JDN 2457489

(The topic of this post was chosen by a vote of my Patreons.) There seem to be two major camps on most political issues: One camp says “This is not a problem, stop worrying about it.” The other says “This is a huge problem, it must be fixed right away, and here’s the easy solution.” Typically neither of these things is true, and the correct answer is actually “This is a huge problem, well worth fixing—but we need to do a lot of work to figure out exactly how.”

Sweatshop labor is a very good example of this phenomenon.

Camp A is represented here by the American Enterprise Institute, which even goes as far as to defend child labor on the grounds that “we used to do it before”. (Note that we also used to do slavery before. Also protectionism, but of course AEI doesn’t think that was good. Who needs logical consistency when you have ideological purity?) The College Conservative uses ECON 101 to defend sweatshops, perhaps not realizing that economics courses continue past ECON 101.

Camp B is represented here by Buycott, telling us to buy “made in the USA” products and boycott all companies that use sweatshops. Other commonly listed strategies include buying used clothes (I mean, there may be some ecological benefits to this, but clearly not all clothes can be used clothes) and “buy union-made” which is next to impossible for most products. Also in this camp is LaborVoices, a Silicon Valley tech company that seems convinced they can somehow solve the problem of sweatshops by means of smartphone apps, because apparently Silicon Valley people believe that smartphones are magical and not, say, one type of product that performs services similar to many other pre-existing products but somewhat more efficiently. (This would also explain how Uber can say with a straight face that they are “revolutionary” when all they actually do is mediate unlicensed taxi services, and Airbnb is “innovative” because it makes it slightly more convenient to rent out rooms in your home.)

Of course I am in that third camp, people who realize that sweatshops—and exploitative labor practices in general—are a serious problem, but a very complex and challenging one that does not have any easy, obvious solutions.

One thing we absolutely cannot do is return to protectionism or get American consumers to only buy from American companies (a sort of “soft protectionism” by social construction). This would not only be inefficient for us—it would be devastating for people in Third World countries. Sweatshops typically provide substantially better living conditions than the alternatives available to their workers.

Yet this does not mean that sweatshops are morally acceptable or should simply be left alone, contrary to the assertions of many economists—most famously Benjamin Powell. Anyone who doubts this must immediately read “Wrongful Beneficence” by Chris Meyers; the mere fact that an act benefits someone –or even everyone—does not prove that the act was morally acceptable. If someone is starving to death and you offer them bread in exchange for doing whatever you want them to do for the next year, you are benefiting them, surely—but what you are doing is morally wrong. And this is basically what sweatshops are; they provide survival in exchange for exploitation.

It can be remarkably difficult to even tell which companies are using sweatshops—and this is by design. While in response to public pressure corporations often try to create the image of improving their labor standards, they seem quite averse to actually improving labor standards, and even more averse to establishing systems of enforcement to make those labor standards followed consistently. Almost no sweatshops are directly owned by the retailers whose products they make; instead there is a chain of outsourced vendors and distributors, a chain that creates diffusion of responsibility and plausible deniability. When international labor organizations do get the chance to investigate the labor conditions of factories operated by multinational corporations, they invariably find that regulations are more honored in the breach than the observance.

