JDN 2457468

One thing that really stuck out to me about the analysis of the outcome of the Michigan primary elections was that people kept talking about trade; when Bernie Sanders, a center-left social democrat, and Donald Trump, a far-right populist nationalist (and maybe even crypto-fascist) are the winners, something strange is at work. The one common element that the two victors seemed to have was their opposition to free trade agreements. And while people give many reasons to support Trump, many quite baffling, his staunch protectionism is one of the stronger voices. While Sanders is not as staunchly protectionist, he definitely has opposed many free-trade agreements.

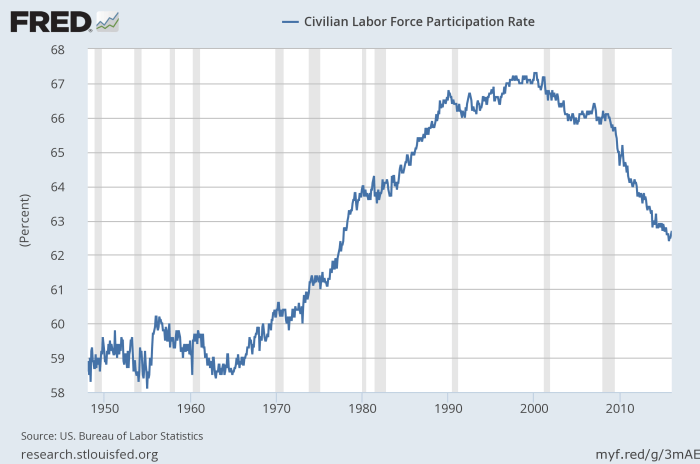

Most of the American middle class feels as though they are running in place, working as hard as they can to stay where they are and never moving forward. The income statistics back them up on this; as you can see in this graph from FRED, real median household income in the US is actually lower than it was a decade ago; it never really did recover from the Second Depression:

As I talk to people about why they think this is, one of the biggest reasons they always give is some variant of “We keep sending our jobs to China.” There is this deep-seated intuition most Americans seem to have that the degradation of the middle class is the result of trade globalization. Bernie Sanders speaks about ending this by changes in tax policy and stronger labor regulations (which actually makes some sense); Donald Trump speaks of ending this by keeping out all those dirty foreigners (which appeals to the worst in us); but ultimately, they both are working from the narrative that free trade is the problem.

But free trade is not the problem. Like almost all economists, I support free trade. Free trade agreements might be part of the problem—but that’s because a lot of free trade agreements aren’t really about free trade. Many trade agreements, especially the infamous TRIPS accord, were primarily about restricting trade—specifically on “intellectual property” goods like patented drugs and copyrighted books. They were about expanding the monopoly power of corporations over their products so that the monopoly applied not just to the United States, but indeed to the whole world. This is the opposite of free trade and everything that it stands for. The TPP was a mixed bag, with some genuinely free-trade provisions (removing tariffs on imported cars) and some awful anti-trade provisions (making patents on drugs even stronger).

Every product we buy as an import is another product we sell as an export. This is not quite true, as the US does run a trade deficit; but our trade deficit is small compared to our overall volume of trade (which is ludicrously huge). Total US exports for 2014, the last full year we’ve fully tabulated, were $3.306 trillion—roughly the entire budget of the federal government. Total US imports for 2014 were $3.578 trillion. This makes our trade deficit $272 billion, which is 7.6% of our imports, or about 1.5% of our GDP of $18.148 trillion. So to be more precise, every 100 products we buy as imports are 92 products we sell as exports.

If we stopped making all these imports, what would happen? Well, for one thing, millions of people in China would lose their jobs and fall back into poverty. But even if you’re just looking at the US specifically, there’s no reason to think that domestic production would increase nearly as much as the volume of trade was reduced, because the whole point of trade is that it’s more efficient than domestic production alone. It is actually generous to think that by switching to autarky we’d have even half the domestic production that we’re currently buying in imports. And then of course countries we export to would retaliate, and we’d lose all those exports. The net effect of cutting ourselves off from world trade would be a loss of about $1.5 trillion in GDP—average income would drop by 8%.

Now, to be fair, there are winners and losers. Offshoring of manufacturing does destroy the manufacturing jobs that are offshored; but at least when done properly, it also creates new jobs by improved efficiency. These two effects are about the same size, so the overall effect is a small decline in the overall number of US manufacturing jobs. It’s not nearly large enough to account for the collapsing middle class.

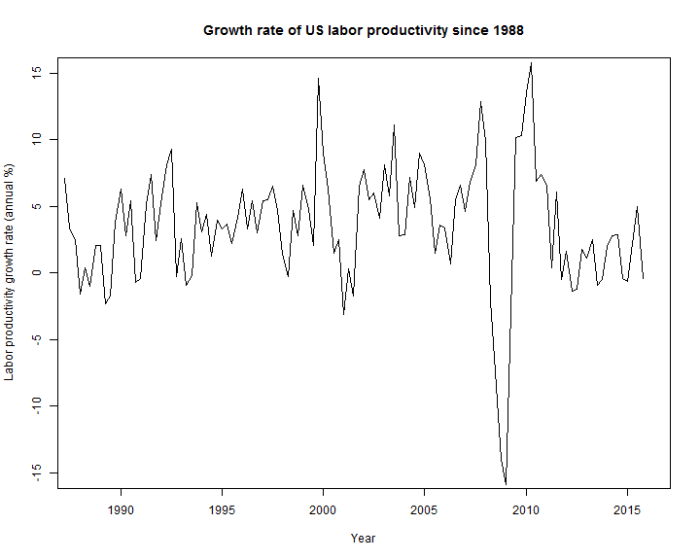

Globalization may be one contributor to rising inequality, as may changes in technology that make some workers (software programmers) wildly more productive as they make other workers (cashiers, machinists, and soon truck drivers) obsolete. But those of us who have looked carefully at the causes of rising income inequality know that this is at best a small part of what’s really going on.

