JDN 2457215 EDT 15:43.

One of the most basic questions in macroeconomics has oddly enough received very little attention: How much should we save? What is the optimal level of saving?

At the microeconomic level, how much you should save basically depends on what you think your income will be in the future. If you have more income now than you think you’ll have later, you should save now to spend later. If you have less income now than you think you’ll have later, you should spend now and dissave—save negatively, otherwise known as borrowing—and pay it back later. The life-cycle hypothesis says that people save when they are young in order to retire when they are old—in its strongest form, it says that we keep our level of spending constant across our lifetime at a value equal to our average income. The strongest form is utterly ridiculous and disproven by even the most basic empirical evidence, so usually the hypothesis is studied in a weaker form that basically just says that people save when they are young and spend when they are old—and even that runs into some serious problems.

The biggest problem, I think, is that the interest rate you receive on savings is always vastly less than the interest rate you pay on borrowing, which in turn is related to the fact that people are credit-constrained—they generally would like to borrow more than they actually can. It also has a lot to do with the fact that our financial system is an oligopoly; banks make more profits if they can pay savers less and charge borrowers more, and by colluding with each other they can control enough of the market that no major competitors can seriously undercut them. (There is some competition, however, particularly from credit unions—and if you compare these two credit card offers from University of Michigan Credit Union at 8.99%/12.99% and Bank of America at 12.99%/22.99% respectively, you can see the oligopoly in action as the tiny competitor charges you a much fairer price than the oligopoly beast. 9% means doubling in just under eight years, 13% means doubling in a little over five years, and 23% means doubling in three years.) Another very big problem with the life-cycle theory is that human beings are astonishingly bad at predicting the future, and thus our expectations about our future income can vary wildly from the actual future income we end up receiving. People who are wise enough to know that they do not know generally save more than they think they’ll need, which is called precautionary saving. Combine that with our limited capacity for self-control, and I’m honestly not sure the life-cycle hypothesis is doing any work for us at all.

But okay, let’s suppose we had a theory of optimal individual saving. That would still leave open a much larger question, namely optimal aggregate saving. The amount of saving that is best for each individual may not be best for society as a whole, and it becomes a difficult policy challenge to provide incentives to make people save the amount that is best for society.

Or it would be, if we had the faintest idea what the optimal amount of saving for society is. There’s a very simple rule-of-thumb that a lot of economists use, often called the golden rule (not to be confused with the actual Golden Rule, though I guess the idea is that a social optimum is a moral optimum), which is that we should save exactly the same amount as the share of capital in income. If capital receives one third of income (This figure of one third has been called a “law”, but as with most “laws” in economics it’s really more like the Pirate Code; labor’s share of income varies across countries and years. I doubt you’ll be surprised to learn that it is falling around the world, meaning more income is going to capital owners and less is going to workers.), then one third of income should be saved to make more capital for next year.

When you hear that, you should be thinking: “Wait. Saved to make more capital? You mean invested to make more capital.” And this is the great sleight of hand in the neoclassical theory of economic growth: Saving and investment are made to be the same by definition. It’s called the savings-investment identity. As I talked about in an earlier post, the model seems to be that there is only one kind of good in the world, and you either use it up or save it to make more.

But of course that’s not actually how the world works; there are different kinds of goods, and if people stop buying tennis shoes that doesn’t automatically lead to more factories built to make tennis shoes—indeed, quite the opposite.If people reduce their spending, the products they no longer buy will now accumulate on shelves and the businesses that make those products will start downsizing their production. If people increase their spending, the products they now buy will fly off the shelves and the businesses that make them will expand their production to keep up.

In order to make the savings-investment identity true by definition, the definition of investment has to be changed. Inventory accumulation, products building up on shelves, is counted as “investment” when of course it is nothing of the sort. Inventory accumulation is a bad sign for an economy; indeed the time when we see the most inventory accumulation is right at the beginning of a recession.

As a result of this bizarre definition of “investment” and its equation with saving, we get the famous Paradox of Thrift, which does indeed sound paradoxical in its usual formulation: “A global increase in marginal propensity to save can result in a reduction in aggregate saving.” But if you strip out the jargon, it makes a lot more sense: “If people suddenly stop spending money, companies will stop investing, and the economy will grind to a halt.” There’s still a bit of feeling of paradox from the fact that we tried to save more money and ended up with less money, but that isn’t too hard to understand once you consider that if everyone else stops spending, where are you going to get your money from?

