JDN 2457541

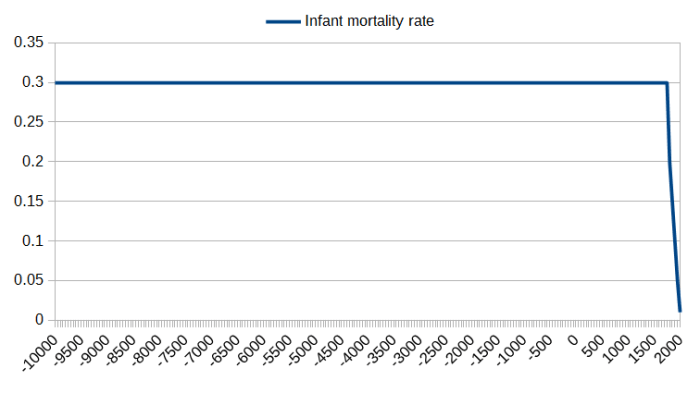

In a post last week I presented some of the overwhelming evidence that society has been getting better over time, particularly since the start of the Industrial Revolution. I focused mainly on infant mortality rates—babies not dying—but there are lots of other measures you could use as well. Despite popular belief, poverty is rapidly declining, and is now the lowest it’s ever been. War is rapidly declining. Crime is rapidly declining in First World countries, and to the best of our knowledge crime rates are stable worldwide. Public health is rapidly improving. Lifespans are getting longer. And so on, and so on. It’s not quite true to say that every indicator of human progress is on an upward trend, but the vast majority of really important indicators are.

Moreover, there is every reason to believe that this great progress is largely the result of what we call “civilization”, even Western civilization: Stable, centralized governments, strong national defense, representative democracy, free markets, openness to global trade, investment in infrastructure, science and technology, secularism, a culture that values innovation, and freedom of speech and the press. We did not get here by Marxism, nor agragrian socialism, nor primitivism, nor anarcho-capitalism. We did not get here by fascism, nor theocracy, nor monarchy. This progress was built by the center-left welfare state, “social democracy”, “modified capitalism”, the system where free, open markets are coupled with a strong democratic government to protect and steer them.

This fact is basically beyond dispute; the evidence is overwhelming. The serious debate in development economics is over which parts of the Western welfare state are most conducive to raising human well-being, and which parts of the package are more optional. And even then, some things are fairly obvious: Stable government is clearly necessary, while speaking English is clearly optional.

Yet many people are resistant to this conclusion, or even offended by it, and I think I know why: They are confusing the results of civilization with the methods by which it was established.

The results of civilization are indisputably positive: Everything I just named above, especially babies not dying.

But the methods by which civilization was established are not; indeed, some of the greatest atrocities in human history are attributable at least in part to attempts to “spread civilization” to “primitive” or “savage” people.

It is therefore vital to distinguish between the result, civilization, and the processes by which it was effected, such as colonialism and imperialism.

First, it’s important not to overstate the link between civilization and colonialism.

We tend to associate colonialism and imperialism with White people from Western European cultures conquering other people in other cultures; but in fact colonialism and imperialism are basically universal to any human culture that attains sufficient size and centralization. India engaged in colonialism, Persia engaged in imperialism, China engaged in imperialism, the Mongols were of course major imperialists, and don’t forget the Ottoman Empire; and did you realize that Tibet and Mali were at one time imperialists as well? And of course there are a whole bunch of empires you’ve probably never heard of, like the Parthians and the Ghaznavids and the Ummayyads. Even many of the people we’re accustoming to thinking of as innocent victims of colonialism were themselves imperialists—the Aztecs certainly were (they even sold people into slavery and used them for human sacrifice!), as were the Pequot, and the Iroquois may not have outright conquered anyone but were definitely at least “soft imperialists” the way that the US is today, spreading their influence around and using economic and sometimes military pressure to absorb other cultures into their own.

