August 3, JDN 2457604

I finally began to understand the bizarre and terrifying phenomenon that is the Donald Trump Presidential nomination when I watched this John Oliver episode:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U-l3IV_XN3c

These lines in particular, near the end, finally helped me put it all together:

What is truly revealing is his implication that believing something to be true is the same as it being true. Because if anything, that was the theme of the Republican Convention this week; it was a four-day exercise in emphasizing feelings over facts.

The facts against Donald Trump are absolutely overwhelming. He is not even a competent business man, just a spectacularly manipulative one—and even then, it’s not clear he made any more money than he would have just keeping his inheritance in a diversified stock portfolio. His casinos were too fraudulent for Atlantic City. His university was fraudulent. He has the worst honesty rating Politifact has ever given a candidate. (Bernie Sanders, Barack Obama, and Hillary Clinton are statistically tied for some of the best.)

More importantly, almost every policy he has proposed or even suggested is terrible, and several of them could be truly catastrophic.

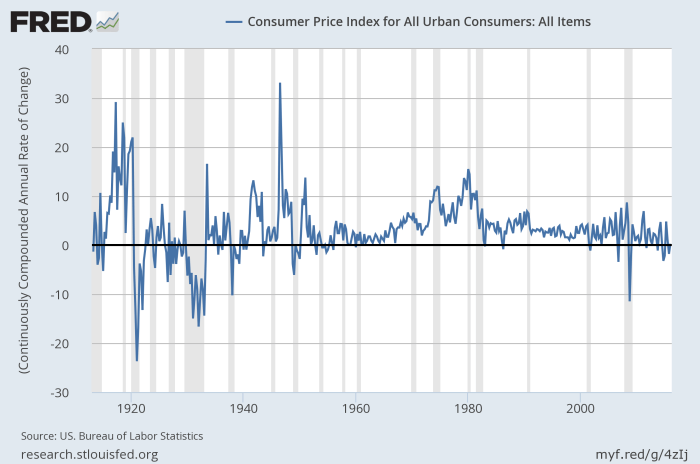

Let’s start with economic policy: His trade policy would set back decades of globalization and dramatically increase global poverty, while doing little or nothing to expand employment in the US, especially if it sparks a trade war. His fiscal policy would permanently balloon the deficit by giving one of the largest tax breaks to the rich in history. His infamous wall would probably cost about as much as the federal government currently spends on all basic scientific research combined, and his only proposal for funding it fundamentally misunderstands how remittances and trade deficits work. He doesn’t believe in climate change, and would roll back what little progress we have made at reducing carbon emissions, thereby endangering millions of lives. He could very likely cause a global economic collapse comparable to the Great Depression.

His social policy is equally terrible: He has proposed criminalizing abortion, (in express violation of Roe v. Wade) which even many pro-life people find too extreme. He wants to deport all Muslims and ban Muslims from entering, which not just a direct First Amendment violation but also literally involves jackbooted soldiers breaking into the homes of law-abiding US citizens to kidnap them and take them out of the country. He wants to deport 11 million undocumented immigrants, the largest deportation in US history.

Yet it is in foreign policy above all that Trump is truly horrific. He has explicitly endorsed targeting the families of terrorists, which is a war crime (though not as bad as what Ted Cruz wanted to do, which is carpet-bombing cities). Speaking of war crimes, he thinks our torture policy wasn’t severe enough, and doesn’t even care if it is ineffective. He has made the literally mercantilist assertion that the purpose of military alliances is to create trade surpluses, and if European countries will not provide us with trade surpluses (read: tribute), he will no longer commit to defending them, thereby undermining decades of global stability that is founded upon America’s unwavering commitment to defend our allies. And worst of all, he will not rule out the first-strike deployment of nuclear weapons.

I want you to understand that I am not exaggerating when I say that a Donald Trump Presidency carries a nontrivial risk of triggering global nuclear war. Will this probably happen? No. It has a probability of perhaps 1%. But a 1% chance of a billion deaths is not a risk anyone should be prepared to take.

All of these facts scream at us that Donald Trump would be a catastrophe for America and the world. Why, then, are so many people voting for him? Why do our best election forecasts give him a good chance of winning the election?

Because facts don’t speak for themselves.

This is how the left, especially the center-left, has dropped the ball in recent decades. We joke that reality has a liberal bias, because so many of the facts are so obviously on our side. But meanwhile the right wing has nodded and laughed, even mockingly called us the “reality-based community”, because they know how to manipulate feelings.

Donald Trump has essentially no other skills—but he has that one, and it is enough. He knows how to fan the flames of anger and hatred and point them at his chosen targets. He knows how to rally people behind meaningless slogans like “Make America Great Again” and convince them that he has their best interests at heart.

Indeed, Trump’s persuasiveness is one of his many parallels with Adolf Hitler; I am not yet prepared to accuse Donald Trump of seeking genocide, yet at the same time I am not yet willing to put it past him. I don’t think it would take much of a spark at this point to trigger a conflagration of hatred that launches a genocide against Muslims in the United States, and I don’t trust Trump not to light such a spark.

