JDN 2457411

The United States is slowly dragging itself out of the Second Depression.

Unemployment fell from almost 10% to about 5%.

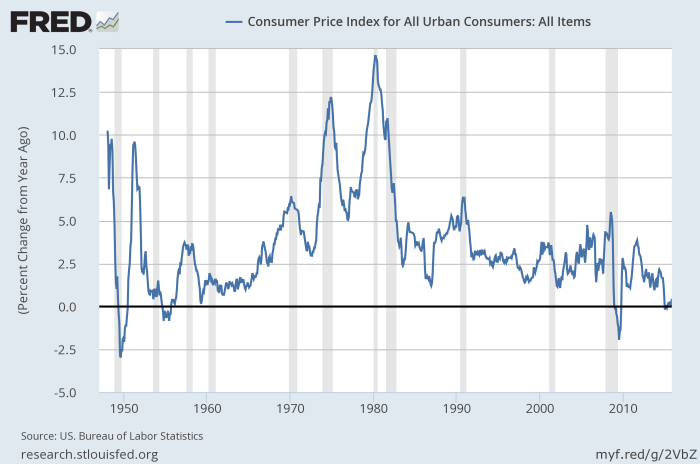

Core inflation has been kept between 0% and 2% most of the time.

Overall inflation has been within a reasonable range:

Real GDP has returned to its normal growth trend, though with a permanent loss of output relative to what would have happened without the Great Recession.

Consumption spending is also back on trend, tracking GDP quite precisely.

The Federal Reserve even raised the federal funds interest rate above the zero lower bound, signaling a return to normal monetary policy. (As I argued previously, I’m pretty sure that was their main goal actually.)

Employment remains well below the pre-recession peak, but is now beginning to trend upward once more.

The only thing that hasn’t recovered is labor force participation, which continues to decline. This is how we can have unemployment go back to normal while employment remains depressed; people leave the labor force by retiring, going back to school, or simply giving up looking for work. By the formal definition, someone is only unemployed if they are actively seeking work. No, this is not new, and it is certainly not Obama rigging the numbers. This is how we have measured unemployment for decades.

Actually, it’s kind of the opposite: Since the Clinton administration we’ve also kept track of “broad unemployment”, which includes people who’ve given up looking for work or people who have some work but are trying to find more. But we can’t directly compare it to anything that happened before 1994, because the BLS didn’t keep track of it before then. All we can do is estimate based on what we did measure. Based on such estimation, it is likely that broad unemployment in the Great Depression may have gotten as high as 50%. (I’ve found that one of the best-fitting models is actually one of the simplest; assume that broad unemployment is 1.8 times narrow unemployment. This fits much better than you might think.)

So, yes, we muddle our way through, and the economy eventually heals itself. We could have brought the economy back much sooner if we had better fiscal policy, but at least our monetary policy was good enough that we were spared the worst.

But I think most of us—especially in my generation—recognize that it is still really hard to get a job. Overall GDP is back to normal, and even unemployment looks all right; but why are so many people still out of work?

I have a hypothesis about this: I think a major part of why it is so hard to recover from recessions is that our system of hiring is terrible.

Contrary to popular belief, layoffs do not actually substantially increase during recessions. Quits are substantially reduced, because people are afraid to leave current jobs when they aren’t sure of getting new ones. As a result, rates of job separation actually go down in a recession. Job separation does predict recessions, but not in the way most people think. One of the things that made the Great Recession different from other recessions is that most layoffs were permanent, instead of temporary—but we’re still not sure exactly why.

Here, let me show you some graphs from the BLS.

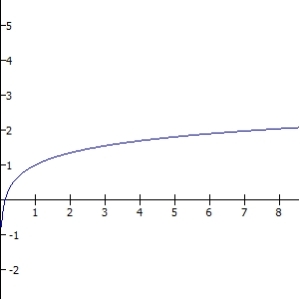

This graph shows job openings from 2005 to 2015:

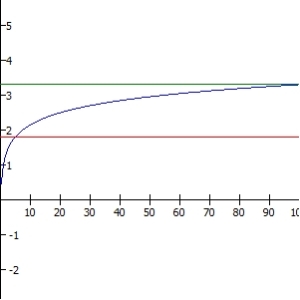

This graph shows hires from 2005 to 2015:

Both of those show the pattern you’d expect, with openings and hires plummeting in the Great Recession.

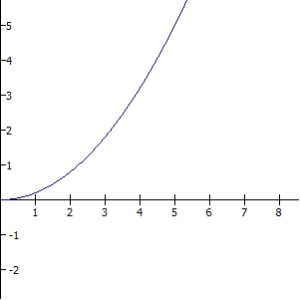

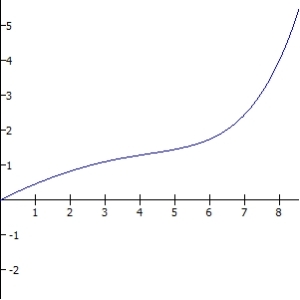

But check out this graph, of job separations from 2005 to 2015:

Same pattern!

Unemployment in the Second Depression wasn’t caused by a lot of people losing jobs. It was caused by a lot of people not getting jobs—either after losing previous ones, or after graduating from school. There weren’t enough openings, and even when there were openings there weren’t enough hires.

