Mar 16 JDN 2460751

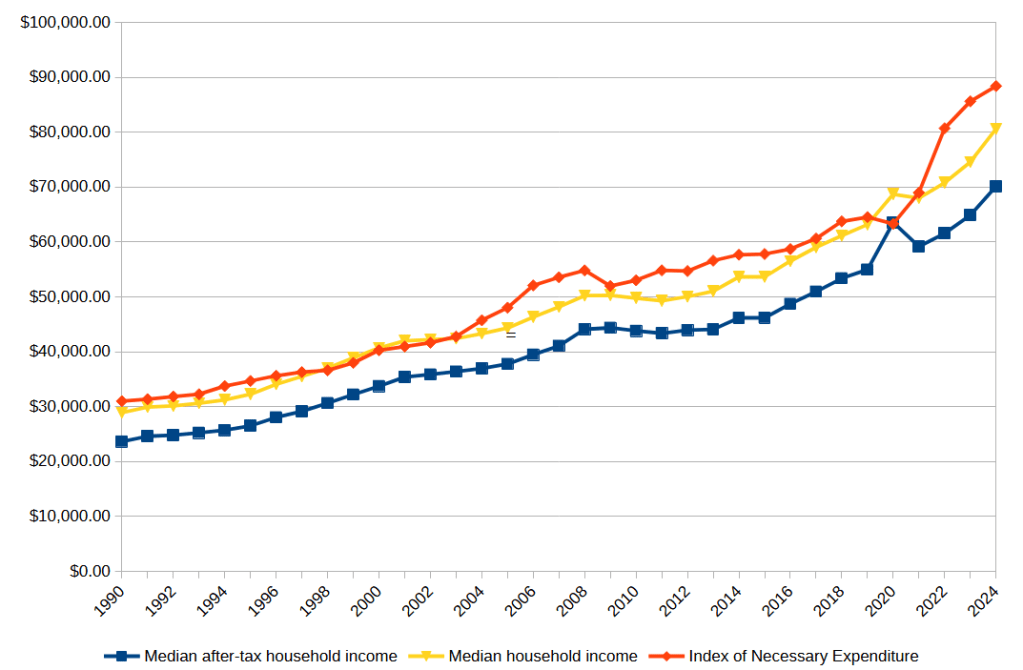

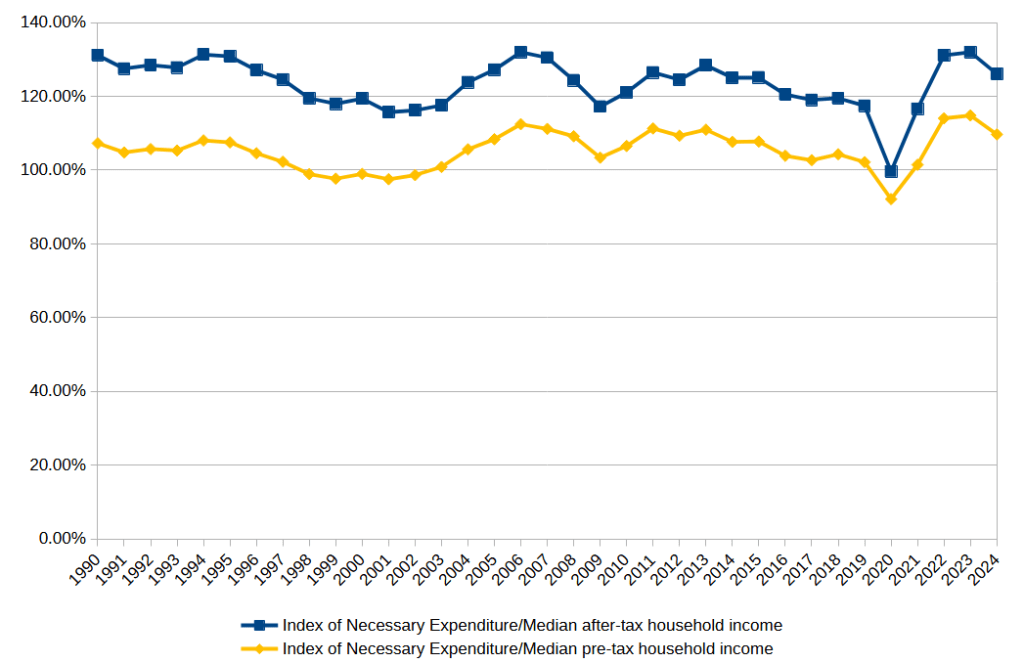

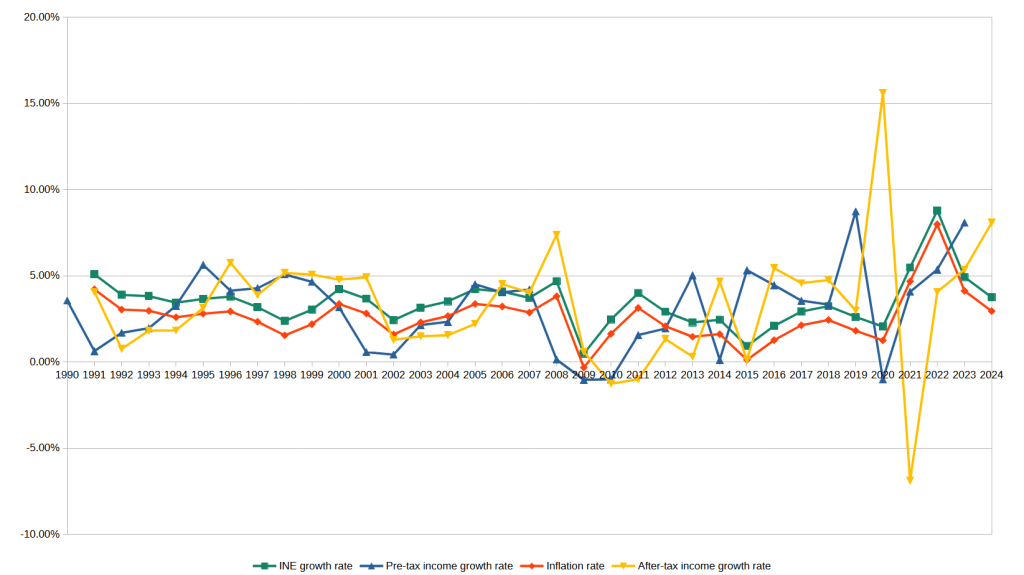

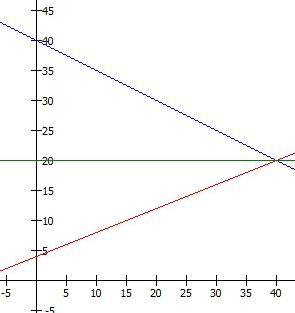

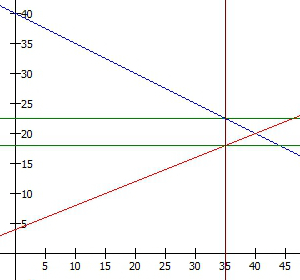

In last week’s post I constructed an Index of National Expenditure (INE), attempting to estimate the total cost of all of the things a family needs and can’t do without, like housing, food, clothing, cars, healthcare, and education. What I found shocked me: The median family cannot afford all necessary expenditures.

I have a couple more thoughts about that.

I still don’t understand why people care so much about gas prices.