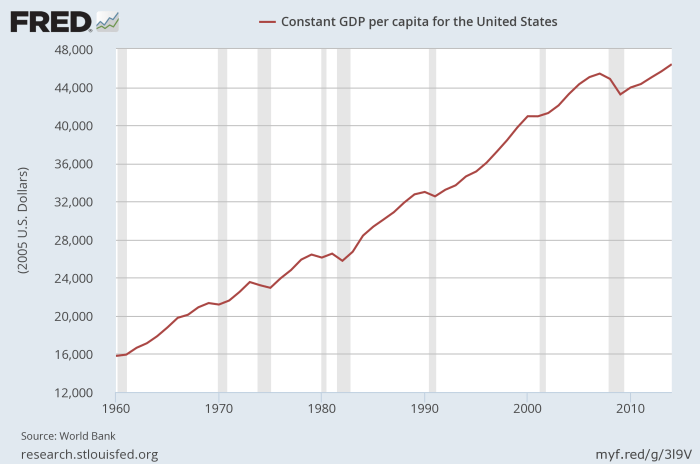

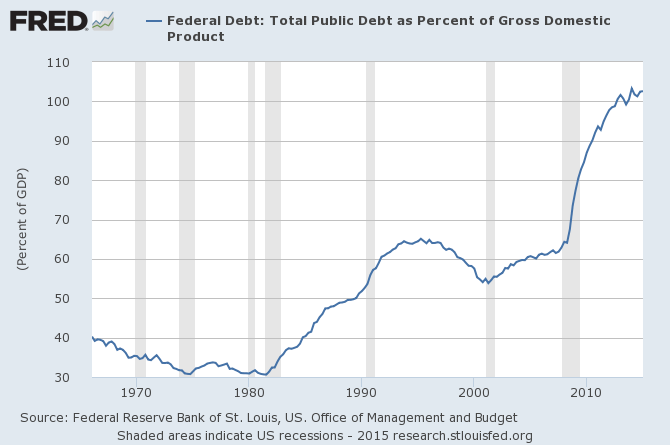

So, what would a long-run solution to sweatshops look like? In a word: Development. The only sustainable solution to oppressive labor conditions is a world where everyone is healthy enough, educated enough, and provided with enough resources that their productivity is at a First World level; furthermore it is a world where workers have enough bargaining power that they are actually paid according to that productivity. (The US has lately been finding out what happens if you do the former but not the latter—the result is that you generate an enormous amount of wealth, but it all ends up in the hands of the top 0.1%. Yet it is quite possible to do the latter, as Denmark has figured out, #ScandinaviaIsBetter.)

To achieve this, we need more factories in Third World countries, not fewer—more investment, not less. We need to buy more of China’s exports, hire more factory workers in Bangladesh.

But it’s not enough to provide incentives to build factories—we must also provide incentives to give workers at those factories more bargaining power.

To see how we can pull this off, I offer a case study of a (qualified) success: Nike.

In the 1990s, Nike’s subcontractors had some of the worst labor conditions in the shoe industry. Today, they actually have some of the best. How did that happen?

It began with people noticing a problem—activists and investigative journalists documented the abuses in Nike’s factories. They drew public attention, which undermined Nike’s efforts at mass advertising (which was basically their entire business model—their shoes aren’t actually especially good). They tried to clean up their image with obviously biased reports, which triggered a backlash. Finally Nike decides to actually do something about the problem, and actually becomes a founding member of the Fair Labor Association. They establish new labor standards, and they audit regularly to ensure that those standards are being complied with. Today they publish an annual corporate social responsibility report that actually appears to be quite transparent and accurate, showing both the substantial improvements that have been made and the remaining problems. Activist campaigns turned Nike around almost completely.

In short, consumer pressure led to private regulation. Many development economists are increasingly convinced that this is what we need—we must put pressure on corporations to regulate themselves.

The pressure is a key part of this process; Willem Buiter wasn’t wrong when he quipped that “self-regulation stands in relation to regulation the way self-importance stands in relation to importance and self-righteousness to righteousness.” For any regulation to work, it must have an enforcement mechanism; for private regulation to work, that enforcement mechanism comes from the consumers.

Yet even this is not enough, because there are too many incentives for corporations to lie and cheat if they only have to be responsive to consumers. It’s unreasonable to expect every consumer to take the time—let alone have the expertise—to perform extensive research on the supply chain of every corporation they buy a product from. I also think it’s unreasonable to expect most people to engage in community organizing or shareholder activism as Green America suggests, though it certainly wouldn’t hurt if some did. But there are just too many corporations to keep track of! Like it or not, we live in a globalized capitalist economy where you almost certainly buy from a hundred different corporations over the course of a year.