Part of the problem is obviously just the business cycle itself. Spending drops because of a financial crisis, then businesses stop hiring people because they don’t project enough sales to justify it; then spending drops even further because people don’t have jobs, and we get caught in a vicious cycle.

But we are now recovering from the cyclical downturn; spending and GDP are back to their normal trend. Yet the jobs never came back. Something is wrong with our hiring system.

So what’s wrong with our hiring system? Probably a lot of things, but here’s one that’s been particularly bothering me for a long time.

As any job search advisor will tell you, networking is essential for career success.

There are so many different places you can hear this advice, it honestly gets tiring.

But stop and think for a moment about what that means. One of the most important determinants of what job you will get is… what people you know?

It’s not what you are best at doing, as it would be if the economy were optimally efficient.

It’s not even what you have credentials for, as we might expect as a second-best solution.

It’s not even how much money you already have, though that certainly is a major factor as well.

It’s what people you know.

Now, I realize, this is not entirely beyond your control. If you actively participate in your community, attend conferences in your field, and so on, you can establish new contacts and expand your network. A major part of the benefit of going to a good college is actually the people you meet there.

But a good portion of your social network is more or less beyond your control, and above all, says almost nothing about your actual qualifications for any particular job.

There are certain jobs, such as marketing, that actually directly relate to your ability to establish rapport and build weak relationships rapidly. These are a tiny minority. (Actually, most of them are the sort of job that I’m not even sure needs to exist.)

For the vast majority of jobs, your social skills are a tiny, almost irrelevant part of the actual skill set needed to do the job well. This is true of jobs from writing science fiction to teaching calculus, from diagnosing cancer to flying airliners, from cleaning up garbage to designing spacecraft. Social skills are rarely harmful, and even often provide some benefit, but if you need a quantum physicist, you should choose the recluse who can write down the Dirac equation by heart over the well-connected community leader who doesn’t know what an integral is.

At the very least, it strains credibility to suggest that social skills are so important for every job in the world that they should be one of the defining factors in who gets hired. And make no mistake: Networking is as beneficial for landing a job at a local bowling alley as it is for becoming Chair of the Federal Reserve. Indeed, for many entry-level positions networking is literally all that matters, while advanced positions at least exclude candidates who don’t have certain necessary credentials, and then make the decision based upon who knows whom.

Yet, if networking is so inefficient, why do we keep using it?

I can think of a couple reasons.

The first reason is that this is how we’ve always done it. Indeed, networking strongly pre-dates capitalism or even money; in ancient tribal societies there were certainly jobs to assign people to: who will gather berries, who will build the huts, who will lead the hunt. But there were no colleges, no certifications, no resumes—there was only your position in the social structure of the tribe. I think most people simply automatically default to a networking-based system without even thinking about it; it’s just the instinctual System 1 heuristic.

One of the few things I really liked about Debt: The First 5000 Years was the discussion of how similar the behavior of modern CEOs is to that of ancient tribal chieftans, for reasons that make absolutely no sense in terms of neoclassical economic efficiency—but perfect sense in light of human evolution. I wish Graeber had spent more time on that, instead of many of these long digressions about international debt policy that he clearly does not understand.

But there is a second reason as well, a better reason, a reason that we can’t simply give up on networking entirely.

The problem is that many important skills are very difficult to measure.

College degrees do a decent job of assessing our raw IQ, our willingness to persevere on difficult tasks, and our knowledge of the basic facts of a discipline (as well as a fantastic job of assessing our ability to pass standardized tests!). But when you think about the skills that really make a good physicist, a good economist, a good anthropologist, a good lawyer, or a good doctor—they really aren’t captured by any of the quantitative metrics that a college degree provides. Your capacity for creative problem-solving, your willingness to treat others with respect and dignity; these things don’t appear in a GPA.

This is especially true in research: The degree tells how good you are at doing the parts of the discipline that have already been done—but what we really want to know is how good you’ll be at doing the parts that haven’t been done yet.

Nor are skills precisely aligned with the content of a resume; the best predictor of doing something well may in fact be whether you have done so in the past—but how can you get experience if you can’t get a job without experience?

These so-called “soft skills” are difficult to measure—but not impossible. Basically the only reliable measurement mechanisms we have require knowing and working with someone for a long span of time. You can’t read it off a resume, you can’t see it in an interview (interviews are actually a horribly biased hiring mechanism, particularly biased against women). In effect, the only way to really know if someone will be good at a job is to work with them at that job for awhile.

There’s a fundamental information problem here I’ve never quite been able to resolve. It pops up in a few other contexts as well: How do you know whether a novel is worth reading without reading the novel? How do you know whether a film is worth watching without watching the film? When the information about the quality of something can only be determined by paying the cost of purchasing it, there is basically no way of assessing the quality of things before we purchase them.

Networking is an attempt to get around this problem. To decide whether to read a novel, ask someone who has read it. To decide whether to watch a film, ask someone who has watched it. To decide whether to hire someone, ask someone who has worked with them.

The problem is that this is such a weak measure that it’s not much better than no measure at all. I often wonder what would happen if businesses were required to hire people based entirely on resumes, with no interviews, no recommendation letters, and any personal contacts treated as conflicts of interest rather than useful networking opportunities—a world where the only thing we use to decide whether to hire someone is their documented qualifications. Could it herald a golden age of new economic efficiency and job fulfillment? Or would it result in widespread incompetence and catastrophic collapse? I honestly cannot say.