The real cause is what Bernie Sanders is always on about: The 1%. Gains in income in the US for the last few decades (roughly as long as I’ve been alive) have been concentrated in a very small minority of the population—in fact, even 1% may be too coarse. Most of the income gains have actually gone to more like the top 0.5% or top 0.25%, and the most spectacular increases in income have all been concentrated in the top 0.01%.

The story that we’ve been told—I dare say sold—by the mainstream media (which is, lets face it, owned by a handful of corporations) is that new technology has made it so that anyone who works hard (or at least anyone who is talented and works hard and gets a bit lucky) can succeed or even excel in this new tech-driven economy.

I just gave up on a piece of drivel called Bold that was seriously trying to argue that anyone with a brilliant idea can become a billionaire if they just try hard enough. (It also seemed positively gleeful about the possibility of a cyberpunk dystopia in which corporations use mass surveillance on their customers and competitors—yes, seriously, this was portrayed as a good thing.) If you must read it, please, don’t give these people any more money. Find it in a library, or find a free ebook version, or something. Instead you should give money to the people who wrote the book I switched to, Raw Deal, whose authors actually understand what’s going on here (though I maintain that the book should in fact be called Uber Capitalism).

When you look at where all the money from the tech-driven “new economy” is going, it’s not to the people who actually make things run. A typical wage for a web developer is about $35 per hour, and that’s relatively good as far as entry-level tech jobs. A typical wage for a social media intern is about $11 per hour, which is probably less than what the minimum wage ought to be. The “sharing economy” doesn’t produce outstandingly high incomes for workers, just outstandingly high income risk because you aren’t given a full-time salary. Uber has claimed that its drivers earn $90,000 per year, but in fact their real take-home pay is about $25 per hour. A typical employee at Airbnb makes $28 per hour. If you do manage to find full-time hours at those rates, you can make a middle-class salary; but that’s a big “if”. “Sharing economy”? Robert Reich has aptly renamed it the “share the crumbs economy”.

So where’s all this money going? CEOs. The CEO of Uber has net wealth of $8 billion. The CEO of Airbnb has net wealth of $3.3 billion. But they are paupers compared to the true giants of the tech industry: Larry Page of Google has $36 billion. Jeff Bezos of Amazon has $49 billion. And of course who can forget Bill Gates, founder of Microsoft, and his mind-boggling $77 billion.

Can we seriously believe that this is because their ideas were so brilliant, or because they are so talented and skilled? Uber’s “brilliant” idea is just to monetize carpooling and automate linking people up. Airbnb’s “revolutionary” concept is an app to advertise your bed-and-breakfast. At least Google invented some very impressive search algorithms, Amazon created one of the most competitive product markets in the world, and Microsoft democratized business computing. Of course, none of these would be possible without the invention of the Internet by government and university projects.

As for what these CEOs do that is so skilled? At this point they basically don’t do… anything. Any real work they did was in the past, and now it’s all delegated to other people; they just rake in money because they own things. They can manage if they want, but most of them have figured out that the best CEOs do very little while CEOS who micromanage typically fail. While I can see some argument for the idea that working hard in the past could merit you owning capital in the future, I have a very hard time seeing how being very good at programming and marketing makes you deserve to have so much money you could buy a new Ferrari every day for the rest of your life.

That’s the heuristic I like to tell people, to help them see the absolutely enormous difference between a millionaire and a billionaire: A millionaire is someone who can buy a Ferrari. A billionaire is someone who can buy a new Ferrari every day for the rest of their life. A high double-digit billionaire like Bezos or Gates could buy a new Ferrari every hour for the rest of their life. (Do the math; a Ferrari is about $250,000. Remember that they get a return on capital typically between 5% and 15% per year. With $1 billion, you get $50 to $150 million just in interest and dividends every year, and $100 million is enough to buy 365 Ferraris. As long as you don’t have several very bad years in a row on your stocks, you can keep doing this more or less forever—and that’s with only $1 billion.)

Immigration and globalization are not what is killing the American middle class. Corporatization is what’s killing the American middle class. Specifically, the use of regulatory capture to enforce monopoly power and thereby appropriate almost all the gains of new technologies into into the hands of a few dozen billionaires. Typically this is achieved through intellectual property, since corporate-owned patents basically just are monopolistic regulatory capture.

Since 1984, US real GDP per capita rose from $28,416 to $46,405 (in 2005 dollars). In that same time period, real median household income only rose from $48,664 to $53,657 (in 2014 dollars). That means that the total amount of income per person in the US rose by 49 log points (63%), while the amount of income that a typical family received only rose 10 log points (10%). If median income had risen at the same rate as per-capita GDP (and if inequality remained constant, it would), it would now be over $79,000, instead of $53,657. That is, a typical family would have $25,000 more than they actually do. The poverty line for a family of 4 is $24,300; so if you’re a family of 4 or less, the billionaires owe you a poverty line. You should have three times the poverty line, and in fact you have only two—because they took the rest.

And let me be very clear: I mean took. I mean stole, in a very real sense. This is not wealth that they created by their brilliance and hard work. This is wealth that they expropriated by exploiting people and manipulating the system in their favor. There is no way that the top 1% deserves to have as much wealth as the bottom 95% combined. They may be talented; they may work hard; but they are not that talented, and they do not work that hard. You speak of “confiscation of wealth” and you mean income taxes? No, this is the confiscation of our nation’s wealth.

Those of us who voted for Bernie Sanders voted for someone who is trying to stop it.

Those of you who voted for Donald Trump? Congratulations on supporting someone who epitomizes it.