July 23, JDN 2457593

Depending on your preconceptions, this statement may seem either eminently trivial or offensively wrong: Lukewarm support is a lot better than opposition.

I’ve always been in the “trivial” camp, so it has taken me awhile to really understand where people are coming from when they say things like the following.

From a civil rights activist blogger (“POC” being “person of color” in case you didn’t know):

“Many of my POC friends would actually prefer to hang out with an Archie Bunker-type who spits flagrantly offensive opinions, rather than a colorblind liberal whose insidious paternalism, dehumanizing tokenism, and cognitive indoctrination ooze out between superficially progressive words.

Right-wing racists are much more honest, and thus easier to deal with, than liberal racists.

From a Libertarian blogger:

I can deal with someone opposing me because of my politics. I can deal with someone who attacks me because of my religious beliefs. I can deal with open hostility. I know where I stand with people like that.

They hate me or my actions for (insert reason here). Fine, that is their choice. Let’s move onto the next bit. I’m willing to live and let live if they are.

But I don’t like someone buttering me up because they need my support, only to drop me the first chance they get. I don’t need sweet talk to distract me from the knife at my back. I don’t need someone promising the world just so they can get a boost up.

In each of these cases, people are expressing a preference for dealing with someone who actively opposes them, rather than someone who mostly supports them. That’s really weird.

The basic fact that lukewarm support is better than opposition is basically a mathematical theorem. In a democracy or anything resembling one, if you have the majority of population supporting you, even if they are all lukewarm, you win; if you have the majority of the population opposing you, even if the remaining minority is extremely committed to your cause, you lose.

Yes, okay, it does get slightly more complicated than that, as in most real-world democracies small but committed interest groups actually can pressure policy more than lukewarm majorities (the special interest effect); but even then, you are talking about the choice between no special interests and a special interest actively against you.

There is a valid question of whether it is more worthwhile to get a small, committed coalition, or a large, lukewarm coalition; but at the individual level, it is absolutely undeniable that supporting you is better for you than opposing you, full stop. I mean that in the same sense that the Pythagorean theorem is undeniable; it’s a theorem, it has to be true.

If you had the opportunity to immediately replace every single person who opposes you with someone who supports you but is lukewarm about it, you’d be insane not to take it. Indeed, this is basically how all social change actually happens: Committed supporters persuade committed opponents to become lukewarm supporters, until they get a majority and start winning policy votes.

If this is indeed so obvious and undeniable, why are there so many people… trying to deny it?

I came to realize that there is a deep psychological effect at work here. I could find very little in the literature describing this effect, which I’m going to call heretic effect (though the literature on betrayal aversion, several examples of which are linked in this sentence, is at least somewhat related).

Heretic effect is the deeply-ingrained sense human beings tend to have (as part of the overall tribal paradigm) that one of the worst things you can possibly do is betray your tribe. It is worse than being in an enemy tribe, worse even than murdering someone. The one absolutely inviolable principle is that you must side with your tribe.

This is one of the biggest barriers to police reform, by the way: The Blue Wall of Silence is the result of police officers identifying themselves as a tight-knit tribe and refusing to betray one of their own for anything. I think the best option for convincing police officers to support reform is to reframe violations of police conduct as themselves betrayals—the betrayal is not the IA taking away your badge, the betrayal is you shooting an unarmed man because he was Black.

Heretic effect is a particular form of betrayal aversion, where we treat those who are similar to our tribe but not quite part of it as the very worst sort of people, worse than even our enemies, because at least our enemies are not betrayers. In fact it isn’t really betrayal, but it feels like betrayal.

I call it “heretic effect” because of the way that exclusivist religions (including all the Abrahamaic religions, and especially Christianity and Islam) focus so much of their energy on rooting out “heretics”, people who almost believe the same as you do but not quite. The Spanish Inquisition wasn’t targeted at Buddhists or even Muslims; it was targeted at Christians who slightly disagreed with Catholicism. Why? Because while Buddhists might be the enemy, Protestants were betrayers. You can still see this in the way that Muslim societies treat “apostates”, those who once believed in Islam but don’t anymore. Indeed, the very fact that Christianity and Islam are at each other’s throats, rather than Hinduism and atheism, shows that it’s the people who almost agree with you that really draw your hatred, not the people whose worldview is radically distinct.

