JDN 2457569

This post is going to be a little wonkier than most; I’m actually trying to sort out my thoughts and draw some public comment on a theory that has been dancing around my head for awhile. The original idea of separating terms in marginal utility of wealth was actually suggested by my boyfriend, and from there I’ve been trying to give it some more mathematical precision to see if I can come up with a way to test it experimentally. My thinking is also influenced by a paper Miles Kimball wrote about the distinction between happiness and utility.

There are lots of ways one could conceivably spend money—everything from watching football games to buying refrigerators to building museums to inventing vaccines. But insofar as we are rational (and we are after all about 90% rational), we’re going to try to spend our money in such a way that its marginal utility is approximately equal across various activities. You’ll buy one refrigerator, maybe two, but not seven, because the marginal utility of refrigerators drops off pretty fast; instead you’ll spend that money elsewhere. You probably won’t buy a house that’s twice as large if it means you can’t afford groceries anymore. I don’t think our spending is truly optimal at maximizing utility, but I think it’s fairly good.

Therefore, it doesn’t make much sense to break down marginal utility of wealth into all these different categories—cars, refrigerators, football games, shoes, and so on—because we already do a fairly good job of equalizing marginal utility across all those different categories. I could see breaking it down into a few specific categories, such as food, housing, transportation, medicine, and entertainment (and this definitely seems useful for making your own household budget); but even then, I don’t get the impression that most people routinely spend too much on one of these categories and not enough on the others.

However, I can think of two quite different fundamental motives behind spending money, which I think are distinct enough to be worth separating.

One way to spend money is on yourself, raising your own standard of living, making yourself more comfortable. This would include both football games and refrigerators, really anything that makes your life better. We could call this the consumption motive, or maybe simply the self-directed motive.

The other way is to spend it on other people, which, depending on your personality can take either the form of philanthropy to help others, or as a means of self-aggrandizement to raise your own relative status. It’s also possible to do both at the same time in various combinations; while the Gates Foundation is almost entirely philanthropic and Trump Tower is almost entirely self-aggrandizing, Carnegie Hall falls somewhere in between, being at once a significant contribution to our society and an obvious attempt to bring praise and adulation to himself. I would also include spending on Veblen goods that are mainly to show off your own wealth and status in this category. We can call this spending the philanthropic/status motive, or simply the other-directed motive.

There is some spending which combines both motives: A car is surely useful, but a Ferrari is mainly for show—but then, a Lexus or a BMW could be either to show off or really because you like the car better. Some form of housing is a basic human need, and bigger, fancier houses are often better, but the main reason one builds mansions in Beverly Hills is to demonstrate to the world that one is fabulously rich. This complicates the theory somewhat, but basically I think the best approach is to try to separate a sort of “spending proportion” on such goods, so that say $20,000 of the Lexus is for usefulness and $15,000 is for show. Empirically this might be hard to do, but theoretically it makes sense.

One of the central mysteries in cognitive economics right now is the fact that while self-reported happiness rises very little, if at all, as income increases, a finding which was recently replicated even in poor countries where we might not expect it to be true, nonetheless self-reported satisfaction continues to rise indefinitely. A number of theories have been proposed to explain this apparent paradox.

This model might just be able to account for that, if by “happiness” we’re really talking about the self-directed motive, and by “satisfaction” we’re talking about the other-directed motive. Self-reported happiness seems to obey a rule that $100 is worth as much to someone with $10,000 as $25 is to someone with $5,000, or $400 to someone with $20,000.

Self-reported satisfaction seems to obey a different rule, such that each unit of additional satisfaction requires a roughly equal proportional increase in income.

By having a utility function with two terms, we can account for both of these effects. Total utility will be u(x), happiness h(x), and satisfaction s(x).

u(x) = h(x) + s(x)

To obey the above rule, happiness must obey harmonic utility, like this, for some constants h0 and r:

h(x) = h0 – r/x

Proof of this is straightforward, though to keep it simple I’ve hand-waved why it’s a power law:

Given

h'(2x) = 1/4 h'(x)

Let

h'(x) = r x^n

h'(2x) = r (2x)^n

r (2x)^n = 1/4 r x^n

n = -2

h'(x) = r/x^2

h(x) = – r x^(-1) + C

h(x) = h0 – r/x

Miles Kimball also has some more discussion on his blog about how a utility function of this form works. (His statement about redistribution at the end is kind of baffling though; sure, dollar for dollar, redistributing wealth from the middle class to the poor would produce a higher gain in utility than redistributing wealth from the rich to the middle class. But neither is as good as redistributing from the rich to the poor, and the rich have a lot more dollars to redistribute.)

Satisfaction, however, must obey logarithmic utility, like this, for some constants s0 and k.