So what if something like this happens, we all try to save more and end up having no money? The government could print a bunch of money and give it to people to spend, and then we’d have money, right? Right. Exactly right, in fact. You now understand monetary policy better than most policymakers. Like a basic income, for many people it seems too simple to be true; but in a nutshell, that is Keynesian monetary policy. When spending falls and the economy slows down as a result, the government should respond by expanding the money supply so that people start spending again. In practice they usually expand the money supply by a really bizarre roundabout way, buying and selling bonds in open market operations in order to change the interest rate that banks charge each other for loans of reserves, the Fed funds rate, in the hopes that banks will change their actual lending interest rates and more people will be able to borrow, thus, ultimately, increasing the money supply (because, remember, banks don’t have the money they lend you—they create it).

We could actually just print some money and give it to people (or rather, change a bunch of numbers in an IRS database), but this is very unpopular, particularly among people like Ron Paul and other gold-bug Republicans who don’t understand how monetary policy works. So instead we try to obscure the printing of money behind a bizarre chain of activities, opening many more opportunities for failure: Chiefly, we can hit the zero lower bound where interest rates are zero and can’t go any lower (or can they?), or banks can be too stingy and decide not to lend, or people can be too risk-averse and decide not to borrow; and that’s not even to mention the redistribution of wealth that happens when all the money you print is given to banks. When that happens we turn to “unconventional monetary policy”, which basically just means that we get a little bit more honest about the fact that we’re printing money. (Even then you get articles like this one insisting that quantitative easing isn’t really printing money.)

I don’t know, maybe there’s actually some legitimate reason to do it this way—I do have to admit that when governments start openly printing money it often doesn’t end well. But really the question is why you’re printing money, whom you’re giving it to, and above all how much you are printing. Weimar Germany printed money to pay off odious war debts (because it totally makes sense to force a newly-established democratic government to pay the debts incurred by belligerent actions of the monarchy they replaced; surely one must repay one’s debts). Hungary printed money to pay for rebuilding after the devastation of World War 2. Zimbabwe printed money to pay for a war (I’m sensing a pattern here) and compensate for failed land reform policies. In all three cases the amount of money they printed was literally billions of times their original money supply. Yes, billions. They found their inflation cascading out of control and instead of stopping the printing, they printed even more. The United States has so far printed only about three times our original monetary base, still only about a third of our total money supply. (Monetary base is the part that the Federal reserve controls; the rest is created by banks. Typically 90% of our money is not monetary base.) Moreover, we did it for the right reasons—in response to deflation and depression. That is why, as Matthew O’Brien of The Atlantic put it so well, the US can never be Weimar.

I was supposed to be talking about saving and investment; why am I talking about money supply? Because investment is driven by the money supply. It’s not driven by saving, it’s driven by lending.

Now, part of the underlying theory was that lending and saving are supposed to be tied together, with money lent coming out of money saved; this is true if you assume that things are in a nice tidy equilibrium. But we never are, and frankly I’m not sure we’d want to be. In order to reach that equilibrium, we’d either need to have full-reserve banking, or banks would have to otherwise have their lending constrained by insufficient reserves; either way, we’d need to have a constant money supply. Any dollar that could be lent, would have to be lent, and the whole debt market would have to be entirely constrained by the availability of savings. You wouldn’t get denied for a loan because your credit rating is too low; you’d get denied for a loan because the bank would literally not have enough money available to lend you. Banking would have to be perfectly competitive, so if one bank can’t do it, no bank can. Interest rates would have to precisely match the supply and demand of money in the same way that prices are supposed to precisely match the supply and demand of products (and I think we all know how well that works out). This is why it’s such a big problem that most macroeconomic models literally do not include a financial sector. They simply assume that the financial sector is operating at such perfect efficiency that money in equals money out always and everywhere.

So, recognizing that saving and investment are in fact not equal, we now have two separate questions: What is the optimal rate of saving, and what is the optimal rate of investment? For saving, I think the question is almost meaningless; individuals should save according to their future income (since they’re so bad at predicting it, we might want to encourage people to save extra, as in programs like Save More Tomorrow), but the aggregate level of saving isn’t an important question. The important question is the aggregate level of investment, and for that, I think there are two ways of looking at it.

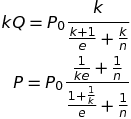

The first way is to go back to that original neoclassical growth model and realize it makes a lot more sense when the s term we called “saving” actually is a funny way of writing “investment”; in that case, perhaps we should indeed invest the same proportion of income as the income that goes to capital. An interesting, if draconian, way to do so would be to actually require this—all and only capital income may be used for business investment. Labor income must be used for other things, and capital income can’t be used for anything else. The days of yachts bought on stock options would be over forever—though so would the days of striking it rich by putting your paycheck into a tech stock. Due to the extreme restrictions on individual freedom, I don’t think we should actually do such a thing; but it’s an interesting thought that might lead to an actual policy worth considering.

