Post 237: May 6 JDN 2458245

If you’ve been following the news surrounding the recent terrorist attack in Toronto, you may have encountered the word “incel” for the first time via articles in NPR, Vox, USA Today, or other sources linking the attack to the incel community.

If this was indeed your first exposure to the concept of “incel”, I think you are getting a distorted picture of their community, which is actually a surprisingly large Internet subculture. Finding out about incel this way would be like finding out about Islam from 9/11. (Actually, I’m fairly sure a lot of Americans did learn that way, which is awful.) The incel community is remarkably large one—hundreds of thousands of members at least, and quite likely millions.

While a large proportion subscribe to a toxic and misogynistic ideology, a similarly large proportion do not; while the ideology has contributed to terrorism and other violence, the vast majority of members of the community are not violent.

Note that the latter sentence is also entirely true of Islam. So if you are sympathetic toward Muslims and want to protect them from abuse and misunderstanding, I maintain that you should want to do the same for incels, and for basically the same reasons.

I want to make something abundantly clear at the outset:

This attack was terrorism. I am in no way excusing or defending the use of terrorism. Once someone crosses the line and starts attacking random civilians, I don’t care what their grievances were; the best response to their behavior involves snipers on rooftops. I frankly don’t even understand the risks police are willing to take in order to capture these people alive—especially considering how trigger-happy they are when it comes to random Black men. If you start shooting (or bombing, or crashing vehicles into) civilians, the police should shoot you. It’s that simple.

I do not want to evoke sympathy for incel-motivated terrorism. I want to evoke sympathy for the hundreds of thousands of incels who would never support terrorism and are now being publicly demonized.

I also want to make it clear that I am not throwing in my hat with the likes of Robin Hanson (who is also well-known as a behavioral economist, blogger, science fiction fan, Less Wrong devotee, and techno-utopian—so I feel a particular need to clarify my differences with him) when he defends something he calls in purposefully cold language “redistribution of sex” (that one is from right after the attack, but he has done this before, in previous blog posts).

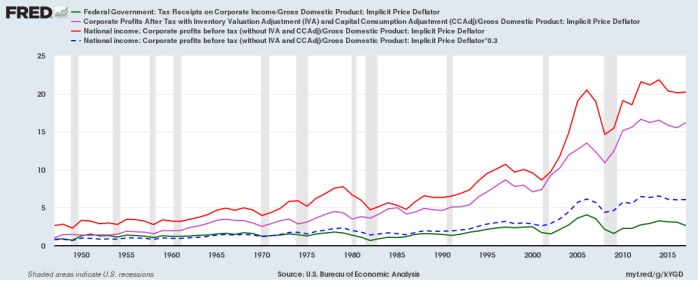

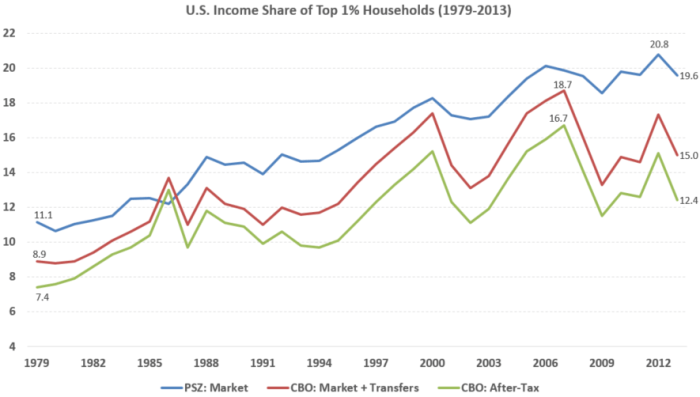

Hanson has drunk Robert Nozick‘s Kool-Aid, and thinks that redistribution of wealth via taxation is morally equivalent to theft or even slavery. He is fond of making comparisons between redistribution of wealth and other forms of “redistribution” that obviously would be tantamount to theft and slavery, and asking “What’s the difference?” when in fact the difference is glaringly obvious to everyone but him. He is also fond of saying that “inequality between households within a nation” is a small portion of inequality, and then wondering aloud why we make such a big deal out of it. The answer here is also quite obvious: First of all, it’s not that small a portion of inequality—it’s a third of global income inequality by most measures, it’s increasing while across-nation inequality is decreasing, and the absolute magnitude of within-nation inequality is staggering: there are households with incomes over one million times that of other households within the same nation. (Where are the people who have had sex one hundred billion times, let alone the ones who had sex forty billion times in one year? Because here’s the man who has one hundred billion dollars and made almost $40 billion in one year.) Second, within-nation inequality is extremely simple to fix by public policy; just change a few numbers in the tax code—in fact, just change them back to what they were in the 1950s. Cross-national inequality is much more complicated (though I believe it can be solved, eventually) and some forms of what he’s calling “inequality” (like “inequality across periods of human history” or “inequality of innate talent”) don’t seem amenable to correction under any conceivable circumstances.

