing at stake at all, people hardly work at all—it is possible to become too incentivized. Formally we say the curve is not monotonic; it has a local maximum.

This is one of many reasons why it’s ridiculous to say that top CEOs should make tens of millions of dollars a year on the rise and fall of their company’s stock price (as a great many economists do in fact say). Even if I believed that stock prices accurately reflect the company’s viability (they do not), and believed that the CEO has a great deal to do with the company’s success, it would still be a case of overincentivizing. When a million dollars rides on a decision, that decision is going to be worse than if the stakes had only been $100. With this in mind, it’s really not surprising that higher CEO pay is correlated with worse company performance. Stock options are terrible motivators, but do offer a subtle way of making wages adjust to the business cycle.

The reason for this is that as the stakes get higher, we become stressed, and that stress response inhibits our ability to use higher cognitive functions. The sympathetic nervous system evolved to make us very good at fighting or running away in the face of danger, which works well should you ever be attacked by a tiger. It did not evolve to make us good at complex tasks under high stakes, the sort of skill we’d need when calculating the trajectory of an errant spacecraft or disarming a nuclear warhead.

To be fair, most of us never have to worry about piloting errant spacecraft or disarming nuclear warheads—indeed, you’re about as likely to get attacked by a tiger even in today’s world. (The rate of tiger attacks in the US is just under 2 per year, and the rate of manned space launches in the US was about 5 per year until the Space Shuttle was terminated.)

There are certain professions, such as pilots and surgeons, where performing complex tasks under life-or-death pressure is commonplace, but only a small fraction of people take such professions for precisely that reason. And if you’ve ever wondered why we use checklists for pilots and there is discussion of also using checklists for surgeons, this is why—checklists convert a single complex task into many simple tasks, allowing high performance even at extreme stakes.

But we do have to do a fair number of quite complex tasks with stakes that are, if not urgent life-or-death scenarios, then at least actions that affect our long-term life prospects substantially. In my tutoring business I encounter one in particular quite frequently: Standardized tests.

Tests like the SAT, ACT, GRE, LSAT, GMAT, and other assorted acronyms are not literally life-or-death, but they often feel that way to students because they really do have a powerful impact on where you’ll end up in life. Will you get into a good college? Will you get into grad school? Will you get the job you want? Even subtle deviations from the path of optimal academic success can make it much harder to achieve career success in the future.

Of course, these are hardly the only examples. Many jobs require us to complete tasks properly on tight deadlines, or else risk being fired. Working in academia infamously requires publishing in journals in time to rise up the tenure track, or else falling off the track entirely. (This incentivizes the production of huge numbers of papers, whether they’re worth writing or not; yes, the number of papers published goes down after tenure, but is that a bad thing? What we need to know is whether the number of good papers goes down. My suspicion is that most if not all of the reduction in publications is due to not publishing things that weren’t worth publishing.)

So if you are faced with this sort of task, what can you do? If you realize that you are faced with a high-stakes complex task, you know your performance will be bad—which only makes your stress worse!

My advice is to pretend you’re betting five dollars on the outcome.

Ignore all other stakes, and pretend you’re betting five dollars. $5.00 USD. Do it right and you get a Lincoln; do it wrong and you lose one.

What this does is ensures that you care enough—you don’t want to lose $5 for no reason—but not too much—if you do lose $5, you don’t feel like your life is ending. We want to put you near that peak of the Yerkes-Dodson curve.

The great irony here is that you most want to do this when it is most untrue. If you actually do have a task for which you’ve bet $5 and nothing else rides on it, you don’t need this technique, and any technique to improve your performance is not particularly worthwhile. It’s when you have a standardized test to pass that you really want to use this—and part of me even hopes that people know to do this whenever they have nuclear warheads to disarm. It is precisely when the stakes are highest that you must put those stakes out of your mind.

Why five dollars? Well, the exact amount is arbitrary, but this is at least about the right order of magnitude for most First World individuals. If you really want to get precise, I think the optimal stakes level for maximum performance is something like 100 microQALY per task, and assuming logarithmic utility of wealth, $5 at the US median household income of $53,600 is approximately 100 microQALY. If you have a particularly low or high income, feel free to adjust accordingly. Literally you should be prepared to bet about an hour of your life; but we are not accustomed to thinking that way, so use $5. (I think most people, if asked outright, would radically overestimate what an hour of life is worth to them. “I wouldn’t give up an hour of my life for $1,000!” Then why do you work at $20 an hour?)

It’s a simple heuristic, easy to remember, and sometimes effective. Give it a try.