Gasoline was a relatively small contribution to INE. It was more than clothing but less than utilities, and absolutely dwarfed by housing, food, or college. I thought maybe since I only counted a 15-mile commute, maybe I didn’t actually include enoughgasoline usage, but based on this estimate of about $2000 per driver, I was in about the right range; my estimate for the same year was $3350 for a 2-car family.

I think I still have to go with my salience hypothesis: Gasoline is the only price that we plaster in real-time on signs on the side of the road. So people are constantly aware of it, even though it isn’t actually that important.

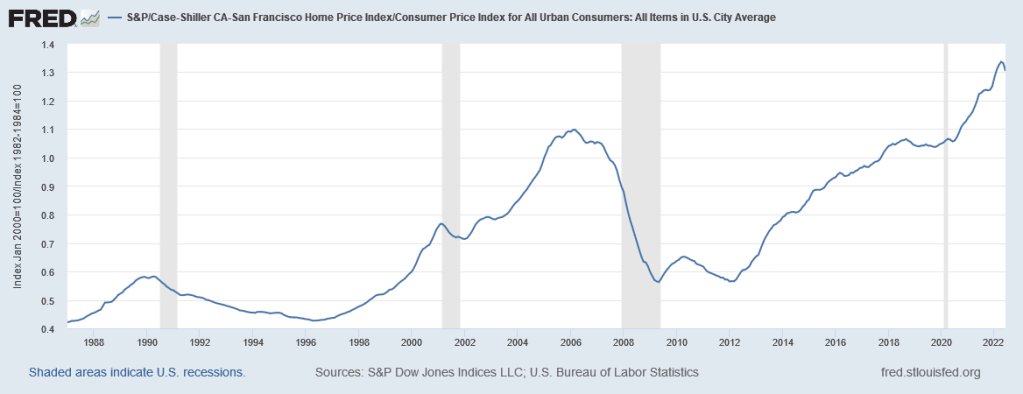

The price surge that should be upsetting people is housing.

