JDN 2457352

Our journey through the world of taxes continues. I’ve already talked about how taxes have upsides and downsides, as well as how taxes directly affect prices and “before-tax” prices are almost meaningless.

Now it’s time to get into something that even a lot of economists don’t quite seem to grasp, yet which turns out to be fundamental to what taxes truly are.

In the usual way of thinking, it works something like this: We have an economy, through which a bunch of money flows, and then the government comes in and takes some of that money in the form of taxes. They do this because they want to spend money on a variety of services, from military defense to public schools, and in order to afford doing that they need money, so they take in taxes.

This view is not simply wrong—it’s almost literally backwards. Money is not something the economy had that the government comes in and takes. Money is something that the government creates and then adds to the economy to make it function more efficiently. Taxes are not the government taking out money that they need to use; taxes are the government regulating the quantity of money in the system in order to stabilize its value. The government could spend as much money as they wanted without collecting a cent in taxes (not should, but could—it would be a bad idea, but definitely possible); taxes do not exist to fund the government, but to regulate the money supply.

Indeed—and this is the really vital and counter-intuitive point—without taxes, money would have no value.

There is an old myth of how money came into existence that involves bartering: People used to trade goods for other goods, and then people found that gold was particularly good for trading, and started using it for everything, and then eventually people started making paper notes to trade for gold, and voila, money was born.

In fact, such a “barter economy” has never been documented to exist. It probably did once or twice, just given the enormous variety of human cultures; but it was never widespread. Ancient economies were based on family sharing, gifts, and debts of honor.

It is true that gold and silver emerged as the first forms of money, “commodity money”, but they did not emerge endogenously out of trading that was already happening—they were created by the actions of governments. The real value of the gold or silver may have helped things along, but it was not the primary reason why people wanted to hold the money. Money has been based upon government for over 3000 years—the history of money and civilization as we know it. “Fiat money” is basically a redundancy; almost all money, even in a gold standard system, is ultimately fiat money.

The primary reason why people wanted the money was so that they could use it to pay taxes.

It’s really quite simple, actually.

When there is a rule imposed by the government that you will be punished if you don’t turn up on April 15 with at least $4,287 pieces of green paper marked “US Dollar”, you will try to acquire $4,287 pieces of green paper marked “US Dollar”. You will not care whether those notes are exchangeable for gold or silver; you will not care that they were printed by the government originally. Because you will be punished if you don’t come up with those pieces of paper, you will try to get some.

If someone else has some pieces of green paper marked “US Dollar”, and knows that you need them to avoid being punished on April 15, they will offer them to you—provided that you give them something they want in return. Perhaps it’s a favor you could do for them, or something you own that they’d like to have. You will be willing to make this exchange, in order to avoid being punished on April 15.

Thus, taxation gives money value, and allows purchases to occur.

Once you establish a monetary system, it becomes self-sustaining. If you know other people will accept money as payment, you are more willing to accept money as payment because you know that you can go spend it with those people. “Legal tender” also helps this process along—the government threatens to punish people who refuse to accept money as payment. In practice, however, this sort of law is rarely enforced, and doesn’t need to be, because taxation by itself is sufficient to form the basis of the monetary system.

It’s deeply ironic that people who complain about printing money often say we are “debasing” the currency; when you think carefully about what debasement was, it clearly shows that the value of money never really resided in the gold or silver itself. If a government can successfully extract revenue from its monetary system by changing the amount of gold or silver in each coin, then the value of those coins can’t be in the gold and silver—it has to be in the power of the government. You can’t make a profit by dividing a commodity into smaller pieces and then selling the pieces. (Okay, you sort of can, by buying in bulk and selling at retail. But that’s not what we’re talking about. You can’t make money by buying 100 50-gallon barrels of oil and then selling them as 125 40-gallon barrels of oil; it’s the same amount of oil.)

Similarly, the fact that there is such a thing as seigniorage—the value of currency in excess of its cost to create—shows that governments impart value to their money. Indeed, one of the reasons for debasement was to realign the value of coins with the value of the metals in the coins, which wouldn’t be necessary if those were simply by definition the same thing.