Hanson has lots of just-so stories about the evolutionary psychology of why “we don’t care” about cross-national inequality (gee, I thought maybe devoting my career to it was a pretty good signal otherwise?) or inequality in access to sex (which is thousands of times smaller than income inequality), but no clear policy suggestions for how these other forms of inequality could be in any way addressed. This whole idea of “redistribution of sex”; what does that mean, exactly? Legalized or even subsidized prostitution or sex robots would be one thing; I can see pros and cons there at least. But without clarification, it sounds like he’s endorsing the most extremist misogynist incels who think that women should be rightfully compelled to have sex with sexually frustrated men—which would be quite literally state-sanctioned rape. I think really Hanson isn’t all that interested in incels, and just wants to make fun of silly “socialists” who would dare suppose that maybe Jeff Bezos doesn’t need his 120 billion dollars as badly as some of the starving children in Africa could benefit from them, or that maybe having a tax system similar to Sweden or Denmark (which consistently rate as some of the happiest, most prosperous nations on Earth) sounds like a good idea. He takes things that are obviously much worse than redistributive taxation, and compares them to redistributive taxation to make taxation seem worse than it is.

No, I do not support “redistribution of sex”. I might be able to support legalized prostitution, but I’m concerned about the empirical data suggesting that legalized prostitution correlates with increased human sex trafficking. I think I would also support legalized sex robots, but for reasons that will become clear shortly, I strongly suspect they would do little to solve the problem, even if they weren’t ridiculously expensive. Beyond that, I’ve said enough about Hanson; Lawyers, Guns & Money nicely skewers Hanson’s argument, so I’ll not bother with it any further.

Instead, I want to talk about the average incel, one of hundreds of thousands if not millions of men who feels cast aside by society because he is socially awkward and can’t get laid. I want to talk about him because I used to be very much like him (though I never specifically identified as “incel”), and I want to talk about him because I think that he is genuinely suffering and needs help.

There is a moderate wing of the incel community, just as there is a moderate wing of the Muslim community. The moderate wing of incels is represented by sites like Love-Shy.com that try to reach out to people (mostly, but not exclusively young heterosexual men) who are lonely and sexually frustrated and often suffering from social anxiety or other mood disorders. Though they can be casually sexist (particularly when it comes to stereotypes about differences between men and women), they are not virulently misogynistic and they would never support violence. Moreover, they provide a valuable service in offering social support to men who otherwise feel ostracized by society. I disagree with a lot of things these groups say, but they are providing valuable benefits to their members and aren’t hurting anyone else. Taking out your anger against incel terrorists on Love-Shy.com is like painting graffiti on a mosque in response to 9/11 (which, of course, people did).

To some extent, I can even understand the more misogynistic (but still non-violent) wings of the incel community. I don’t want to defend their misogyny, but I can sort of understand where it might come from.

You see, men in our society (and most societies) are taught from a very young age that their moral worth as human beings is based primarily on one thing in particular: Sexual prowess. If you are having a lot of sex with a lot of women, you are a good and worthy man. If you are not, you are broken and defective. (Donald Trump has clearly internalized this narrative quite thoroughly—as have a shockingly large number of his supporters.)

This narrative is so strong and so universal, in fact, that I wouldn’t be surprised if it has a genetic component. It actually makes sense as a matter of evolutionary psychology than males would evolve to think this way; in an evolutionary sense it’s true that a male’s ultimate worth—that is, fitness, the one thing natural selection cares about—is defined by mating with a maximal number of females. But even if it has a genetic component, there is enough variation in this belief that I am confident that social norms can exaggerate or suppress it. One thing I can’t stand about popular accounts of evolutionary psychology is how they leap from “plausible evolutionary account” to “obviously genetic trait” all the way to “therefore impossible to change or compensate for”. My myopia and astigmatism are absolutely genetic; we can point to some of the specific genes. And yet my glasses compensate for them perfectly, and for a bit more money I could instead get LASIK surgery that would correct them permanently. Never think for a moment that “genetic” implies “immutable”.

Because of this powerful narrative, men who are sexually frustrated get treated like garbage by other men and even women. They feel ostracized and degraded. Often, they even feel worthless. If your worth as a human being is defined by how many women you have sex with, and you aren’t having sex with any, it follows that your worth is zero. No wonder, then, that so many become overcome with despair.

The incel community provides an opportunity to escape that despair. If you are told that you are not defective, but instead there is something wrong with society that keeps you down, you no longer have to feel worthless. It’s not that you don’t deserve to have sex, it’s that you’ve been denied what you deserve. When the only other narrative you’ve been given is that you are broken and worthless, I can see why “society is screwing you over” is an appealing counter-narrative. Indeed, it’s not even that far off from the truth.

The moderate wing of the incel community even offers some constructive solutions: They offer support to help men improve themselves, overcome their own social anxiety, and ultimately build fulfilling sexual relationships.