Instead we need governments to step up—and the obvious choice is the government of the United States, which remains the world’s economic and military hegemon. We should be pressuring our legislators to make new regulations on international trade that will raise labor standards around the globe.

Note that this undermines the most basic argument corporations use against improving their labor standards: “If we raise wages, we won’t be able to compete.” Not if we force everyone to raise wages, around the globe. “If it’s cheaper to build a factory in Indonesia, why shouldn’t we?” It won’t be cheaper, unless Indonesia actually has a real comparative advantage in producing that product. You won’t be able to artificially hold down your expenses by exploiting your workers—you’ll have to actually be more efficient in order to be more profitable, which is how capitalism is supposed to work.

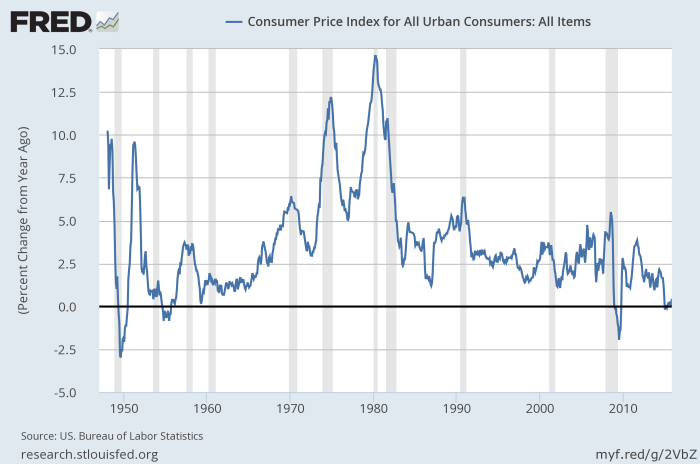

There’s another argument we often hear that is more legitimate, which is that raising wages would also force corporations to raise prices. But as I discussed in a previous post on this subject, the amount by which prices would need to rise is remarkably small, and nowhere near large enough to justify panic about dangerous global inflation. Paying 10% or even 20% more for our products is well worth it to reduce the corruption and exploitation that abuses millions of people—a remarkable number of them children—around the globe. Also, it doesn’t take a mathematical savant to realize that if increasing wages by a factor of 10 only increases prices by 20%, workers will in fact be better off.

Where would all that extra money come from? Now we come to the real reason why corporations don’t want to raise their labor standards: It would come from profits. Right now profits are extraordinarily large, much larger than they have any right to be in a fair market. It was recently estimated that 74% of billionaire wealth comes from economic rent—that is to say, from deception, exploitation, and market manipulation, rather than actual productivity. (There’s a lot of uncertainty in this estimate; the true figure is probably somewhere between 50% and 90%—it’s almost certainly a majority, and could be the vast majority.) In fact, I really shouldn’t say “money”, which we can just print; what we really want to know is where the extra wealth would come from to give that money value. But by paying workers more, improving their standard of living, and creating more consumer demand, we would in fact dramatically increase the amount of real wealth in the world.

So, we need regulations to improve global labor standards. But we must first be clear: What should these regulations say?

First, we must rule out protectionist regulations that would give unfair advantages to companies that produce locally. These would only result in economic inefficiency at best, and trade wars throwing millions back into poverty at worst. (Some advantage makes sense to internalize the externalities of shipping, but really that should be created by a carbon tax, not by trade tariffs. It’s a lot more expensive and carbon-intensive to ship from Detroit to LA than from Detroit to Windsor, but the latter is the “international” trade.)

Second, we should not naively assume that every country should have the same minimum wage. (I am similarly skeptical of Hillary Clinton’s proposal to include people with severe mental or physical disabilities in the US federal minimum wage; I too am concerned about people with disabilities being exploited, but the fact is many people with severe disabilities really aren’t as productive, and it makes sense for wages to reflect that.) If we’re going to have minimum wages at all—basic income and wage subsidies both make a good deal more sense than a hard price floor; see also my earlier post on minimum wage—they should reflect the productivity and prices of the region. I applaud California and New York for adopting $15 minimum wages, but I’d be a bit skeptical of doing the same in Mississippi, and adamantly opposed to doing so in Bangladesh.