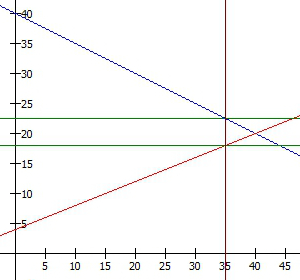

Taxation serves another important function in the monetary system, which is to regulate the supply of money. The government adds money to the economy by spending, and removes it by taxing; if they add more than they remove—a deficit—the money supply increases, while if they remove more than they add—a surplus—the money supply decreases. In order to maintain stable prices, you want the money supply to increase at approximately the rate of growth; for moderate inflation (which is probably better than actual price stability), you want the money supply to increase slightly faster than the rate of growth. Thus, in general we want the government deficit as a portion of GDP to be slightly larger than the growth rate of the economy. Thus, our current deficit of 2.8% of GDP is actually about where it should be, and we have no particular reason to want to decrease it. (This is somewhat oversimplified, because it ignores the contribution of the Federal Reserve, interest rates, and bank-created money. Most of the money in the world is actually not created by the government, but by banks which are restrained to greater or lesser extent by the government.)

Even a lot of people who try to explain modern monetary theory mistakenly speak as though there was a fundamental shift when we fully abandoned the gold standard in the 1970s. (This is a good explanation overall, but it makes this very error.) But in fact a gold standard really isn’t money “backed” by anything—gold is not what gives the money value, gold is almost worthless by itself. It’s pretty and it doesn’t corrode, but otherwise, what exactly can you do with it? Being tied to money is what made gold valuable, not the other way around. To see this, imagine a world where you have 20,000 tons of gold, but you know that you can never sell it. No one will ever purchase a single ounce. Would you feel particularly rich in that scenario? I think not. Now suppose you have a virtually limitless quantity of pieces of paper that you know people will accept for anything you would ever wish to buy. They are backed by nothing, they are just pieces of paper—but you are now rich, by the standard definition of the word. I can even make the analogy remove the exchange value of money and just use taxation: if you know that in two days you will be imprisoned if you don’t have this particular piece of paper, for the next two days you will guard that piece of paper with your life. It won’t bother you that you can’t exchange that piece of paper for anything else—you wouldn’t even want to. If instead someone else has it, you’ll be willing to do some rather large favors for them in order to get it.

Whenever people try to tell me that our money is “worthless” because it’s based on fiat instead of backed by gold (this happens surprisingly often), I always make them an offer: If you truly believe that our money is worthless, I’ll gladly take any you have off of your hands. I will even provide you with something of real value in return, such as an empty aluminum can or a pair of socks. If they truly believe that fiat money is worthless, they should eagerly accept my offer—yet oddly, nobody ever does.

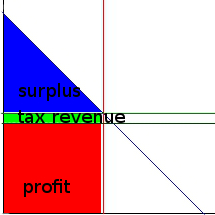

This does actually create a rather interesting argument against progressive taxation: If the goal of taxation is simply to control inflation, shouldn’t we tax people based only on their spending? Well, if that were the only goal, maybe. But we also have other goals, such as maintaining employment and controlling inequality. Progressive taxation may actually take a larger amount of money out of the system than would be necessary simply to control inflation; but it does so in order to ensure that the super-rich do not become even more rich and powerful.

Governments are limited by real constraints of power and resources, but they they have no monetary constraints other than those they impose themselves. There is definitely something strongly coercive about taxation, and therefore about a monetary system which is built upon taxation. Unfortunately, I don’t know of any good alternatives. We might be able to come up with one: Perhaps people could donate to public goods in a mutually-enforced way similar to Kickstarter, but nobody has yet made that practical; or maybe the government could restructure itself to make a profit by selling private goods at the same time as it provides public goods, but then we have all the downsides of nationalized businesses. For the time being, the only system which has been shown to work to provide public goods and maintain long-term monetary stability is a system in which the government taxes and spends.

A gold standard is just a fiat monetary system in which the central bank arbitrarily decides that their money supply will be directly linked to the supply of an arbitrarily chosen commodity. At best, this could be some sort of commitment strategy to ensure that they don’t create vastly too much or too little money; but at worst, it prevents them from actually creating the right amount of money—and the gold standard was basically what caused the Great Depression. A gold standard is no more sensible a means of backing your currency than would be a standard requiring only prime-numbered interest rates, or one which requires you to print exactly as much money per minute as the price of a Ferrari.

No, the real thing that backs our money is the existence of the tax system. Far from taxation being “taking your hard-earned money”, without taxes money itself could not exist.