The x+1 means that it takes slightly less proportionally to have the same effect as your wealth increases, but it allows the function to be equal to s0 at x=0 instead of going to negative infinity:

s(x) = s0 + k ln(x)

Proof of this is very simple, almost trivial:

Given

s'(x) = k/x

s(x) = k ln(x) + s0

Both of these functions actually have a serious problem that as x approaches zero, they go to negative infinity. For self-directed utility this almost makes sense (if your real consumption goes to zero, you die), but it makes no sense at all for other-directed utility, and since there are causes most of us would willingly die for, the disutility of dying should be large, but not infinite.

Therefore I think it’s probably better to use x +1 in place of x:

h(x) = h0 – r/(x+1)

s(x) = s0 + k ln(x+1)

This makes s0 the baseline satisfaction of having no other-directed spending, though the baseline happiness of zero self-directed spending is actually h0 – r rather than just h0. If we want it to be h0, we could use this form instead:

h(x) = h0 + r x/(x+1)

This looks quite different, but actually only differs by a constant.

Therefore, my final answer for the utility of wealth (or possibly income, or spending? I’m not sure which interpretation is best just yet) is actually this:

u(x) = h(x) + s(x)

h(x) = h0 + r x/(x+1)

s(x) = s0 + k ln(x+1)

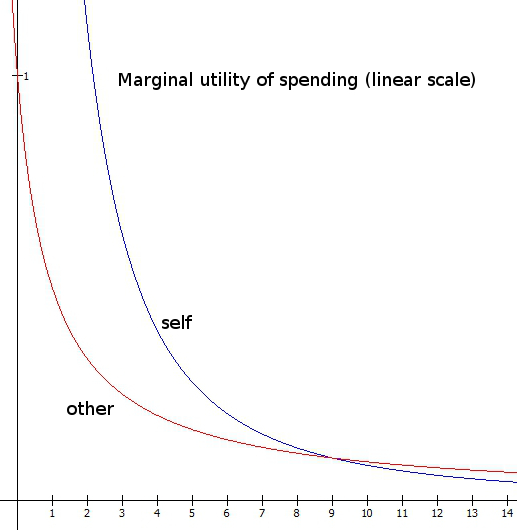

Marginal utility is then the derivatives of these:

h'(x) = r/(x+1)^2

s'(x) = k/(x+1)

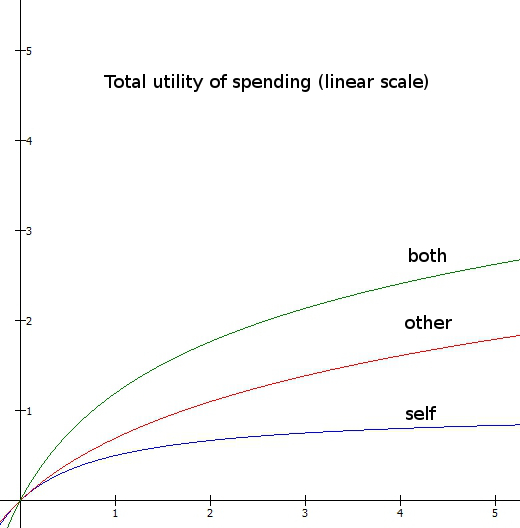

Let’s assign some values to the constants so that we can actually graph these.

Let h0 = s0 = 0, so our baseline is just zero.

Furthermore, let r = k = 1, which would mean that the value of $1 is the same whether spent either on yourself or on others, if $1 is all you have. (This is probably wrong, actually, but it’s the simplest to start with. Shortly I’ll discuss what happens as you vary the ratio k/r.)

Here is the result graphed on a linear scale:

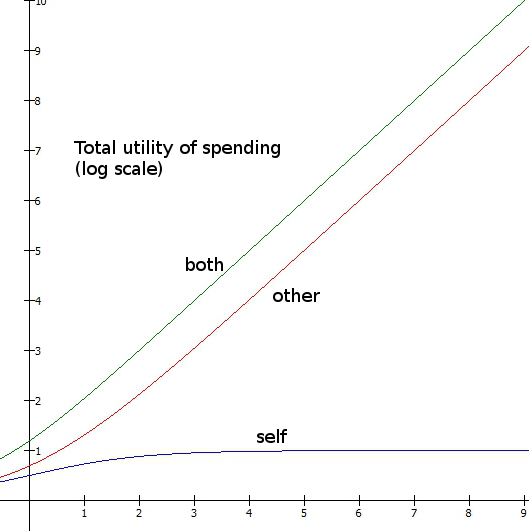

And now, graphed with wealth on a logarithmic scale:

As you can see, self-directed marginal utility drops off much faster than other-directed marginal utility, so the amount you spend on others relative to yourself rapidly increases as your wealth increases. If that doesn’t sound right, remember that I’m including Veblen goods as “other-directed”; when you buy a Ferrari, it’s not really for yourself. While proportional rates of charitable donation do not increase as wealth increases (it’s actually a U-shaped pattern, largely driven by poor people giving to religious institutions), they probably should (people should really stop giving to religious institutions! Even the good ones aren’t cost-effective, and some are very, very bad.). Furthermore, if you include spending on relative power and status as the other-directed motive, that kind of spending clearly does proportionally increase as wealth increases—gotta keep up with those Joneses.