Of course, those were all civilizations, at least in the broadest sense of the word; but before that, it’s not that there wasn’t violence, it just wasn’t organized enough to be worthy of being called “imperialism”. The more general concept of intertribal warfare is a human universal, and some hunter-gatherer tribes actually engage in an essentially constant state of warfare we call “endemic warfare”. People have been grouping together to kill other people they perceived as different for at least as long as there have been people to do so.

This is of course not to excuse what European colonial powers did when they set up bases on other continents and exploited, enslaved, or even murdered the indigenous population. And the absolute numbers of people enslaved or killed are typically larger under European colonialism, mainly because European cultures became so powerful and conquered almost the entire world. Even if European societies were not uniquely predisposed to be violent (and I see no evidence to say that they were—humans are pretty much humans), they were more successful in their violent conquering, and so more people suffered and died. It’s also a first-mover effect: If the Ming Dynasty had supported Zheng He more in his colonial ambitions, I’d probably be writing this post in Mandarin and reflecting on why Asian cultures have engaged in so much colonial oppression.

While there is a deeply condescending paternalism (and often post-hoc rationalization of your own self-interested exploitation) involved in saying that you are conquering other people in order to civilize them, humans are also perfectly capable of committing atrocities for far less noble-sounding motives. There are holy wars such as the Crusades and ethnic genocides like in Rwanda, and the Arab slave trade was purely for profit and didn’t even have the pretense of civilizing people (not that the Atlantic slave trade was ever really about that anyway).

Indeed, I think it’s important to distinguish between colonialists who really did make some effort at civilizing the populations they conquered (like Britain, and also the Mongols actually) and those that clearly were just using that as an excuse to rape and pillage (like Spain and Portugal). This is similar to but not quite the same thing as the distinction between settler colonialism, where you send colonists to live there and build up the country, and exploitation colonialism, where you send military forces to take control of the existing population and exploit them to get their resources. Countries that experienced settler colonialism (such as the US and Australia) have fared a lot better in the long run than countries that experienced exploitation colonialism (such as Haiti and Zimbabwe).

The worst consequences of colonialism weren’t even really anyone’s fault, actually. The reason something like 98% of all Native Americans died as a result of European colonization was not that Europeans killed them—they did kill thousands of course, and I hope it goes without saying that that’s terrible, but it was a small fraction of the total deaths. The reason such a huge number died and whole cultures were depopulated was disease, and the inability of medical technology in any culture at that time to handle such a catastrophic plague. The primary cause was therefore accidental, and not really foreseeable given the state of scientific knowledge at the time. (I therefore think it’s wrong to consider it genocide—maybe democide.) Indeed, what really would have saved these people would be if Europe had advanced even faster into industrial capitalism and modern science, or else waited to colonize until they had; and then they could have distributed vaccines and antibiotics when they arrived. (Of course, there is evidence that a few European colonists used the diseases intentionally as biological weapons, which no amount of vaccine technology would prevent—and that is indeed genocide. But again, this was a small fraction of the total deaths.)

However, even with all those caveats, I hope we can all agree that colonialism and imperialism were morally wrong. No nation has the right to invade and conquer other nations; no one has the right to enslave people; no one has the right to kill people based on their culture or ethnicity.

My point is that it is entirely possible to recognize that and still appreciate that Western civilization has dramatically improved the standard of human life over the last few centuries. It simply doesn’t follow from the fact that British government and culture were more advanced and pluralistic that British soldiers can just go around taking over other people’s countries and planting their own flag (follow the link if you need some comic relief from this dark topic). That was the moral failing of colonialism; not that they thought their society was better—for in many ways it was—but that they thought that gave them the right to terrorize, slaughter, enslave, and conquer people.

Indeed, the “justification” of colonialism is a lot like that bizarre pseudo-utilitarianism I mentioned in my post on torture, where the mere presence of some benefit is taken to justify any possible action toward achieving that benefit. No, that’s not how morality works. You can’t justify unlimited evil by any good—it has to be a greater good, as in actually greater.

