JDN 2457075 EST 14:46.

I am back on Eastern Time once again, because we just finished our 3600-km road trek from Long Beach to Ann Arbor. I seem to move an awful lot; this makes me a bit like Schumpeter, who moved an average of every two years his whole adult life. Schumpeter and I have much in common, in fact, though I have no particular interest in horses.

Today’s topic is the sunk-cost fallacy, which was particularly salient as I had to box up all my things for the move. There were many items that I ended up having to throw away because it wasn’t worth moving them—but this was always painful, because I couldn’t help but think of all the work or money I had put into them. I threw away craft projects I had spent hours working on and collections of bottlecaps I had gathered over years—because I couldn’t think of when I’d use them, and ultimately the question isn’t how hard they were to make in the past, it’s what they’ll be useful for in the future. But each time it hurt, like I was giving up a little part of myself.

That’s the sunk-cost fallacy in a nutshell: Instead of considering whether it will be useful to us later and thus worth having around, we naturally tend to consider the effort that went into getting it. Instead of making our decisions based on the future, we make them based on the past.

Come to think of it, the entire Marxist labor theory of value is basically one gigantic sunk-cost fallacy: Instead of caring about the usefulness of a product—the mainstream utility theory of value—we are supposed to care about the labor that went into making it. To see why this is wrong, imagine someone spends 10,000 hours carving meaningless symbols into a rock, and someone else spends 10 minutes working with chemicals but somehow figures out how to cure pancreatic cancer. Which one would you pay more for—particularly if you had pancreatic cancer?

This is one of the most common irrational behaviors humans do, and it’s worth considering why that might be. Most people commit the sunk-cost fallacy on a daily basis, and even those of us who are aware of it will still fall into it if we aren’t careful.

This often seems to come from a fear of being wasteful; I don’t know of any data on this, but my hunch is that the more environmentalist you are, the more often you tend to run into the sunk-cost fallacy. You feel particularly bad wasting things when you are conscious of the damage that waste does to our planetary ecosystem. (Which is not to say that you should not be environmentalist; on the contrary, most of us should be a great deal more environmentalist than we are. The negative externalities of environmental degradation are almost unimaginably enormous—climate change already kills 150,000 people every year and is projected to kill tens if not hundreds of millions people over the 21st century.)

I think sunk-cost fallacy is involved in a lot of labor regulations as well. Most countries have employment protection legislation that makes it difficult to fire people for various reasons, ranging from the basically reasonable (discrimination against women and racial minorities) to the totally absurd (in some countries you can’t even fire people for being incompetent). These sorts of regulations are often quite popular, because people really don’t like the idea of losing their jobs. When faced with the possibility of losing your job, you should be thinking about what your future options are; but many people spend a lot of time thinking about the past effort they put into this one. I think there is also some endowment effect and loss aversion at work as well: You value your job more simply because you already have it, so you don’t want to lose it even for something better.

Yet these regulations are widely regarded by economists as inefficient; and for once I am inclined to agree. While I certainly don’t want people being fired frivolously or for discriminatory reasons, sometimes companies really do need to lay off workers because there simply isn’t enough demand for their products. When a factory closes down, we think about the jobs that are lost—but we don’t think about the better jobs they can now do instead.

I favor a system like what they have in Denmark (I’m popularizing a hashtag about this sort of thing: #Scandinaviaisbetter): We don’t try to protect your job, we try to protect you. Instead of regulations that make it hard to fire people, Denmark has a generous unemployment insurance system, strong social welfare policies, and active labor market policies that help people retrain and find new and better jobs. One thing I think Denmark might want to consider is restrictions on cyclical layoffs—in a recession there is pressure to lay off workers, but that can create a vicious cycle that makes recessions worse. Denmark was hit considerably harder by the Great Recession than France, for example; where France’s unemployment rose from 7.5% to 9.6%, Denmark’s rose from an astonishing 3.1% all the way up to 7.6%.

Then again, sometimes what looks like a sunk-cost fallacy actually isn’t—and I think this gives us insight into how we might have evolved such an apparently silly heuristic in the first place.

Why would you care about what you did in the past when deciding what to do in the future? Well there’s one reason in particular: Credible commitment. There are many cases in life where you’d like to be able to plan to do something in the future, but when the time comes to actually do it you’ll be tempted not to follow through.

This sort of thing happens all the time: When you take out a loan, you plan to pay it back—but when you need to actually make payments it sure would be nice if you didn’t have to. If you’re trying to slim down, you go on a diet—but doesn’t that cookie look delicious? You know you should quit smoking for your health—but what’s one more cigarette, really? When you get married, you promise to be faithful—but then sometimes someone else comes along who seems so enticing! Your term paper is due in two weeks, so you really should get working on it—but your friends are going out for drinks tonight, why not start the paper tomorrow?