If r/k = 1, that basically means you value others exactly as much as yourself, which I think is implausible (maybe some extreme altruists do that, and Peter Singer seems to think this would be morally optimal). r/k < 1 would mean you should never spend anything on yourself, which not even Peter Singer believes. I think r/k = 10 is a more reasonable estimate.

For any given value of r/k, there is an optimal ratio of self-directed versus other-directed spending, which can vary based on your total wealth.

Actually deriving what the optimal proportion would be requires a whole lot of algebra in a post that probably already has too much algebra, but the point is, there is one, and it will depend strongly on the ratio r/k, that is, the overall relative importance of self-directed versus other-directed motivation.

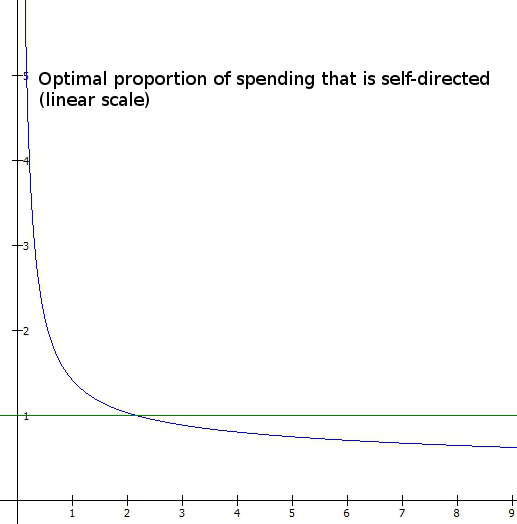

Take a look at this graph, which uses r/k = 10.

If you only have 2 to spend, you should spend it entirely on yourself, because up to that point the marginal utility of self-directed spending is always higher. If you have 3 to spend, you should spend most of it on yourself, but a little bit on other people, because after you’ve spent about 2.2 on yourself there is more marginal utility for spending on others than on yourself.

If your available wealth is W, you would spend some amount x on yourself, and then W-x on others:

u(x) = h(x) + s(W-x)

u(x) = r x/(x+1) + k ln(W – x + 1)

Then you take the derivative and set it equal to zero to find the local maximum. I’ll spare you the algebra, but this is the result of that optimization:

x = – 1 – r/(2k) + sqrt(r/k) sqrt(2 + W + r/(4k))

As long as k <= r (which more or less means that you care at least as much about yourself as about others—I think this is true of basically everyone) then as long as W > 0 (as long as you have some money to spend) we also have x > 0 (you will spend at least something on yourself).

Below a certain threshold (depending on r/k), the optimal value of x is greater than W, which means that, if possible, you should be receiving donations from other people and spending them on yourself. (Otherwise, just spend everything on yourself). After that, x < W, which means that you should be donating to others. The proportion that you should be donating smoothly increases as W increases, as you can see on this graph (which uses r/k = 10, a figure I find fairly plausible):

While I’m sure no one literally does this calculation, most people do seem to have an intuitive sense that you should donate an increasing proportion of your income to others as your income increases, and similarly that you should pay a higher proportion in taxes. This utility function would justify that—which is something that most proposed utility functions cannot do. In most models there is a hard cutoff where you should donate nothing up to the point where your marginal utility is equal to the marginal utility of donating, and then from that point forward you should donate absolutely everything. Maybe a case can be made for that ethically, but psychologically I think it’s a non-starter.

I’m still not sure exactly how to test this empirically. It’s already quite difficult to get people to answer questions about marginal utility in a way that is meaningful and coherent (people just don’t think about questions like “Which is worth more? $4 to me now or $10 if I had twice as much wealth?” on a regular basis). I’m thinking maybe they could play some sort of game where they have the opportunity to make money at the game, but must perform tasks or bear risks to do so, and can then keep the money or donate it to charity. The biggest problem I see with that is that the amounts would probably be too small to really cover a significant part of anyone’s total wealth, and therefore couldn’t cover much of their marginal utility of wealth function either. (This is actually a big problem with a lot of experiments that use risk aversion to try to tease out marginal utility of wealth.) But maybe with a variety of experimental participants, all of whom we get income figures on?