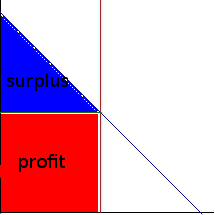

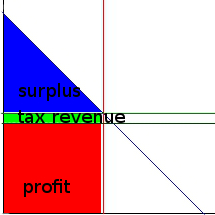

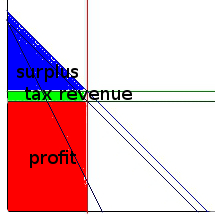

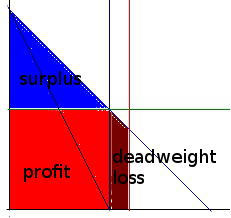

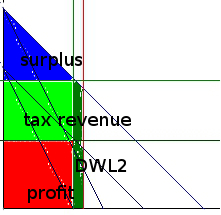

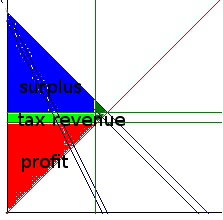

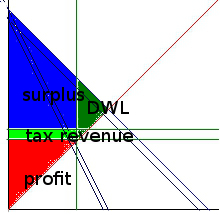

But a second way that might actually be better—since even though the model makes more sense this way, it still has a number of serious flaws—is to think about what we might actually do in order to increase or decrease investment, and then consider the costs and benefits of each of those policies. The simplest case to analyze is if the government invests directly—and since the most important investments like infrastructure, education, and basic research are usually done this way, it’s definitely a useful example. How is the government going to fund this investment in, say, a nuclear fusion project? They have four basic ways: Cut spending somewhere else, raise taxes, print money, or issue debt. If you cut spending, the question is whether the spending you cut is more or less important than the investment you’re making. If you raise taxes, the question is whether the harm done by the tax (which is generally of two flavors; first there’s the direct effect of taking someone’s money so they can’t use it now, and second there’s the distortions created in the market that may make it less efficient) is outweighed by the new project. If you print money or issue debt, it’s a subtler question, since you are no longer pulling from any individual person or project but rather from the economy as a whole. Actually, if your economy has unused capacity as in a depression, you aren’t pulling from anywhere—you’re simply adding new value basically from thin air, which is why deficit spending in depressions is such a good idea. (More precisely, you’re putting resources to use that were otherwise going to lay fallow—to go back to my earlier example, the tennis shoes will no longer rest on the shelves.) But if you do not have sufficient unused capacity, you will get crowding-out; new debt will raise interest rates and make other investments more expensive, while printing money will cause inflation and make everything more expensive. So you need to weigh that cost against the benefit of your new investment and decide whether it’s worth it.

This second way is of course a lot more complicated, a lot messier, a lot more controversial. It would be a lot easier if we could just say: “The target investment rate should be 33% of GDP.” But even then the question would remain as to which investments to fund, and which consumption to pull from. The abstraction of simply dividing the economy into “consumption” versus “investment” leaves out matters of the utmost importance; Paul Allen’s 400-foot yacht and food stamps for children are both “consumption”, but taxing the former to pay for the latter seems not only justified but outright obligatory. The Bridge to Nowhere and the Humane Genome Project are both “investment”, but I think we all know which one had a higher return for human society. The neoclassical model basically assumes that the optimal choices for consumption and investment are decided automatically (automagically?) by the inscrutable churnings of the free market, but clearly that simply isn’t true.

In fact, it’s not always clear what exactly constitutes “consumption” versus “investment”, and the particulars of answering that question may distract us from answering the questions that actually matter. Is a refrigerator investment because it’s a machine you buy that sticks around and does useful things for you? Or is it consumption because consumers buy it and you use it for food? Is a car an investment because it’s vital to getting a job? Or is it consumption because you enjoy driving it? Someone could probably argue that the appreciation on Paul Allen’s yacht makes it an investment, for instance. Feeding children really is an investment, in their so-called “human capital” that will make them more productive for the rest of their lives. Part of the money that went to the Humane Genome Project surely paid some graduate student who then spent part of his paycheck on a keg of beer, which would make it consumption. And so on. The important question really isn’t “is this consumption or investment?” but “Is this worth doing?” And thus, the best answer to the question, “How much should we save?” may be: “Who cares?”