It may not even be reasonable to expect all countries to have the same safety standards; workers who are less skilled and in more dire poverty may rationally be willing to accept more risk to remain employed, rather than laid off because their employer could not afford to meet safety standards and still pay them a sufficient wage. For some safety standards this is ridiculous; making sufficiently many exits with doors that swing outward and maintaining smoke detectors are not expensive things to do. (And yet factories in Bangladesh often fail to meet such basic requirements, which kills hundreds of workers each year.) But other safety standards may be justifiably relaxed; OSHA compliance in the US costs about $70 billion per year, about $200 per person, which many countries simply couldn’t afford. (On the other hand, OSHA saves thousands of lives, does not increase unemployment, and may actually benefit employers when compared with the high cost of private injury lawsuits.) We should have expert economists perform careful cost-benefit analyses of proposed safety regulations to determine which ones are cost-effective at protecting workers and which ones are too expensive to be viable.

While we’re at it, these regulations should include environmental standards, or a global carbon tax that’s used to fund climate change mitigation efforts around the world. Here there isn’t much excuse for not being strict; pollution and environmental degradation harms the poor the most. Yes, we do need to consider the benefits of production that is polluting; but we have plenty of profit incentives for that already. Right now the balance is clearly tipped far too much in favor of more pollution than the optimum rather than less. Even relatively heavy-handed policies like total bans on offshore drilling and mountaintop removal might be in order; in general I’d prefer to tax rather than ban, but these activities are so enormously damaging that if the choice is between a ban and doing nothing, I’ll take the ban. (I’m less convinced of this with regard to fracking; yes, earthquakes and polluted groundwater are bad—but are they Saudi Arabia bad? Because buying more oil from Saudi Arabia is our leading alternative.)

It should go without saying (but unfortunately it doesn’t seem to) that our regulations must include an absolute zero-tolerance policy for forced labor. If we find out that a company is employing forced labor, they should have to not only free every single enslaved worker, but pay each one a million dollars (PPP 2005 chained CPI of course). If they can’t do that and they go bankrupt, good riddance; remind me to play them the world’s saddest song on the world’s tiniest violin. Of course, first we need to find out, which brings me to the most important point.

Above all, these regulations must be enforced. We could start with enforceable multilateral trade agreements, where tariff reductions are tied to human rights and labor standards. This is something the President of the United States could do, right now, as an addendum to the Trans-Pacific Partnership. (What he should have done is made the TPP contingent on this, but it’s too late for that.) Future trade agreements should include these as a matter of course.If countries want to reap the benefits of free trade, they must be held accountable for sharing those benefits equitably with their people.

But ultimately we should not depend upon multilateral agreements between nations—we need truly international standards with global enforcement. We should empower the International Labor Organization to enact sanctions and inspections (right now it mostly enacts suggestions which are promptly and dutifully ignored), and possibly even to arrest executives for trial at the International Criminal Court. We should double if not triple or quadruple their funding—and if member nations will not pay this voluntarily, we should make them—the United Nations should be empowered to collect taxes in support of global development, which should be progressive with per-capita GDP. Coercion, you say? National sovereignty, you say? Millions of starving little girls is my reply.

Right now, the ability of multinational corporations to move between countries to find the ones that let them pay the least have created a race to the floor; it’s time for us to raise that floor.

What can you yourself do, assuming you’re not a head of state? (If you are, I’m honored. Also, any openings on your staff?) Well, you can vote—and you can use that vote to put pressure on your legislators to support these kinds of polices. There are also some other direct actions you can take that I discussed in a previous post; but mainly what we need is policy. Consumer pressure and philanthropy are good, and by all means, don’t stop; but to really achieve global justice we will need nothing short of global governance.