The extremist wing gets this all wrong: Instead of blaming the narrative that sex equals worth, they blame women—often, all women—for somehow colluding to deny them access to the sex they so justly deserve. They often link themselves to the “pick-up artist” community who try to manipulate women into having sex.

And then in the most extreme cases, they may even decide to turn their anger into violence.

But really I don’t think most of these men actually want sex at all, which is part of why I don’t think sex robots would be particularly effective.

Rather, to clarify: They want sex, as most of us do—but that’s not what they need. A simple lack of sex can be compensated reasonably well by pornography and masturbation. (Let me state this outright: Pornography and masturbation are fundamental human rights. Porn is free speech, and masturbation is part of the fundamental right of bodily autonomy. The fact that increased access to porn reduces incidence of sexual assault is nice, but secondary; porn is freedom.) Obviously it would be more satisfying to have a real sexual relationship, but with such substitutes available, a mere lack of sex does not cause suffering.

The need that these men are feeling is companionship. It is love. It is understanding. These are things that can’t be replaced, even partially, by sex robots or Internet porn.

Why do they conflate the two? Again, because society has taught them to do so. This one is clearly cultural, as it varies quite considerably between nations; it’s not nearly as bad in Southern Europe for example.

In American society (and many, but not all others), men are taught three things: First, expression of any emotion except for possibly anger, and especially expression of affection, is inherently erotic. Second, emotional vulnerability jeopardizes masculinity. Third, erotic expression must be only between men and women in a heterosexual relationship.

In principle, it might be enough to simply drop the third proposition: This is essentially what happens in the LGBT community. Gay men still generally suffer from the suspicion that all emotional expression is erotic, but have long-since abandoned their fears of expressing eroticism with other men. Often they’ve also given up on trying to sustain norms of masculinity as well. So gay men can hug each other and cry in front of each other, for example, without breaking norms within the LGBT community; the sexual subtext is often still there, but it’s considered unproblematic. (Gay men typically aren’t even as concerned about sexual infidelity as straight men; over 40% of gay couples are to some degree polyamorous, compared to 5% of straight couples.) It may also be seen as a loss of masculinity, but this too is considered unproblematic in most cases. There is a notable exception, which is the substantial segment of gay men who pride themselves upon hypermasculinity (generally abbreviated “masc”); and indeed, within that subcommunity you often see a lot of the same toxic masculinity norms that are found in the society as large.

That is also what happened in Classical Greece and Rome, I think: These societies were certainly virulently misogynistic in their own way, but their willingness to accept erotic expression between men opened them to accepting certain kinds of emotional expression between men as well, as long as it was not perceived as a threat to masculinity per se.

But when all three of those norms are in place, men find that the only emotional outlet they are even permitted to have while remaining within socially normative masculinity is a woman who is a romantic partner. Family members are allowed certain minimal types of affection—you can hug your mom, as long as you don’t seem too eager—but there is only one person in the world that you are allowed to express genuine emotional vulnerability toward, and that is your girlfriend. If you don’t have one? Get one. If you can’t get one? Well, sorry, pal, you’re just out of luck. Deal with it, or you’re not a real man.

But really what I’d like to get rid of is the first two propositions: Emotional expression should not be considered inherently sexual. Expressing emotional vulnerability should not be taken as a capitulation of your masculinity—and if I really had my druthers, the whole idea of “masculinity” would disappear or become irrelevant. This is the way that society is actually holding incels down: Not by denying them access to sex—the right to refuse sex is also a fundamental human right—but by denying them access to emotional expression and treating them like garbage because they are unable to have sex.

My sense is that what most incels are really feeling is not a dearth of sexual expression; it’s a dearth of emotional expression. But precisely because social norms have forced them into getting the two from the same place, they have conflated them. Further evidence in favor of this proposition? A substantial proportion of men who hire prostitutes spend a lot of the time they paid for simply talking.

I think what most of these men really need is psychotherapy. I’m not saying that to disparage them; I myself am a regular consumer of psychotherapy, which is one of the most cost-effective medical interventions known to humanity. I feel a need to clarify this because there is so much stigma on mental illness that saying someone is mentally ill and needs therapy can be taken as an insult; but I literally mean that a lot of these men are mentally ill and need therapy. Many of them exhibit significant signs of social anxiety, depression, or bipolar disorder.

Even for those who aren’t outright mentally ill, psychotherapy might be able to help them sort out some of these toxic narratives they’ve been fed by society, get them to think a little more carefully about what it means to be a good man and whether the “man” part is even so important. A good therapist could tease out the fabric of their tangled cognition and point out that when they say they want sex, it really sounds like they want self-worth, and when they say they want a girlfriend it really sounds like they want someone to talk to.

Such a solution won’t work on everyone, and it won’t work overnight on anyone. But the incel community did not emerge from a vacuum; it was catalyzed by a great deal of genuine suffering. Remove some of that suffering, and we might just undermine the most dangerous parts of the incel community and prevent at least some future violence.

No one owes sex to anyone. But maybe we do, as a society, owe these men a little more sympathy?