So let’s suppose that you do find yourself encountering another culture which is clearly more primitive than yours; their inferior technology results in them living in poverty and having very high rates of disease and death, especially among infants and children. What, if anything, are you justified in doing to intervene to improve their condition?

One idea would be to hold to the Prime Directive: No intervention, no sir, not ever. This is clearly what Gene Roddenberry thought of imperialism, hence why he built it into the Federation’s core principles.

But does that really make sense? Even as Star Trek shows progressed, the writers kept coming up with situations where the Prime Directive really seemed like it should have an exception, and sometimes decided that the honorable crew of Enterprise or Voyager really should intervene in this more primitive society to save them from some terrible fate. And I hope I’m not committing a Fictional Evidence Fallacy when I say that if your fictional universe specifically designed not to let that happen makes that happen, well… maybe it’s something we should be considering.

What if people are dying of a terrible disease that you could easily cure? Should you really deny them access to your medicine to avoid intervening in their society?

What if the primitive culture is ruled by a horrible tyrant that you could easily depose with little or no bloodshed? Should you let him continue to rule with an iron fist?

What if the natives are engaged in slavery, or even their own brand of imperialism against other indigenous cultures? Can you fight imperialism with imperialism?

And then we have to ask, does it really matter whether their babies are being murdered by the tyrant or simply dying from malnutrition and infection? The babies are just as dead, aren’t they? Even if we say that being murdered by a tyrant is worse than dying of malnutrition, it can’t be that much worse, can it? Surely 10 babies dying of malnutrition is at least as bad as 1 baby being murdered?

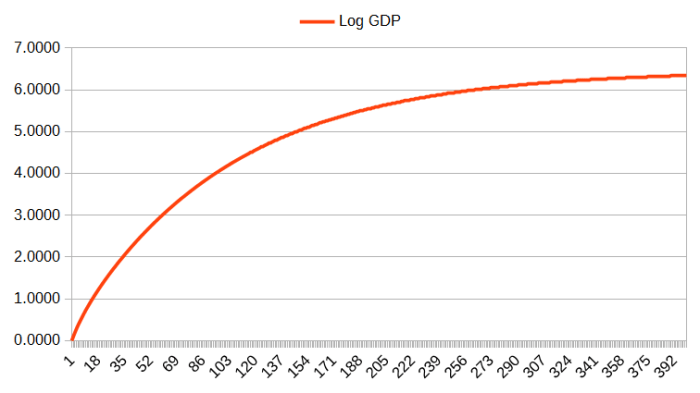

But then it begins to seem like we have a duty to intervene, and moreover a duty that applies in almost every circumstance! If you are on opposite sides of the technology threshold where infant mortality drops from 30% to 1%, how can you justify not intervening?

I think the best answer here is to keep in mind the very large costs of intervention as well as the potentially large benefits. The answer sounds simple, but is actually perhaps the hardest possible answer to apply in practice: You must do a cost-benefit analysis. Furthermore, you must do it well. We can’t demand perfection, but it must actually be a serious good-faith effort to predict the consequences of different intervention policies.

We know that people tend to resist most outside interventions, especially if you have the intention of toppling their leaders (even if they are indeed tyrannical). Even the simple act of offering people vaccines could be met with resistance, as the native people might think you are poisoning them or somehow trying to control them. But in general, opening contact with with gifts and trade is almost certainly going to trigger less hostility and therefore be more effective than going in guns blazing.

If you do use military force, it must be targeted at the particular leaders who are most harmful, and it must be designed to achieve swift, decisive victory with minimal collateral damage. (Basically I’m talking about just war theory.) If you really have such an advanced civilization, show it by exhibiting total technological dominance and minimizing the number of innocent people you kill. The NATO interventions in Kosovo and Libya mostly got this right. The Vietnam War and Iraq War got it totally wrong.