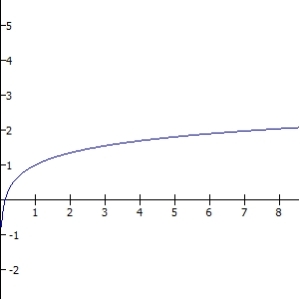

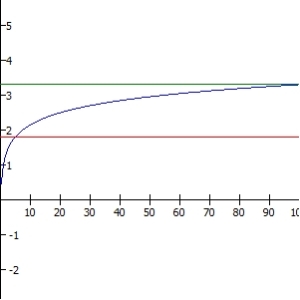

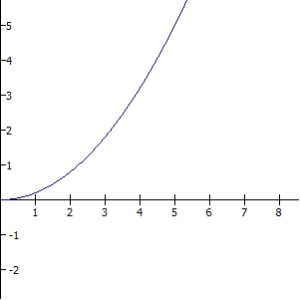

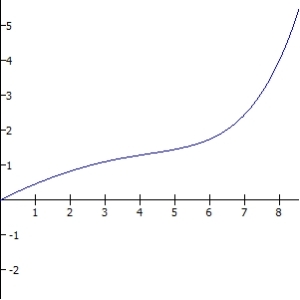

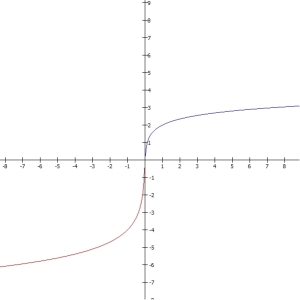

Our true long-term interests are often misaligned with our short-term temptations. This often happens because of hyperbolic discounting, which is a bit technical; but the basic idea is that you tend to rate the importance of an event in inverse proportion to its distance in time. That turns out to be irrational, because as you get closer to the event, your valuations will change disproportionately. The optimal rational choice would be exponential discounting, where you value each successive moment a fixed percentage less than the last—since that percentage doesn’t change, your valuations will always stay in line with one another. But basically nobody really uses exponential discounting in real life.

We can see this vividly in experiments: If we ask people whether they would you rather receive $100 today, or $110 a week from now, they often go with $100 today. But if you ask them whether they would rather receive $100 in 52 weeks or $110 in 53 weeks, almost everyone chooses the $110. The value of a week apparently depends on how far away it is! (The $110 is clearly the rational choice by the way. Discounting 10% per week makes no sense at all—unless you literally believe that $1,000 today is as good as $140,000 a year from now.)

To solve this problem, it can be advantageous to make commitments—either enforced by direct measures such as legal penalties, or even simply by making promises that we feel guilty breaking. That’s why cold turkey is often the most effective way to quit a drug. Physiologically that makes no sense, because gradual cessation clearly does reduce withdrawal symptoms. But psychologically it does, because cold turkey allows you to make a hardline commitment to never again touch the stuff. The majority of successful smokers report using cold turkey, though there is still ongoing research on whether properly-orchestrated gradual reduction can be more effective. Likewise, vague notions like “I’ll eat better and exercise more” are virtually useless, while specific prescriptions like “I will do 20 minutes of exercise every day and stop eating red meat” are much more effective—the latter allows you to make a promise to yourself that can be broken, and since you feel bad breaking it you are motivated to keep it.

In the presence of such commitments, the past does matter, at least insofar as you made commitments to yourself or others in the past. If you promised never to smoke another cigarette, or never to cheat on your wife, or never to eat meat again, you actually have a good reason—and a good chance—to never do those things. This is easy to confuse with a sunk cost; when you think about the 20 years you’ve been married or the 10 years you’ve been vegetarian, you might be thinking of the sunk cost you’ve incurred over that time, or you might be thinking of the promises you’ve made and kept to yourself and others. In the former case you are irrationally committing a sunk-cost fallacy; in the latter you are rationally upholding a credible commitment.

This is most likely why we evolved in such a way as to commit sunk-cost fallacies. The ability to enforce commitments on ourselves and others was so important that it was worth it to overcompensate and sometimes let us care about sunk costs. Because commitments and sunk costs are often difficult to distinguish, it would have been more costly to evolve better ways of distinguish them than it was to simply make the mistake.

Perhaps people who are outraged by being laid off aren’t actually committing a sunk-cost fallacy at all; perhaps they are instead assuming the existence of a commitment where none exists. “I gave this company 20 good years, and now they’re getting rid of me?” But the truth is, you gave the company nothing. They never committed to keeping you (unless they signed a contract, but that’s different; if they are violating a contract, of course they should be penalized for that). They made you a trade, and when that trade ceases to be advantageous they will stop making it. Corporations don’t think of themselves as having any moral obligations whatsoever; they exist only to make profit. It is certainly debatable whether it was a good idea to set up corporations in this way; but unless and until we change that system it is important to keep it in mind. You will almost never see a corporation do something out of kindness or moral obligation; that’s simply not how corporations work. At best, they do nice things to enhance their brand reputation (Starbucks, Whole Foods, Microsoft, Disney, Costco). Some don’t even bother doing that, letting people hate as long as they continue to buy (Walmart, BP, DeBeers). Actually the former model seems to be more successful lately, which bodes well for the future; but be careful to recognize that few if any of these corporations are genuinely doing it out of the goodness of their hearts. Human beings are often altruistic; corporations are specifically designed not to be.

And there were some things I did promise myself I would keep—like old photos and notebooks that I want to keep as memories—so those went in boxes. Other things were obviously still useful—clothes, furniture, books. But for the rest? It was painful, but I thought about what I could realistically use them for, and if I couldn’t think of anything, they went into the trash.