If the price of homes had only risen with the rate of CPI inflation instead of what it actually did, the median home price in 2024 would be only $234,000 instead of the $396,000 it actually is; and by my estimation that would save a typical family $11,000 per year—a whopping 15% of their income, and nearly enough to make the INE affordable by itself.

Now, I’ll consider some possible objections to my findings.

Objection 1: A typical family doesn’t actually spend this much on these things.

You’re right, they don’t! Because they couldn’t possibly. Even with substantial debt, you just can’t sustainably spend 125% of your after-tax household income.

My goal here was not to estimate how much families actually spend; it was to estimate how much they need to spend in order to live a good life and not feel deprived.

What I have found is that most American families feel deprived. They are forced to sacrifice something really important—like healthcare, or education, or owning a home—because they simply can’t afford it.

What I’m trying to do here is find the price of the American Dream; and what I’ve found is that the American Dream has a price that most Americans cannot afford.

Objection 2: You should use median healthcare spending, not mean.

I did in fact use mean figures instead of median for healthcare expenditures, mainly because only the mean was readily available. Mean income is higher than median income, so you might say that I’ve overestimated healthcare expenditure—and in a sense that’s definitely true. The median family spends less than this on healthcare.

But the reason that the median family spends less than this on healthcare is not that they want to, but that they have to. Healthcare isn’t a luxury that people buy more of because they are richer. People buy either as much as they need or as much as they can afford—whichever is lower, which is typically the latter. Using the mean instead of the median is a crude way to account for that, but I think it’s a defensible one.

But okay, let’s go ahead and cut the estimate of healthcare spending in half; even if you do that, the INE is still larger than after-tax median household income in most years.

Objection 3: A typical family isn’t a family of four, it’s a family of three.

Yes, the mean number of people in a family household in the US is 3.22 (the median is 3).

This is a very bad thing.

Part of what I seem to be finding here is that a family of four is unaffordable—literally impossible to afford—on a typical family income.

But a healthy society is one in which typical families have two or three children. That is what we need in order to achieve population replacement. When families get smaller than that, we aren’t having enough children, and our population will decline—which means that we’ll have too many old people relative to young people. This puts enormous pressure on healthcare and pension systems, which rely upon the fact that young people produce more, in order to pay for the fact that old people cost more.

The ideal average number of births per woman is about 2.1; this is what would give us a steady population. No US state has fertility above this level. The only reason the US population is growing rather than shrinking is that we are taking in immigrants.

This is bad. This is not sustainable. If the reason families aren’t having enough kids is that they can’t afford them—and this fits with other research on the subject—then this economic failure damages our entire society, and it needs to be fixed.

Objection 4: Many families buy their cars used.

Perhaps 1/10 of a new car every year isn’t an ideal estimate of how much people spend on their cars, but if anything I think it’s conservative, because if you only buy a car every 10 years, and it was already used when you bought it, you’re going to need to spend a lot on maintaining it—quite possibly more than it would cost to get a new one. Motley Fool actually estimates the ownership cost of just one car at substantially more than I estimated for two cars. So if anything your complaint should be that I’ve underestimated the cost by not adequately including maintenance and insurance.

Objection 5: Not everyone gets a four-year college degree.

Fair enough; a substantial proportion get associate’s degrees, and most people get no college degree at all. But some also get graduate degrees, which is even more expensive (ask me how I know).

Moreover, in today’s labor market, having a college degree makes a huge difference in your future earnings; a bachelor’s degree increases your lifetime earnings by a whopping 84%. In theory it’s okay to have a society where most people don’t go to college; in practice, in our society, not going to college puts you at a tremendous disadvantage for the rest of your life. So we either need to find a way to bring wages up for those who don’t go to college, or find a way to bring the cost of college down.

This is probably one of the things that families actually choose to scrimp on, only sending one kid to college or none at all. But because college is such a huge determinant of earnings, this perpetuates intergenerational inequality: Only rich families can afford to send their kids to college, and only kids who went to college grow up to have rich families.

Objection 6: You don’t actually need to save for college; you can use student loans.

Yes, you can, and in practice, most people who to college do. But while this solves the liquidity problem (having enough money right now), it does not solve the solvency problem (having enough money in the long run). Failing to save for college and relying on student loans just means pushing the cost of college onto your children—and since we’ve been doing that for over a generation, feel free to replace the category “college savings” with “repaying student loans”; it won’t meaningfully change the results.