Meanwhile, liberal policy wonks are looking on in horror, wondering how anyone could be so stupid as to believe him—and even publicly basically calling people stupid for believing him. Or sometimes we say they’re not stupid, they’re just racist. But people don’t believe Donald Trump because they are stupid; they believe Donald Trump because he is persuasive. He knows the inner recesses of the human mind and can harness our heuristics to his will. Do not mistake your unique position that protects you—some combination of education, intellect, and sheer willpower—for some inherent superiority. You are not better than Trump’s followers; you are more resistant to Trump’s powers of persuasion. Yes, statistically, Trump voters are more likely to be racist; but racism is a deep-seated bias in the human mind that to some extent we all share. Trump simply knows how to harness it.

Our enemies are persuasive—and therefore we must be as well. We can no longer act as though facts will automatically convince everyone by the power of pure reason; we must learn to stir emotions and rally crowds just as they do.

Or rather, not just as they do—not quite. When we see lies being so effective, we may be tempted to lie ourselves. When we see people being manipulated against us, we may be tempted to manipulate them in return. But in the long run, we can’t afford to do that. We do need to use reason, because reason is the only way to ensure that the beliefs we instill are true.

Therefore our task must be to make people see reason. Let me be clear: Not demand they see reason. Not hope they see reason. Not lament that they don’t. This will require active investment on our part. We must actually learn to persuade people in such a manner that their minds become more open to reason. This will mean using tools other than reason, but it will also mean treading a very fine line, using irrationality only when rationality is insufficient.

We will be tempted to take the easier, quicker path to the Dark Side, but we must resist. Our goal must be not to make people do what we want them to—but to do what they would want to if they were fully rational and fully informed. We will need rhetoric; we will need oratory; we may even need some manipulation. But as we fight our enemy, we must be vigilant not to become them.

This means not using bad arguments—strawmen and conmen—but pointing out the flaws in our opponents’ arguments even when they seem obvious to us—bananamen. It means not overstating our case about free trade or using implausible statistical results simply because they support our case.

But it also means not understating our case, not hiding in page 17 of an opaque technical report that if we don’t do something about climate change right now millions of people will die. It means not presenting our ideas as “political opinions” when they are demonstrated, indisputable scientific facts. It means taking the media to task for their false balance that must find a way to criticize a Democrat every time they criticize a Republican: Sure, he is a pathological liar and might trigger global economic collapse or even nuclear war, but she didn’t secure her emails properly. If you objectively assess the facts and find that Republicans lie three times as often as Democrats, maybe that’s something you should be reporting on instead of trying to compensate for by changing your criteria.

Speaking of the media, we should be pressuring them to include a regular—preferably daily, preferably primetime—segment on climate change, because yes, it is that important. How about after the weather report every day, you show a climate scientist explaining why we keep having record-breaking summer heat and more frequent natural disasters? If we suffer a global ecological collapse, this other stuff you’re constantly talking about really isn’t going to matter—that is, if it mattered in the first place. When ISIS kills 200 people in an attack, you don’t just report that a bunch of people died without examining the cause or talking about responses. But when a typhoon triggered by climate change kills 7,000, suddenly it’s just a random event, an “act of God” that nobody could have predicted or prevented. Having an appropriate caution about whether climate change caused any particular disaster should not prevent us from drawing the very real links between more carbon emissions and more natural disasters—and sometimes there’s just no other explanation.

It means demanding fact-checks immediately, not as some kind of extra commentary that happens after the debate, but as something the moderator says right then and there. (You have a staff, right? And they have Google access, right?) When a candidate says something that is blatantly, demonstrably false, they should receive a warning. After three warnings, their mic should be cut for that question. After ten, they should be kicked off the stage for the remainder of the debate. Donald Trump wouldn’t have lasted five minutes. But instead, they not only let him speak, they spent the next week repeating what he said in bold, exciting headlines. At least CNN finally realized that their headlines could actually fact-check Trump’s statements rather than just repeat them.

Above all, we will need to understand why people think the way they do, and learn to speak to them persuasively and truthfully but without elitism or condescension. This is one I know I’m not very good at myself; sometimes I get so frustrated with people who think the Earth is 6,000 years old (over 40% of Americans) or don’t believe in climate change (35% don’t think it is happening at all, another 30% don’t think it’s a big deal) that I come off as personally insulting them—and of course from that point forward they turn off. But irrational beliefs are not proof of defective character, and we must make that clear to ourselves as well as to others. We must not say that people are stupid or bad; but we absolutely must say that they are wrong. We must also remember that despite our best efforts, some amount of reactance will be inevitable; people simply don’t like having their beliefs challenged.

Yet even all this is probably not enough. Many people don’t watch mainstream media, or don’t believe it when they do (not without reason). Many people won’t even engage with friends or family members who challenge their political views, and will defriend or even disown them. We need some means of reaching these people too, and the hardest part may be simply getting them to listen to us in the first place. Perhaps we need more grassroots action—more protest marches, or even activists going door to door like Jehovah’s Witnesses. Perhaps we need to establish new media outlets that will be as widely accessible but held to a higher standard.

But we must find a way–and we have little time to waste.