As you change their society, you should be prepared to bear most of the cost of transition; you are, after all, much richer than they are, and also the ones responsible for effecting the transition. You should not expect to see short-term gains for your own civilization, only long-term gains once their culture has advanced to a level near your own. You can’t bear all the costs of course—transition is just painful, no matter what you do—but at least the fungible economic costs should be borne by you, not by the native population. Examples of doing this wrong include basically all the standard examples of exploitation colonialism: Africa, the Caribbean, South America. Examples of doing this right include West Germany and Japan after WW2, and South Korea after the Korean War—which is to say, the greatest economic successes in the history of the human race. This was us winning development, humanity. Do this again everywhere and we will have not only ended world hunger, but achieved global prosperity.

What happens if we apply these principles to real-world colonialism? It does not fare well. Nor should it, as we’ve already established that most if not all real-world colonialism was morally wrong.

15th and 16th century colonialism fail immediately; they offer no benefit to speak of. Europe’s technological superiority was enough to give them gunpowder but not enough to drop their infant mortality rate. Maybe life was better in 16th century Spain than it was in the Aztec Empire, but honestly not by all that much; and life in the Iroquois Confederacy was in many ways better than life in 15th century England. (Though maybe that justifies some Iroquois imperialism, at least their “soft imperialism”?)

If these principles did justify any real-world imperialism—and I am not convinced that it does—it would only be much later imperialism, like the British Empire in the 19th and 20th century. And even then, it’s not clear that the talk of “civilizing” people and “the White Man’s Burden” was much more than rationalization, an attempt to give a humanitarian justification for what were really acts of self-interested economic exploitation. Even though India and South Africa are probably better off now than they were when the British first took them over, it’s not at all clear that this was really the goal of the British government so much as a side effect, and there are a lot of things the British could have done differently that would obviously have made them better off still—you know, like not implementing the precursors to apartheid, or making India a parliamentary democracy immediately instead of starting with the Raj and only conceding to democracy after decades of protest. What actually happened doesn’t exactly look like Britain cared nothing for actually improving the lives of people in India and South Africa (they did build a lot of schools and railroads, and sought to undermine slavery and the caste system), but it also doesn’t look like that was their only goal; it was more like one goal among several which also included the strategic and economic interests of Britain. It isn’t enough that Britain was a better society or even that they made South Africa and India better societies than they were; if the goal wasn’t really about making people’s lives better where you are intervening, it’s clearly not justified intervention.

And that’s the relatively beneficent imperialism; the really horrific imperialists throughout history made only the barest pretense of spreading civilization and were clearly interested in nothing more than maximizing their own wealth and power. This is probably why we get things like the Prime Directive; we saw how bad it can get, and overreacted a little by saying that intervening in other cultures is always, always wrong, no matter what. It was only a slight overreaction—intervening in other cultures is usually wrong, and almost all historical examples of it were wrong—but it is still an overreaction. There are exceptional cases where intervening in another culture can be not only morally right but obligatory.

Indeed, one underappreciated consequence of colonialism and imperialism is that they have triggered a backlash against real good-faith efforts toward economic development. People in Africa, Asia, and Latin America see economists from the US and the UK (and most of the world’s top economists are in fact educated in the US or the UK) come in and tell them that they need to do this and that to restructure their society for greater prosperity, and they understandably ask: “Why should I trust you this time?” The last two or four or seven batches of people coming from the US and Europe to intervene in their countries exploited them or worse, so why is this time any different?

It is different, of course; UNDP is not the East India Company, not by a longshot. Even for all their faults, the IMF isn’t the East India Company either. Indeed, while these people largely come from the same places as the imperialists, and may be descended from them, they are in fact completely different people, and moral responsibility does not inherit across generations. While the suspicion is understandable, it is ultimately unjustified; whatever happened hundreds of years ago, this time most of us really are trying to help—and it’s working.