This is the effect that makes people dislike lukewarm supporters; like heresy, lukewarm support feels like betrayal. You can clearly hear that in the last quote: “I don’t need sweet talk to distract me from the knife at my back.” Believe it or not, Libertarians, my support for replacing the social welfare state with a basic income, decriminalizing drugs, and dramatically reducing our incarceration rate is not deception. Nor do I think I’ve been particularly secretive about my desire to make taxes more progressive and environmental regulations stronger, the things you absolutely don’t agree with. Agreeing with you on some things but not on other things is not in fact the same thing as lying to you about my beliefs or infiltrating and betraying your tribe.

That said, I do sort of understand why it feels that way. When I agree with you on one thing (decriminalizing cannabis, for instance), it sends you a signal: “This person thinks like me.” You may even subconsciously tag me as a fellow Libertarian. But then I go and disagree with you on something else that’s just as important (strengthening environmental regulations), and it feels to you like I have worn your Libertarian badge only to stab you in the back with my treasonous environmentalism. I thought you were one of us!

Similarly, if you are a social justice activist who knows all the proper lingo and is constantly aware of “checking your privilege”, and I start by saying, yes, racism is real and terrible, and we should definitely be working to fight it, but then I question something about your language and approach, that feels like a betrayal. At least if I’d come in wearing a Trump hat you could have known which side I was really on. (And indeed, I have had people unfriend me or launch into furious rants at me for questioning the orthodoxy in this way. And sure, it’s not as bad as actually being harassed on the street by bigots—a thing that has actually happened to me, by the way—but it’s still bad.)

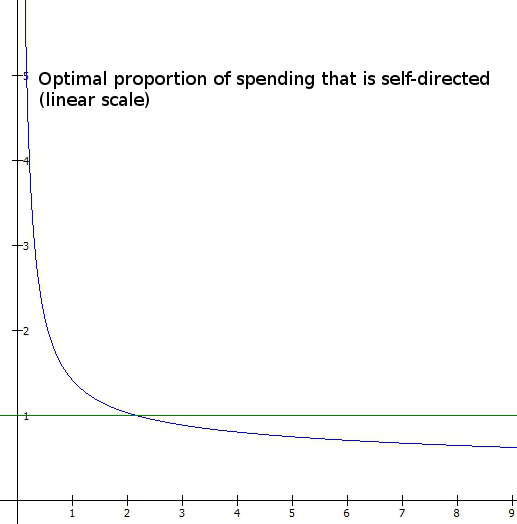

But if you can resist this deep-seated impulse and really think carefully about what’s happening here, agreeing with you partially clearly is much better than not agreeing with you at all. Indeed, there’s a fairly smooth function there, wherein the more I agree with your goals the more our interests are aligned and the better we should get along. It’s not completely smooth, because certain things are sort of package deals: I wouldn’t want to eliminate the social welfare system without replacing it with a basic income, whereas many Libertarians would. I wouldn’t want to ban fracking unless we had established a strong nuclear infrastructure, but many environmentalists would. But on the whole, more agreement is better than less agreement—and really, even these examples are actually surface-level results of deeper disagreement.

Getting this reaction from social justice activists is particularly frustrating, because I am on your side. Bigotry corrupts our society at a deep level and holds back untold human potential, and I want to do my part to undermine and hopefully one day destroy it. When I say that maybe “privilege” isn’t the best word to use and warn you about not implicitly ascribing moral responsibility across generations, this is not me being a heretic against your tribe; this is a strategic policy critique. If you are writing a letter to the world, I’m telling you to leave out paragraph 2 and correcting your punctuation errors, not crumpling up the paper and throwing it into a fire. I’m doing this because I want you to win, and I think that your current approach isn’t working as well as it should. Maybe I’m wrong about that—maybe paragraph 2 really needs to be there, and you put that semicolon there on purpose—in which case, go ahead and say so. If you argue well enough, you may even convince me; if not, this is the sort of situation where we can respectfully agree to disagree. But please, for the love of all that is good in the world, stop saying that I’m worse than the guys in the KKK hoods. Resist that feeling of betrayal so that we can have a constructive critique of our strategy. Don’t do it for me; do it for the cause.